I was first to arrive for Question Time, as my sister lives not far from Lincoln, where the programme was being recorded, and I took the chance to go up early and spend some time with her. So by coincidence I was on the same train as Fiona Bruce and her Question Time team.

Liz, a “never misses an episode” watcher of the BBC programme, was the first person I saw as Fiona and I walked out of Lincoln station together. “Come and meet my sister,” I said to Fiona. “She’s a fan.”

The three of us chatted away for a few minutes, at the end of which Liz asked Fiona: “Are you part of the programme team then?”

“I present it,” came the reply. Cue aghast look on Liz’s face as the reality dawned, surely one known to most women, that sometimes people look different to a TV persona when without makeup and professionally coiffured hair.

Fiona, who is as charming as they come, took it in good spirits. Liz and I also agreed that some women look just as beautiful without makeup as with it, and at the risk of sounding a bit Gregg Wallace, Fiona is definitely among them.

Maybe it is something to do with the name Fiona (he added hurriedly, lest his long-suffering partner of 45 years misunderstood).

Second to arrive in the Lincoln Drill Hall green room was Nigel Farage, wearing a splendidly cut tailor-made suit that suggested he is doing very well, thank you, in his new life as a humble backbench MP (though he wasn’t slow to suggest my podcast earnings were greater than those from his many extra-parliamentary sidelines). As he sat down, it was impossible to miss the Union jack socks, and shoes that I had not seen as well polished since my brother Donald, alas now RIP, was a piper in the Scots Guards.

Farage and I have had a fair few bust-ups on TV and in debate, and the Question Time producers were hoping for another one. Our very different takes on Brexit, immigration and net zero made sure of that.

Given we were in a strong Leave region, I was pleasantly surprised by how well my attacks on him over Brexit went down, though the best intervention came from “the man in the red jumper”, drawing parallels between anti-Jewish demonisation in 1930s Germany and anti-migrant demonisation now.

There is no point denying, though, that Farage has a certain charm, is a good gossip and raconteur, and has a take on politics and political trends worth hearing. So there were worse ways of spending a couple of hours as we waited for the recording to begin.

A few random snapshots then of the Farage worldview. He thinks Question Time hospitality – sandwiches and pork pies, bang average wine – has gone down since the days of David Dimbleby – proper nosh and a decent red; he misses going to pubs, but says he gets hassled too much; he seemed a bit disappointed that a planned demo against him was washed out by the lashing rain.

On politics, his main take on Keir Starmer’s big reset speech was that he needs to learn how to use an autocue, or read a speech without constantly looking down at notes; he thought Labour’s election campaign was ruthlessly and brilliantly executed, but that second time around the same approach won’t work.

