As teenagers, living in England, my two brothers and I all had the same nickname at school… “Jock.” We were born in England, and grew up in England, but with very Scottish parents.

The family name – clan top trumps methinks – is about as Scottish as they come. Ditto our first names. All our summer holidays were in Scotland. We always supported Scotland over England in sporting events.

Both I and my older brother (Donald Lachlan Cameron Campbell no less) learned to play the bagpipes, and when he left school it was to join the Scots Guards. So it’s not hard to see why the “Jock” label stuck.

Yet if we were made to feel Scottish in England, when we visited Scotland, our many Scottish born and bred cousins were more likely to see us as English. Many of them, my Dad being from the Hebridean island of Tiree, were native Gaelic speakers. We had accents which clearly came from south of the border.

This sense of being an outsider – Scottish in England, English in Scotland – fascinated my now, alas, dearly departed psychiatrist David Sturgeon. He felt it explained, for example, my anti-establishment refusal to consider going in the House of Lords or accept an honour, my tendency to side with the underdog, and, less attractively, the presence of a chip on each shoulder.

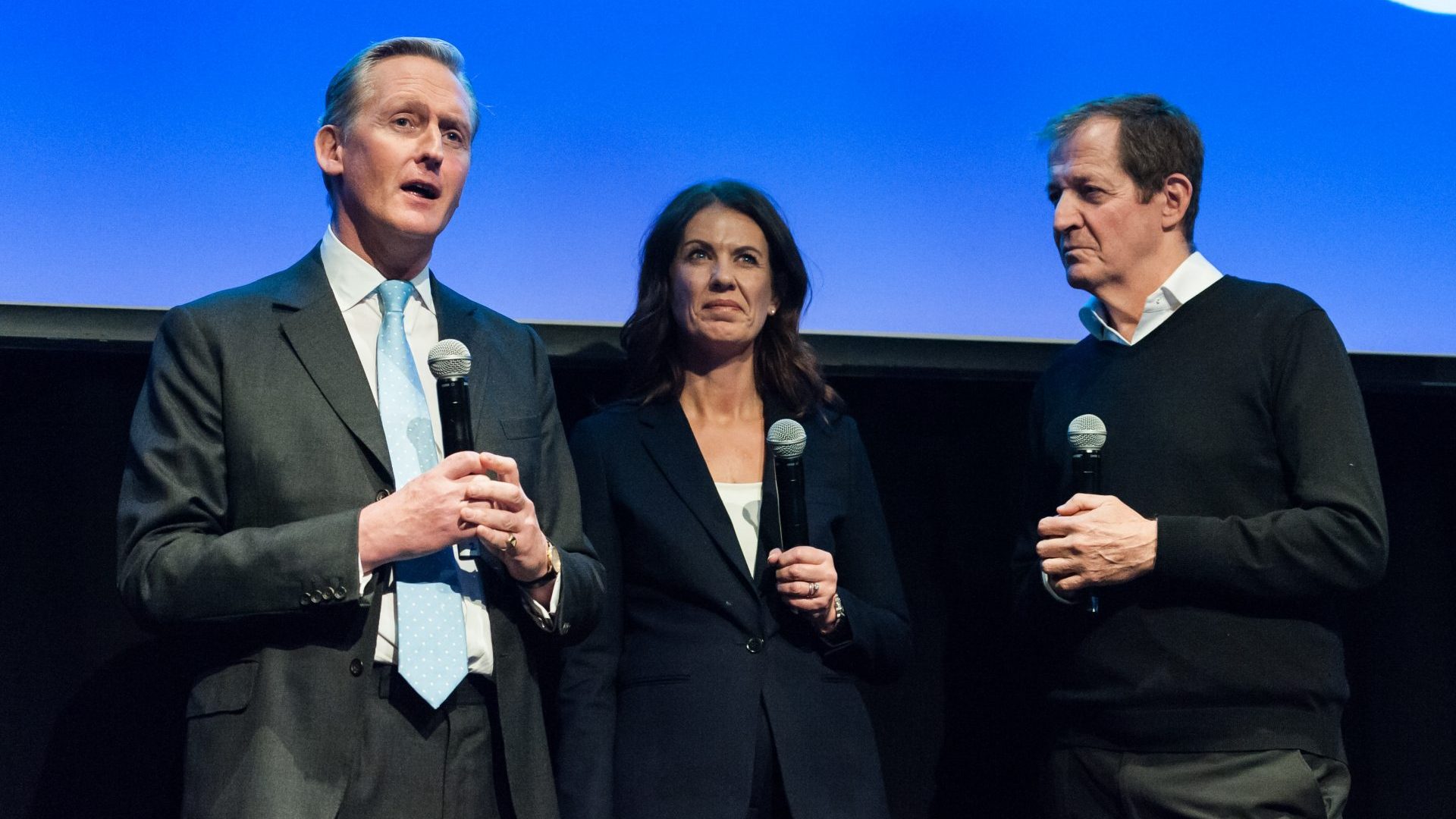

So last week I was in Scotland, first Edinburgh, then Glasgow, doing six events on the books I have written recently which aim to get children interested in politics before life, parents, friends, media and indeed politics itself make them go cynical. In each of these two great cities, the same format – first primary schools, then older kids, then adults.

Kids ask terrific questions, and one such came from a primary schoolgirl. “For the rest of your life, if you could only go to one country, Scotland or England, which would it be?” Blimey. Tough one.

Of course, there is a lot about England that I would miss, and thankfully it is an entirely hypothetical choice. But the idea of never again being able to go to Scotland, which surely boasts the greatest concentration of wonderful landscapes anywhere in the world, and in the main has nicer, warmer, friendlier people, (though I accept there are plenty of those in England too), is too grim to countenance. So Scotland it is.

Three hundred 15-to-17-year-olds packed into the Strathclyde Suite at the Royal Concert Hall in Glasgow, and proceeded to prove more Anglo-Scottish points that I have made for most of my life… that Scots tend to take more of an interest in politics, and are by and large more articulate. Again, I realise this is an entirely subjective judgment, and that just as I can find lots of politically engaged, eloquent people in England, so there are some Scots who take zero interest in politics and can’t string a sentence together either. But it is my column, and I’ll generalise if I want to.

