The telephone rang just at the right moment.

Alberto Ascari was done with kicking around the house, doctor’s orders or not. His back was still sore and his sleep was disturbed by the broken nose, but surely there was nothing to be gained from this endless boredom?

Fellow racing driver Eugenio Castellotti was at the other end of the line, checking in on how he was. That was quite the accident, he said. Ascari chuckled and agreed – yes, he never expected to finish a grand prix swimming.

Casetellotti was calling from Monza on that sunny May morning in 1955, where he and their old friend and mentor, Luigi Villoresi, were test-driving a Ferrari 750 Sport. In the background Ascari could hear engines and his stomach tingled.

I’ll come over, he told Castellotti, I need to get out of the house. Great, replied the other driver, see you soon, let’s have lunch.

It was about an hour’s drive from Ascari’s Milan home to the race track at Monza, his first time behind a wheel since the accident at Monte Carlo four days earlier. He replayed it in his mind as he drove through the Milanese suburbs into the countryside.

It must have been a patch of oil, he concluded. His great rival, Juan Manuel Fangio, had retired with transmission problems and Stirling Moss had just pulled into the pits with smoke pouring from beneath the bonnet. One of them must have leaked oil on to the track.

Moss’s retirement from the race had put Ascari in the lead, but he didn’t learn that until later. All he knew was that as he came out of the tunnel, his car suddenly veered to the right, then he was hurtling off the track. A flurry of flying straw bales, a brief awareness of being airborne, then the sea hit his face and a mass of bubbles raged around him.

Ascari unclipped his seatbelt and slipped out of the cockpit. There was a moment of silent weightlessness, a strange calm even, before he broke the surface gasping for air, tasting salt water and blood. He swam towards the nearest yacht, where a hand reached down and heaved him aboard.

He was lucky, they said, just bruises, a strain in his back and a broken nose. Rest for the week, the doctor told him as he left the hospital, you’ll be fine for the next race.

Lucky. That word again. You try to make your own luck, he told himself, you can arm yourself against fortune – but that sliver of chance you can’t control can do for you.

He knew all about that.

