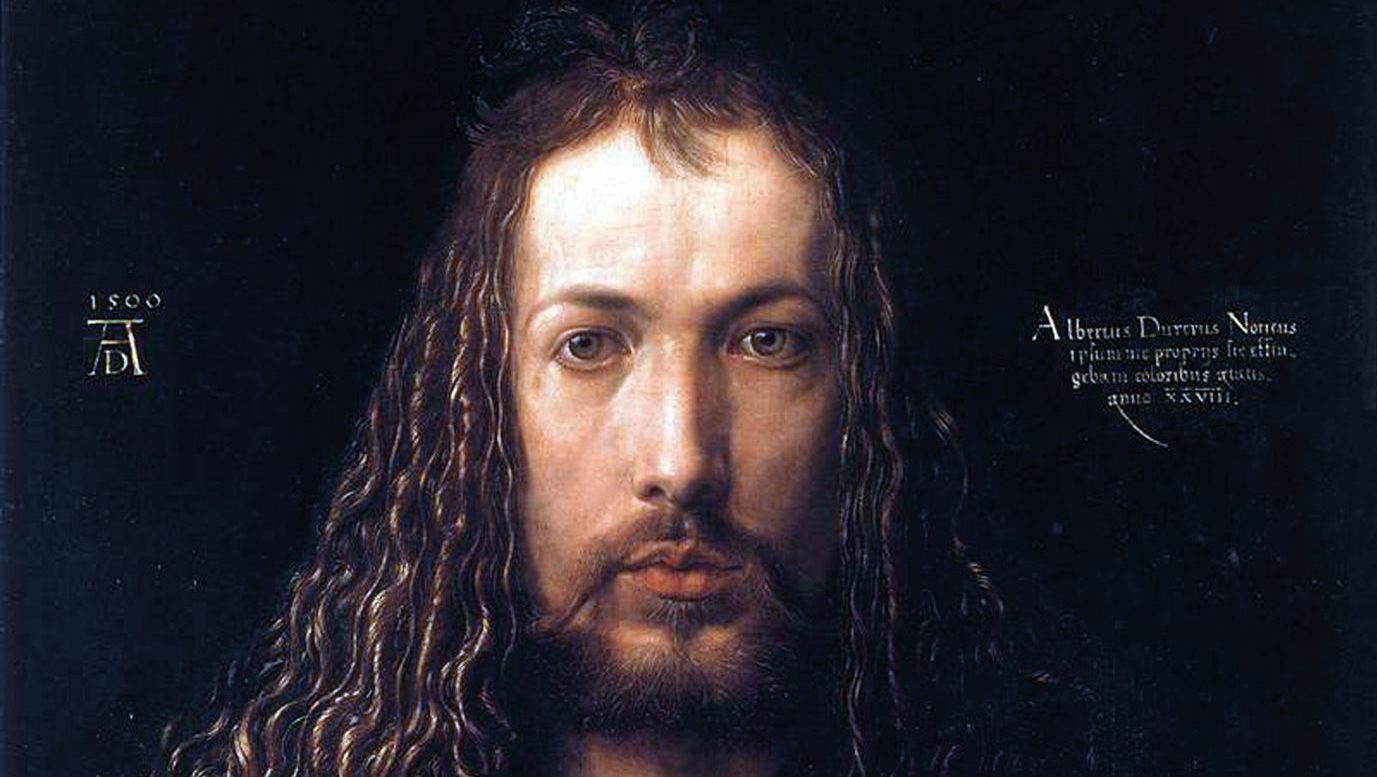

You could track the life and work of German artist Albrecht Dürer by following the lions; initially, they were based on heraldic and sculptured examples but later, with greater accuracy, on observations from life.

Or you could count out his days in coins as the artist’s purchases and sales were meticulously and regularly recorded in an in-depth and colourful journal.

Then again, Dürer’s life could be traced through his many methods and materials – woodcuts, engraving, oil painting – and myriad ways of picking out designs of staggering detail and complexity.

You might want to line him up with his contemporaries – fellow artists Leonardo da Vinci, Giovanni Bellini, Michelangelo, and Raphael in Italy; or

Quinten Massys, Cranach the Elder and Jan Gossaert in the north; or the crowned heads of Europe, and the theologian Martin Luther.

All of these stories, and more, unfold in Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist, at the National Gallery in London, the first major UK exhibition of the German Renaissance artist in almost 20 years.

