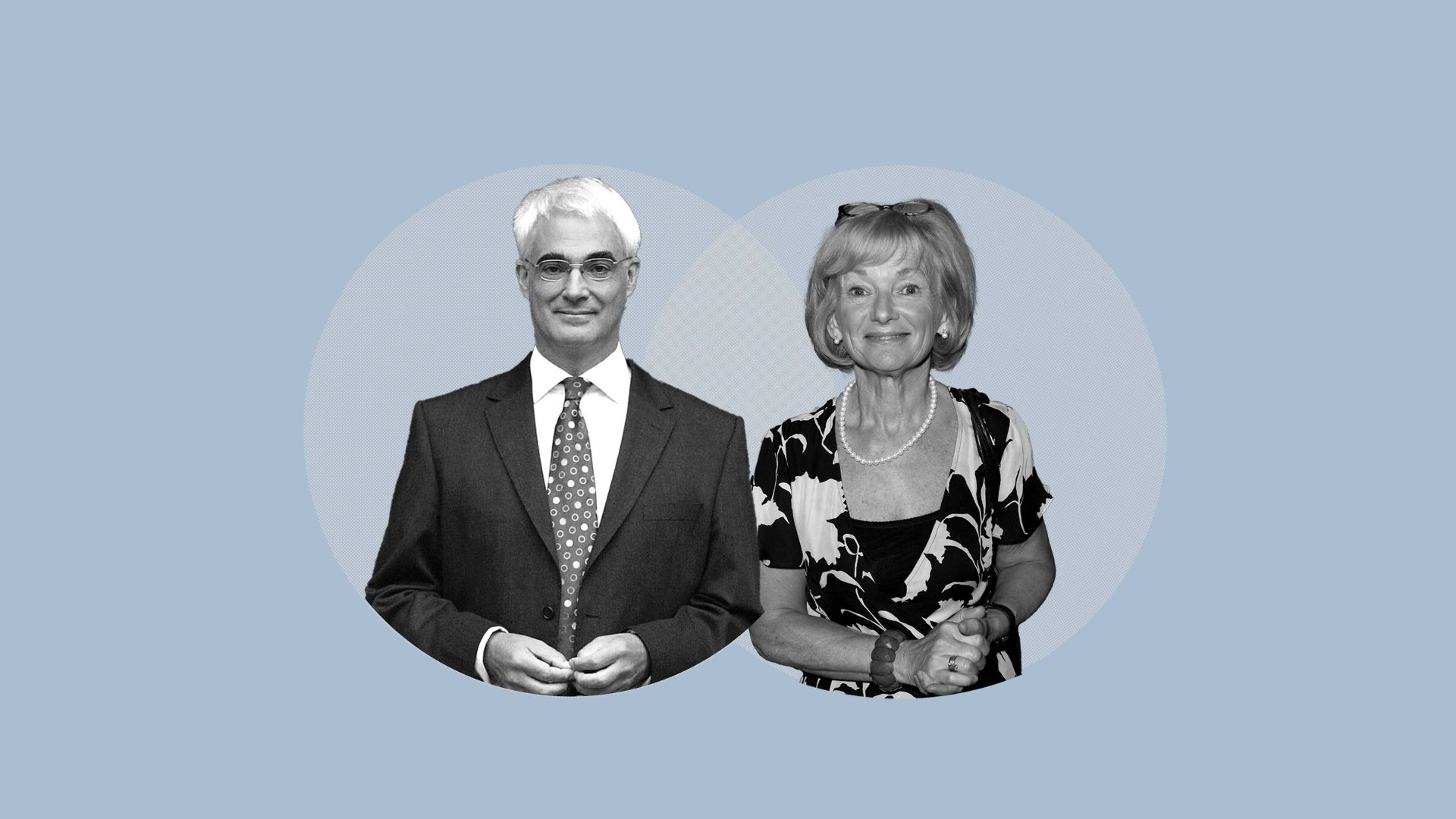

Well, that was not the best of weeks for the Labour family… first Alistair Darling, then Glenys Kinnock, taken from us.