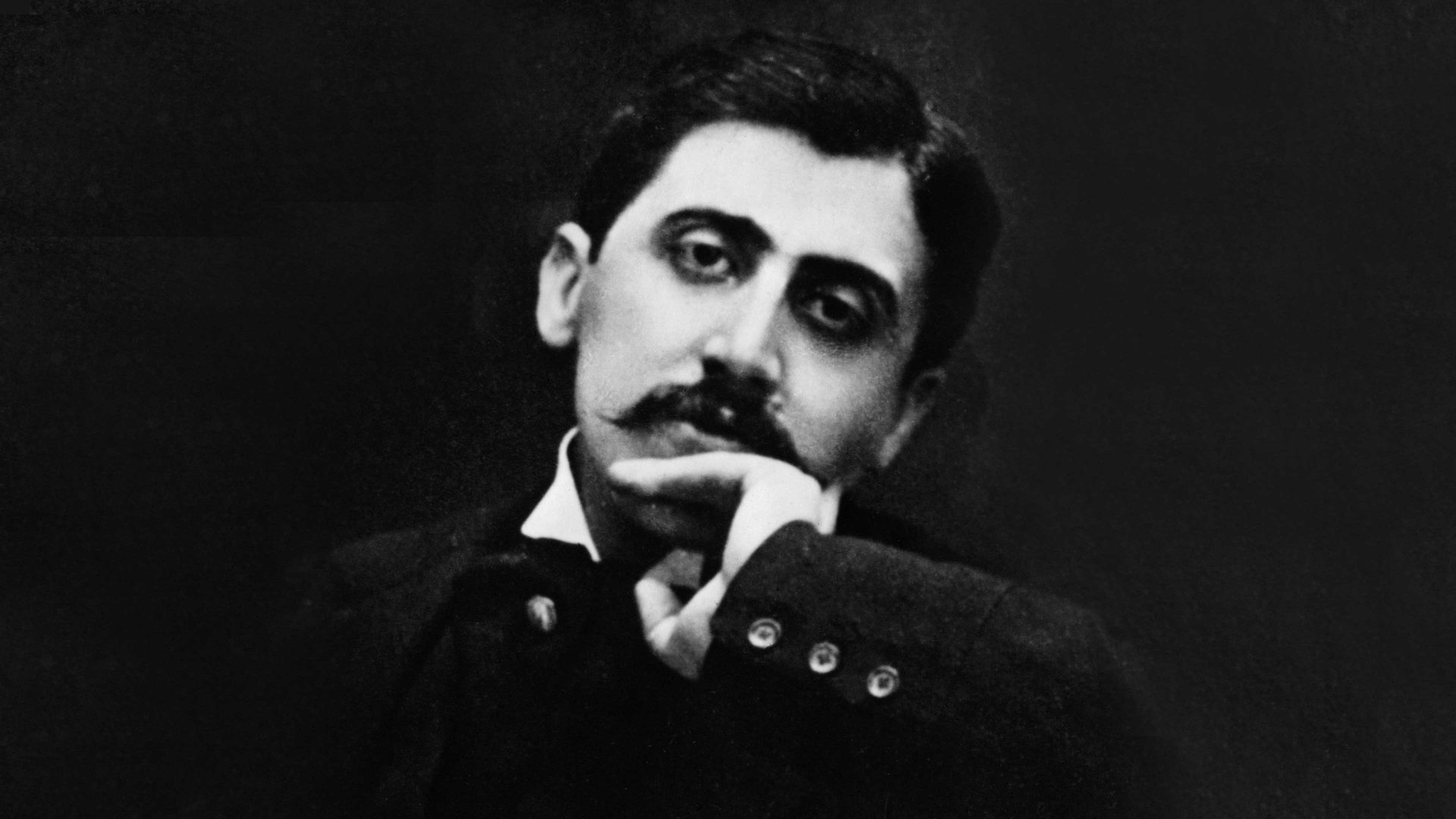

Exactly two months hence it would be 30 years since his father, Antonio, died in a French ambulance after crashing into a fence while leading the 1925 French Grand Prix. Ascari had just turned seven. He was now 36 – the age his father was when he was killed.

Numbers again. Ascari tried to control numbers the best he could. He would never race on the 26th of any month, for example; his father had died on the 26th. Ascari’s racing number was 26, the same as his father’s. Not only were they the same age, they were now equal on the number of grand prix wins: 13 each.

It wasn’t just numbers, there was his racing helmet, too. Powder blue, like the jersey in which he always raced. If he was wearing his blue helmet fate could be held at bay. He thought about the serene couple of seconds ascending through the water in Monte Carlo when he knew he was going to be all right. He’d armed himself against fate enough to minimise the chance factor.

He felt closest to his father when he was racing, seeing what he had seen through the goggles, facing the same split-second decisions, feeling the same thrill crossing the line with the chequered flag thrashing at the side of the track.

Those were the moments when he really knew his father, a man remembered faintly as a presence, a silhouette only made whole by the shared thrill of racing.

“I never want my children to become too fond of me because one day I might not come back,” he found himself telling a friend after the Monaco crash. “That way they will suffer less if I don’t come back.”

