“I want these bands to be considered as a part of the big musical export and mentioned in the same breath as ABBA,” David Andersson tells me with a passion bordering on anger. He is talking about 1980s Swedish Råpunk (raw punk), a genre with an aggressive sound that could not be further from those purveyors of perfect Swedish pop.

Andersson, however, remains unbowed, saying of his Råpunk: The Birth of Swedish Hardcore, 1981-89 (No Good), the first publication to document this forgotten subculture, “I hope my book actually helps them to achieve that kind of status.”

Today, Andersson cuts an unassuming figure as a flannel shirt-clad PhD student at Linköping University. But 35 years ago he was a scruffy pre-teenage punk immersed in a movement of radicals who not only wanted to change music, but the world.

Andersson spent two years travelling around Sweden tracking down the evocative photographs and ephemera that make up Råpunk. “I felt like I was travelling in time, in a way,” he says. “That’s always been my biggest dream since I was a kid.”

In returning to his youth, he also takes the reader back to an era when Sweden was home to one of Europe’s most extreme subcultures, which was a unique product of the social conditions of its time.

“Boredom was a very, very important factor,” Andersson says plainly when asked about the birth of Råpunk. For the young in 1980s Sweden, he says, “there was this complete sense of boredom that you had absolutely no control over.”

While the postwar economic boom and the earlier espousal of the concept of Folkhemmet (the people’s home) by the Swedish prime minister of the 1930s and 40s, Per Albin Hansson, had led to the development of perhaps the most muscular welfare state in the world, Andersson makes the case that “what tranquillity is to some is crushing boredom to others”.

Some Swedish youth, he tells me, began to baulk at the idea that “your life has been decided for you by the welfare state in order for you not to starve to death”.

Andersson was shaken out of his own personal ennui when he was just 12 and living in a declining industrial town an hour outside of Linköping, when the Sex Pistols’ Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle was shown on TV. “It was kind of like an epiphany when I heard that there’s this different way of expressing yourself,” he says. “It was pure in its expression – there was no filter. It was raw emotion and that touched me.”

Soon, he was off in search of his punk kin. “I was the only punk in the village, so to speak,” Andersson says, describing a provincial masculine culture that revolved solely around football and heavy metal. “I had to get out physically to another place to find people who were like-minded.”

He moved to Linköping aged just 15 and became the frontman of a local Råpunk band, Identity. By that time the Råpunk scene was in full swing, its sounds the result of cultural cross-pollination across borders some years earlier.

The anarcho-punk of Epping’s Crass and Stoke-on-Trent’s Discharge, as well as the pioneering hardcore of San Francisco’s Dead Kennedys, were Råpunk’s formative influences, and their literally visceral visuals – cut-and-pasted grainy reportage photography of famine, violence and the horrors of war – were also widely adopted by these Swedish acts.

Yet Råpunk had a unique energy all of its own. Bands like Anti Cimex, Mob 47 and Skitslickers (translation: Shitlickers) had a distinctively angry charge to their music that still burns white-hot today.