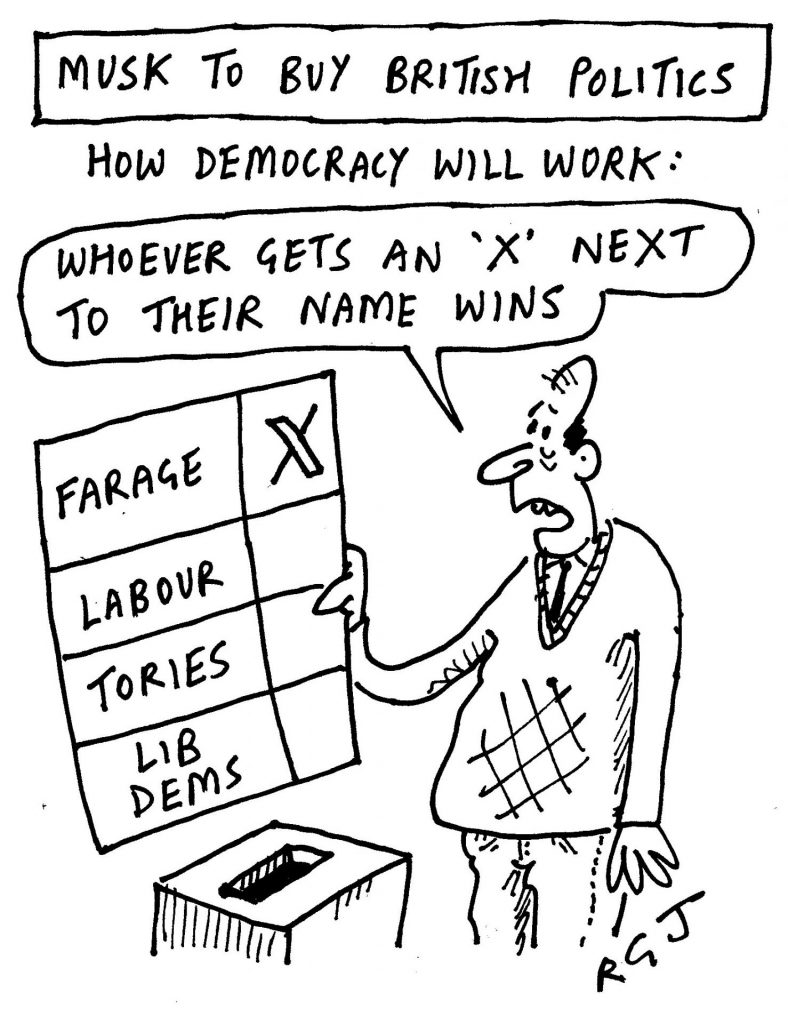

He thinks Kemi Badenoch hasn’t got what it takes, and has been shocked by the bad choices she makes for Prime Minister’s Questions; he thinks the more she tries to compete with Reform on his terms the more likely a reverse takeover of her party is possible; he has been surprised how nice most MPs have been to him; he clearly hopes the PM asks him for help in building a decent relationship with Donald Trump; he thinks Elon Musk’s obsession with Starmer is because he is a free speech absolutist who believes Labour’s post-riots reaction was to blame social media and lock up people for nothing.

Hearing his account of how Trump and Steve Bannon fell out, I sense he shares my scepticism that two beasts as big as Trump and Musk are set for a long and happy marriage – “there can only be one king”.

All of the above underlines that he views politics mainly through the lens of personality, process and media – he skim-reads 10 national newspapers every day – and rarely bothers with policy. The reason there is a spring in his step, though, is the ample evidence from elections around the world that this kind of approach often works in a cynical era when incumbency is a handicap rather than an asset.

I would not want Labour to ape Farage’s populist polarising ways. Equally, for all that the resurrection of Trump, the rise of Reform and other far right parties in Europe might anger and annoy us, we cannot be dismissive of some of the tactics they use, and need to find better ways of neutering and beating them.

When Rory Stewart and I added a weekly interview to our podcast output, Angela Merkel was my No 1 target, so it was a real treat to welcome her to our Spotify studio. In an age when so much is made of the need for charisma in politics, there is something mesmerising about the seeming ordinariness of a woman who governed one of the most important countries in the world for 16 years.

She arrived wearing the expected pinky-brown jacket and dark trousers, hair set the same way it has been for decades, keen to know the lights weren’t too bright for her subtle makeup, then keen to get on with it. “We have an hour, yes? OK, let’s go.”

As with many of our interviews, I found the account of childhood especially interesting; born in the old West Germany, her left wing pastor father deciding he was more good to the world in the East.

So she grew up under authoritarianism, with the fall of the Berlin Wall a seminal moment in her life, as in the life of the world; yet her strongest memories of that day, amid all the excitement, seemed to be her regular trip to the sauna with a friend and her determination to get home in good time because she had a busy day on the work front ahead. Work ethic and public service really do seem to be what she is about.

We chatted over the big decisions and multiple crises she faced, and of course she got to know well a huge range of fellow world leaders, from George Bush to Trump, Tony Blair to Boris Johnson, Vladimir Putin to, er, Putin. It is never easy giving up power, but my sense is that she is finding it easier than most.

Very high up my interview target list now is Beate Baumann. Never heard of her? You have that in common with most people, yet she has to be one of the most important political advisers of all time.

Never mind me or Jonathan Powell with Tony Blair, or Marcia Falkender and Joe Haines with Harold Wilson; Baumann started with Merkel in 1992, and has been her main adviser ever since. She co-wrote Merkel’s autobiography, Freedom, and it is clear that their relationship was fundamental both to the former chancellor’s rise, and her four-term longevity. Merkel states so clearly herself. Yet remarkably, they continue to call each other “Sie” rather than the more informal “du”. Beate, würden Sie bitte ein Interview mit mir und Rory Stewart tun… danke.