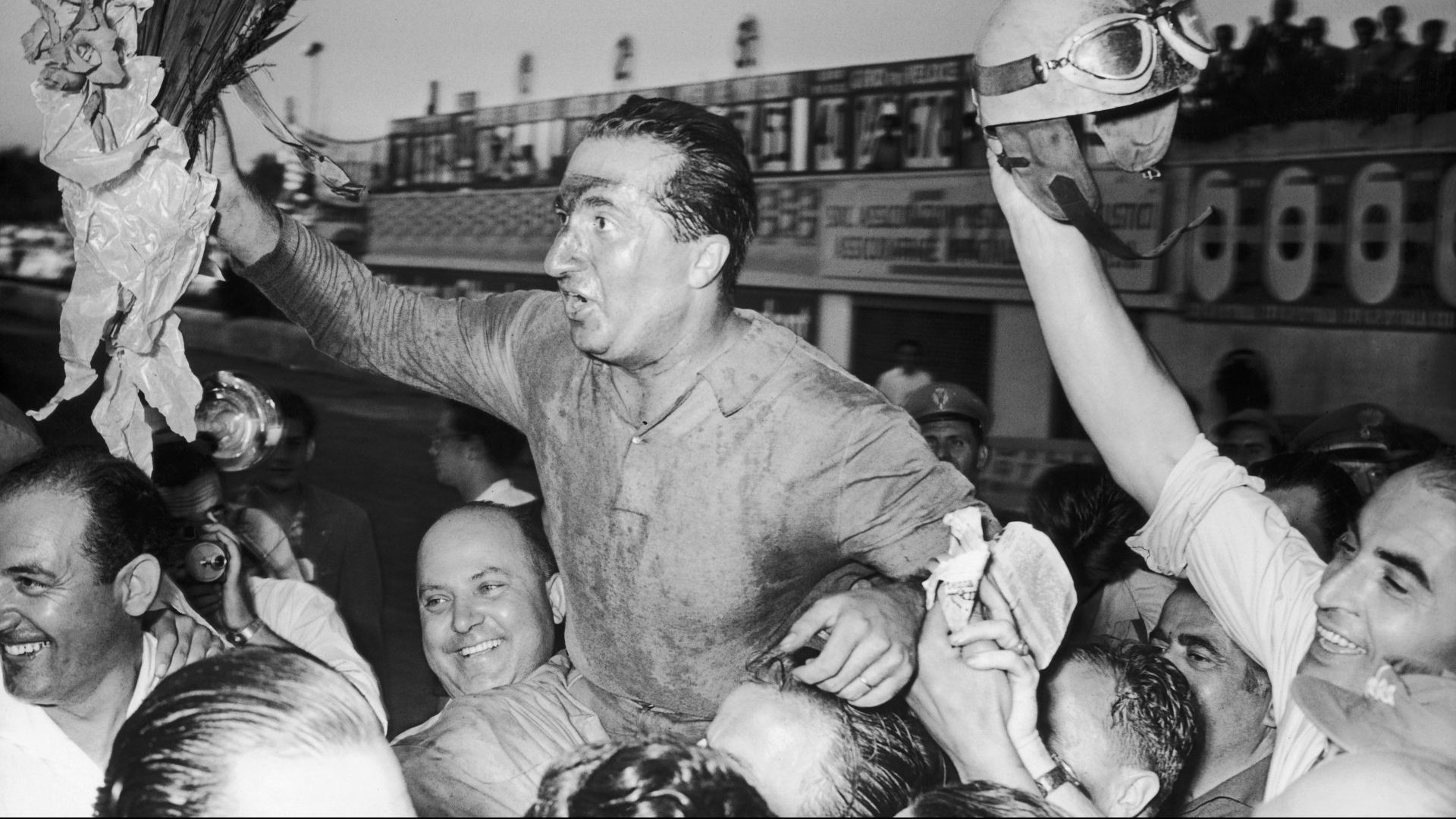

He felt good about the 1955 season, despite the weekend’s accident. He was back to his best. Ascari had won consecutive championships in 1952 and 1953 to become the first driver ever to claim back-to-back titles, but 1954 had been a disaster, his move from Ferrari to Lancia leaving him without the car he was promised until the season was almost over. He relished this season’s tussle with Fangio, who had even told him the previous year’s title felt devalued by his rival’s absence.

When Ascari arrived at Monza, Castellotti had finished his practice. He enthused about the car, looking forward to racing it in that weekend’s Grand Premio Supercortemaggiore.

Ascari, Castellotti and Villaresi walked out to the pits together and Ascari admired the sleek lines of the red vehicle. He looked from the car to the men, his mentor and his protégé, and back to the beautiful car. The graceful ascent through the harbour waters of Monte Carlo four days earlier flashed briefly through his mind.

“Let me see if I can at least fit in the cockpit,” he said. “After trying to be a deep-sea diver I want to feel what it’s like to be on wheels again.”

Once he had eased his ample form into the car and held the steering wheel, there was no way he was getting out again without driving. His lucky helmet was at home, he was in everyday clothes and, of course, the date was the 26th. This was not a race though, he thought, just me, the car and an empty track.

“I’ll take it out for a couple of laps,” he told his friends, strapping on Castellotti’s white helmet. “I’ll drive slowly.”

The second time he passed them he waved cheerfully from the cockpit. Just one more lap, he thought, pressing gently on the throttle, feeling the power of the engine beneath him on a track he knew well, and accelerating towards the left-hand bend at Vialone.

“He had no intention of taking part in the test,” said Villanesi afterwards, the first to reach the wreckage. “His love of being behind the wheel was too strong to resist. It was fate.”