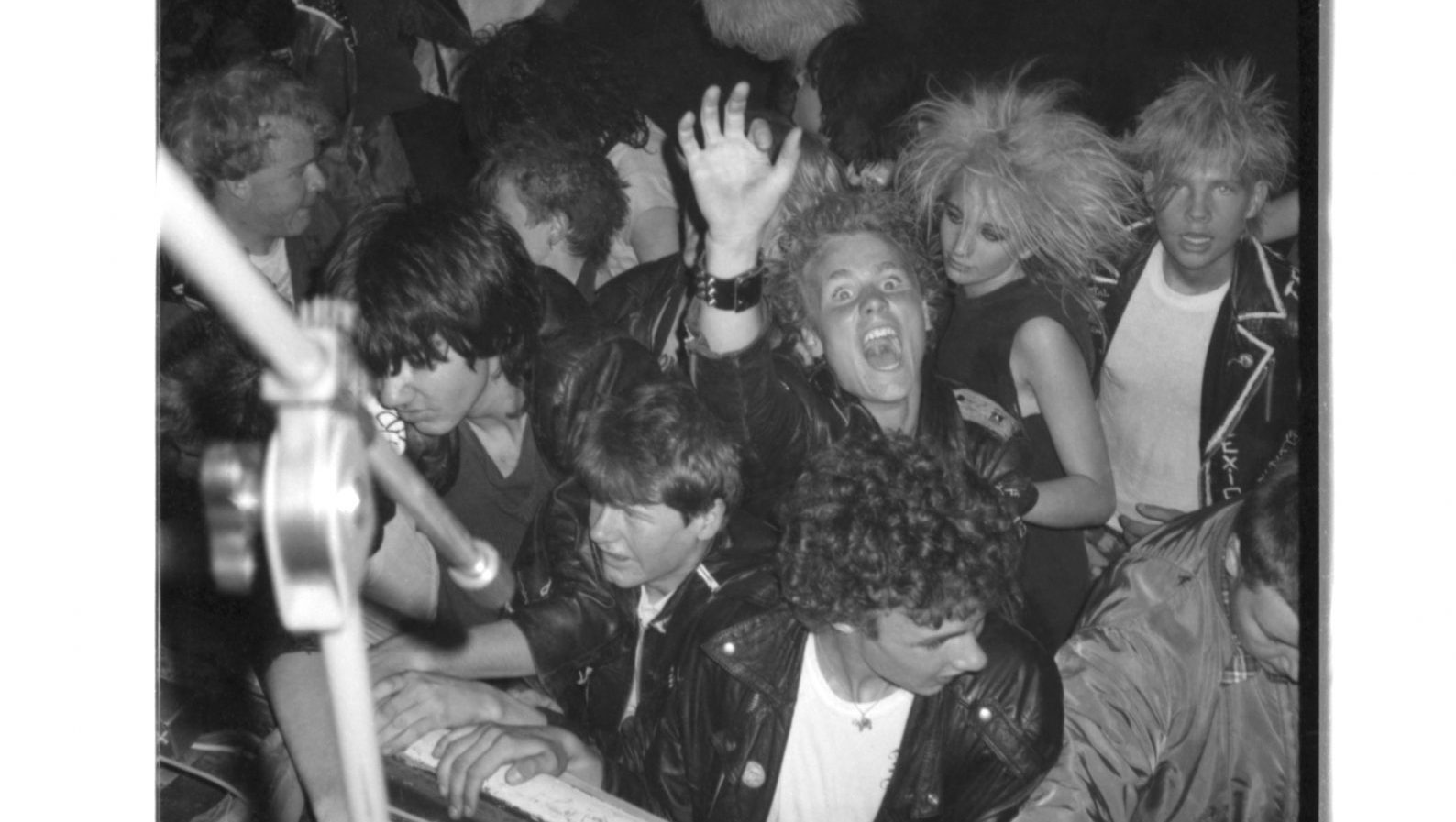

The Skitslickers’ eponymous 1982 debut EP was Råpunk’s seminal moment, with four breakneck tracks that were a wall of distortion and screamed vocals, and a cover photo showing a soldier about to stick a bayonet into the stomach of a PoW. That Skitslickers vocalist Skit Lasse’s on-stage antics were the stuff of legend, taping the microphone to his hand and “interacting” with the crowd violently, underlined that Råpunk was also a scene rooted in electrifying live performance.

Andersson’s book argues that a unique mix of factors beyond plain boredom fed Råpunk’s energy. The individualist, anti-fascist politics of their Anglophone forebears – an ideology that left the nihilistic “destroy” message of the first wave of punk far behind – gave Råpunk its political blueprint, and the threat of the cold war turning nuclear-hot was also formative. But there were uniquely Swedish issues that fundamentally shaped Råpunk.

By the 1980s, the Swedish social democratic dream had become tarnished, and not just for the young. As manufacturing nosedived, impacting jobs, and the utopian vision of the Miljonprogrammet – which had built a million homes in 10 years – turned sour, working-class communities were left languishing in declining mill towns, like Andersson’s own, or ghettoised in brutalist estates. An already disaffected youth were, in some cases, radicalised.