I asked for volunteers to come up and make a one-minute speech about something they really cared about. First up, Daisy, who admitted to being “really nervous”, but got into her stride after a few deep breaths and passionately made the case that we should treat refugees far better than we do. Indeed we heard from a refugee, a girl from Gambia called Fatima, who now lives in Govan, and spoke of the need for government to focus more on communities that felt left behind (she meant Govan, not Gambia).

There was Kai, who argued for higher taxes on the richest 5% (and later contacted me to ask how he could get into politics). We had a speech arguing for compulsory voting, one on the need for a housing revolution, while a girl called Sarah, though not a Gaelic speaker, used her minute to argue that Gaelic should be taught in schools as a way of protecting and preserving Scottish culture.

Dom, from St Andrew’s Secondary, explained why working-class people were smarter than upper-class people, and on a similar theme, Brogan argued against private education, saying the state schoolchildren in the room had to fight way harder for success, and if levelling up meant anything, it should be about equality of opportunity.

Individually, they were all really good. But taken as a whole, nine teenagers coming up, with no time to prepare, no notes, and a hall full of their peers and teachers staring at them, they were brilliant. Next to no umming and aahing. Lots of passion and humour. Good ideas.

As so often when I spend time with young people, I left feeling more hopeful that we can get ourselves out of the social, economic, political and democratic mess we are in.

Eton, which has produced three times more prime ministers than the Labour Party, has a multimillion-pound debating chamber in which pupils can hone their public speaking skills. These kids were good. But how much better would they be if they too had, as part of their school life, training in public speaking and debating that the Johnsons and Camerons of this world took for granted?

Dom, who had the broadest of broad Glaswegian accents, was the only one to drop an F-bomb in his speech, to illustrate his belief that the toffs are not as smart as they think they are. As he finished, to loud applause, I asked his teacher if he would be reprimanded.

“Given how much we know that you swear, Alastair, probably not,” he said.

Good kids, good teachers.