The theme is well-chosen. Dürer was constantly on the move, changing

direction artistically and geographically, absorbing influences, shopping, observing, following suit. The exhibition relives those journeys and their landmark discoveries.

Born in Nuremberg in 1471, the son of a goldsmith, Dürer was apprenticed first to his father, aged around 10 or 12, then to the local painter and woodcut designer Michael Wolgemut. These days, he is best known for engravings that alchemise scratches, gouges and bare spaces on the plate or block into fur, petals, flesh and fabric on the print.

But over the course of four principal journeys, retraced in the Sainsbury Wing exhibition, he experimented with other media, notably in Venice, where he turned his hand to painting in oils.

We do not normally associate Dürer with the sumptuous altarpieces of the

Italian masters, but a fruitful connection with the ageing Bellini was hugely influential, and he exchanged small works with Raphael until the young Italian artist’s death in 1520.

Dürer’s Feast of the Rose Garlands, an altarpiece painted for the German merchants’ church of San Bartolomeo, is now in the National Gallery, Prague, in a damaged state. But a 17th-century copy in the exhibition illustrates Dürer’s apparently effortless assimilation.

Conscious that some dismissed him as “only” an engraver, this showstopper with myriad figures, a lute-playing angel and sumptuous drapery and colours, would, he recorded, “shut their mouths”.

But effort there was, and it was the artist himself who decided against all the time and travail involved in creating one-off works. Printing multiple copies from a single plate or block was more efficient and, ultimately, more lucrative.

Printing was a small family business; his wife Agnes and their maid ran outlets at the burgeoning art fairs in Frankfurt and in his home town.

Dürer was on the road, and for colour we turn not to canvas but to his journal of which only a solitary page of the original survives. Luckily, like the

altarpiece, this substantial volume was copied, and from this precious document, which is included in the exhibition, we get revealing insights into the character of the man.

So extensive is this log that it is regarded as one of the earliest journals – a traveller’s log that grew out of an accounts book, but which goes into such detail that it provides a valuable historical snapshot of the age.

From Nuremberg, the artist set out at least four times, say the exhibition’s curators Susan Foister and Peter van den Brink.

Dürer’s first journeys, from 1490 to 1494, followed completion of his art apprenticeship.

He travelled to Colmar, Basel and Strasbourg. In the summer of 1494, he went over the Alps to Innsbruck and Trent, and probably reached Venice. He certainly returned there after a gap of 10 years, painting the altarpiece for German merchants.

But it was the journey north to the Low Countries between 1520 and 1521 that was arguably to have the greatest influence on his work. This is also where he made his greatest mark, not least with the journal.

By now established and sought-after, he was given a grand reception in town

after town, and was received enthusiastically by Margaret of Austria, the daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, and the Governor of The

Netherlands. Admitted to her fine private collection at Mechelen near Antwerp, he would have seen, among other important works, Jan van Eyck’s

Arnolfini Portrait, now in the National Gallery, London.

But their informal relationship was not an entirely happy one. “In all I have done, in my living expenses, sales and other dealings in The Netherlands, in all my relationships, whether with higher or lower classes of people, I have lost out,” he complains, “and quite especially with Lady Margareta who, in

return for what I presented to her and made for her, has given me nothing.”

Lady Margareta wasn’t entirely happy either. She rejected a portrait of her

father by Dürer. “I… wanted to present it to her, but she disliked it so much that I took it away with me again.”

Candid reminiscences abound in the journal of 1520-21 with the artist’s

admiration of glamour and bling appearing unguarded. In Brussels, he

caught sight of Aztec treasures “from the new Land of Gold: a sun made all of gold… A moon of pure silver. These things are all so precious that they are

valued at a hundred thousand gulden”.

While his Italian contemporaries stayed close to home, observing the different ways and raiment of incomers, Dürer was on the road, drawing local costumes and noting local customs.

He was particularly interested in the cut of garments, such as the robes and

ornate pillbox headwear of Livonian women.

And it was his visits to zoos in Brussels and Ghent that prompted perhaps the most enchanting sketches in the exhibition: in pen and ink, a lynx, a chamois, a hamadryas baboon, washed over with pink and blue, as well as real live lions.

Only during these visits does the artist learn that the creature’s limbs are relatively short and stocky. His 1494 attempt at a lion looks comically lanky

and human-featured in comparison – which doesn’t stop it being one of the best-loved images in the show.

Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist is at the National Gallery, London, until February 27.