While some turned to the neo-Nazi Nordiska rikspartiet (NRP) and Bevara Sverige Svenskt (Keep Sweden Swedish) (“There were quite a lot of skinheads in Linköping,” Andersson says, ominously), Råpunks adopted anarchist principles. This was in flagrant disregard of the unspoken assumption at the heart of the Folkhemmet – “You can’t have people that don’t play ball,” Andersson says.

For some, Råpunk identity meant participation in political direct action, from the Husnallarna movement, which squatted buildings targeted for redevelopment in Gothenburg’s historic Haga neighbourhood (their slogan – “Yuppie scum out of Haga”), to the vandalisation of Shell petrol stations (Shell was accused of evading the apartheid oil embargo).

But in fact politics was stitched into the very fabric of what Andersson calls Råpunk’s “creative ecology” – a self-starting, democratic and completely non-commercial network whose music was self-made and self-distributed, and where principles of autonomy and equality were foundational.

DIY fanzines – dubbed “zines” in the spirit of fans and bands sharing equal status – were key to Råpunk’s information-sharing networks, and Andersson had founded his own zine, Bubbel-Bad (Bubble Bath), soon after his Sex Pistols epiphany.

Råpunk zines were also shared internationally, as avid letter-writing sustained links with overseas punk scenes (postage costs were mitigated by the devious method of putting soap or glue over stamps to protect them from the postmark so they could be reused). InterRail passes were exploited to their full potential over their month-long validity to travel to meet fellow punks across Europe, go to gigs and crash at squats.

But since principles of self-sufficiency were at the very heart of Råpunk, it was somewhat ironic that the scene in fact often depended on the apparatus of a state that it professed to despise. The Ny Våg (New Wave) radio show on the Swedish national broadcaster was a major source of dissemination of Råpunk music, and its presenter, Jonas Almquist of the Gothenburg band Lädernunnan (Leather Nun), was a bona fide member of the scene. It has been suggested that the very phrase “raw punk” was coined on this state-run programme.

Grants for arts projects were also exploited by Råpunk bands, who would start up a legitimate-sounding studiecirkel (workshop) and get funding they would use to rent rehearsal spaces or even put a record out.

With rock venues thin on the ground, Råpunk bands improvised by putting on typically chaotic, beer-soaked gigs at the local Folkets hus (people’s house – something akin to a working men’s club), Arbetarnas bildningsförbund (Workers’ Educational Association) halls, or even under the auspices of the IOGT-NTO Swedish temperance society.

The most famous Råpunk venue of all, Ultra, was a house in the wooded Stockholm suburbs belonging to a city-sponsored cultural association. Famous enough to attract international acts to its 50-person capacity living-room “auditorium”, including American hardcore legends Black Flag and the Washington band Scream (featuring a teenage Dave Grohl on drums), Ultra summed up the strange paradoxes and specifically Swedish flavour of Råpunk – it was a graffiti-covered punk squat that was publicly funded and where the homemade cinnamon rolls were apparently legendary.

But for all its Swedishness, Råpunk’s legacy is a surprisingly international one. Andersson’s inspiration for the book came from his years travelling the world as part of London-based dance music duo Punks Jump Up, when he was astonished to see kids in places as far-flung as Singapore, Australia, Chile, Mexico and the US with Råpunk band patches on their clothes. “They were the bands that I was into in the 1980s – the ones that released a record in only 500 copies,” he says. “It blew my mind.”

He adds: “In the favelas of São Paulo in Brazil, the same acts are massive. They’re big as a part of the counterculture.”

Råpunk’s reach is further proven by Helvetet records of Lima, Peru, making a specialism of the genre, while a small scene of Japanese bands are so inspired by Råpunk that they not only have Swedish names but in some cases actually sing in Swedish.

“I don’t ask the Råpunks to accept the ‘fine culture’ role, but I want the cultural elite to respect them,” Andersson tells me, again with barely concealed ire, and he remains steadfast in his aim of giving Råpunk its rightful place in Swedish history.

But he also points out the contemporary relevance of Råpunk. “Punk has many levels,” he says. “It’s pure rage, but it’s also thought and ideology and not just sitting around and accepting things.”

Andersson mentions the Gaza protests and climate activism – “It’s the same kind of rage and it’s the same kind of desperation.”

In a world facing problems on every shore, Råpunk’s pure rage will always be a language that doesn’t need translating.