You may have noticed that independence did not feature in any of the speeches. That doesn’t mean nobody in the room was in favour of Scottish independence. But it does mean that the issue’s salience has fallen – one of the reasons, alongside their poor performance in the general election, for the somewhat gloomy mood surrounding the SNP conference in Edinburgh over the weekend.

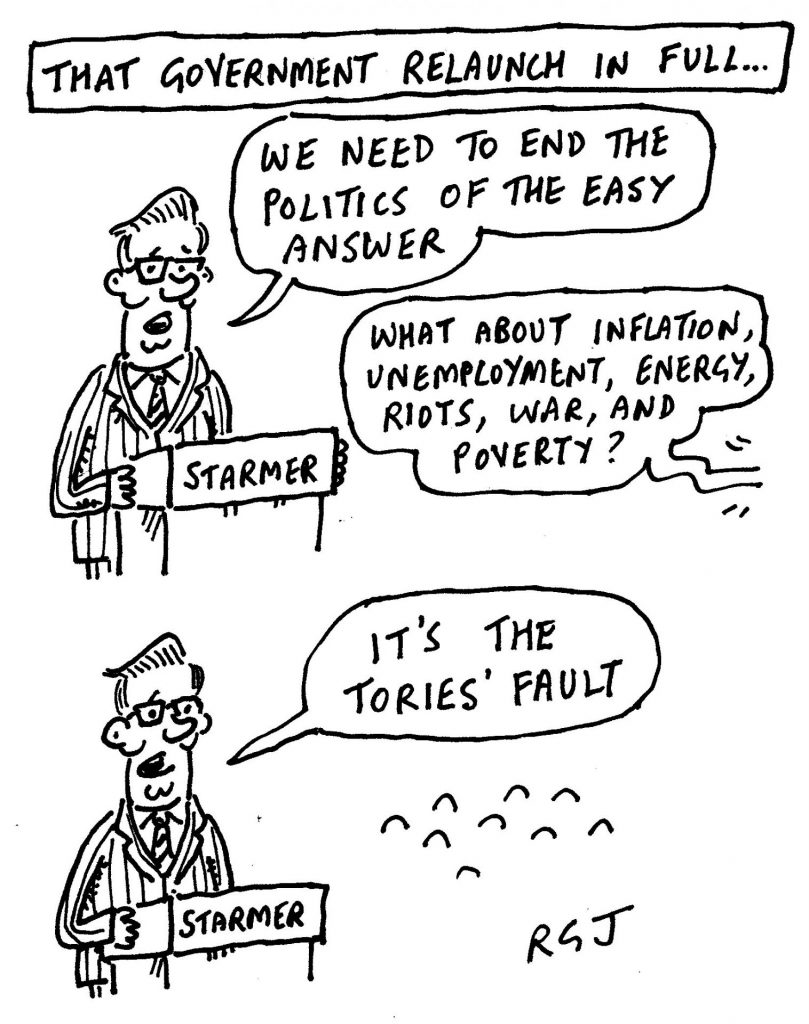

Both Brexit and Boris Johnson are widely loathed in Scotland, and that post-Brexit period, mid-Johnson premiership was surely a high watermark for the best possible conditions for a drive towards independence. That the dial has moved backwards since then, allied to scandals, squabbles and lack of progress on the public services for which SNP-led governments have been responsible, explains the broad smile on the face of Scottish Labour’s leader Anas Sarwar when I met him for dinner.

He is a very warm and smiley person anyway. But the success of Labour in the UK general election, and the continuing struggles of the SNP, combine to give him a fair bit of confidence that the chances of him being first minister after the next elections to the Holyrood Parliament are shifting in his favour.

Shout out for the ticket inspector on my train home, also called Alastair, who was so nice to a blind guy called Jim who was on the train with his guide dog. At every station stop, as we pulled out, Alastair made an announcement, saying there was a guide dog near the cafe in Coach C, asking passengers to be careful not to tread on his paws, and urging children not to play with him “as he is working.”

He also made a visit to the cafe to get Jim food and drink, as well as water for the dog, and chatted to him for those parts of the journey when he wasn’t checking tickets.

Alastair, it was clear from his accent, is Scottish. What was it I was saying? Nicer, warmer, friendlier… give that man a pay rise!