Neil could not have had a more loyal and steadfast life partner as he led the Labour Party on the first, important steps of modernisation that eventually took us back into power under Tony Blair. Fiona and I could not have had a more loving and loyal friend. Though we knew her death was coming, it was still a dreadful blow when it came.

Their son Steve, to his mother’s immense pride now a Labour MP in a Welsh seat, made a very interesting observation: that though the death was painful to the whole family, one consequence was that memories had come flooding back of the time before she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s six years ago.

It has been sad, especially for Neil and the close family, to witness the change, though at least he can take some comfort that she died peacefully, at home, loved by him to the very end. Theirs was a partnership perhaps as strong as I have ever witnessed in a couple, and it is not easy to imagine one without the other.

Most of you will have seen elsewhere the details of her life and her own political career, which followed Neil stepping down as Labour leader after the 1992 election: as an MEP, then as a minister under Gordon Brown, able to represent the UK in three areas in which she had both passion and expertise: Europe, Africa, and the United Nations.

So perhaps you won’t mind if I use this space for some more personal memories. Like when she and I visited Eritrea together in the 1980s, she for a charity, me for the Mirror, at the height of a war, going for several days without a bath or a shower, and I couldn’t understand how she managed to look so smart and elegant. Indeed, I cannot think of a time when she didn’t look smart and elegant. Our friend Lindsay Nicholson, who edited Good Housekeeping, used to say that Glenys was Good Housekeeping in human form.

I can recall the stoicism she displayed whenever not just Neil, but she, came under vicious attack from sections of our media. She knew they were doing it to get at him, and was determined “not to let the bastards get us down”. So out came the smile, and the friendly chat, and on went the campaign.

Defeat in 1992 was hard to take. Indeed the mood on the journey back from South Wales was not dissimilar to that which accompanies a death. The next day, with John Major back in Downing Street, and just a gaggle of photographers left outside the Kinnock home in west London, Fiona and I went to see them, and it was Glenys who was keeping spirits up. Great food – always, great food when she was doing the cooking – and great chat. It was impossible, even in those circumstances, to leave her company without feeling better than when you arrived.

Then there were the holidays, with Glenys wheeling out the karaoke machine, and nobody allowed to sit it out. Some of those holidays coincided with crisis times in government, not least in 2003 when I had to head back from France to London to give evidence to the Hutton inquiry. I am not sure if I would or could have prepared for it as I did without the emotional support she and Neil gave me at the time. There were times in government when I suspect there were things we did that did not totally win her approval. But if Glenys was your friend, she was always on your side.

Perhaps her feminism is the thing that did not come over as strongly as it might have done in the tributes on the day of her death. Our daughter, Grace, will for ever keep the hilarious book of photos, drawings and captions that Glenys made for her when she was born, warning her that she was entering a man’s world, and would have to keep her wits about her to make her way. I think Glenys can take some of the credit for Grace now being a feminist comedian!

She and Fiona co-wrote a book for Virago Press in 1993, By Faith and Daring, sub-titled “Interviews with remarkable women”. There were indeed some remarkable women in there. But few if any were as remarkable as Glenys. We feel blessed to have known her as a true friend and political soulmate, loved her as friend and political soulmate too, and to have been loved in return.

On the day the sad and shocking news came through that Alistair had died, Matt Hancock was getting tied up in knots at the Covid inquiry, and Esther McVey was making a fool of herself on BBC Question Time. And I was feeling not just sad at the loss of a friend with whom I had worked closely for many years, but shocked at how fast and how low our politics has fallen.

I often felt Alistair underestimated himself as a politician. His modesty and humility were genuine. I cannot recall a single occasion when he sought preferment or promotion for himself. He was the ultimate team player. If there is one lesson from his life and times, it is this: politics needs good, honest, principled, hard-working, serious people more than it has ever needed them. Alistair Darling was one of those people, and we should never forget the value and the values of his public service.

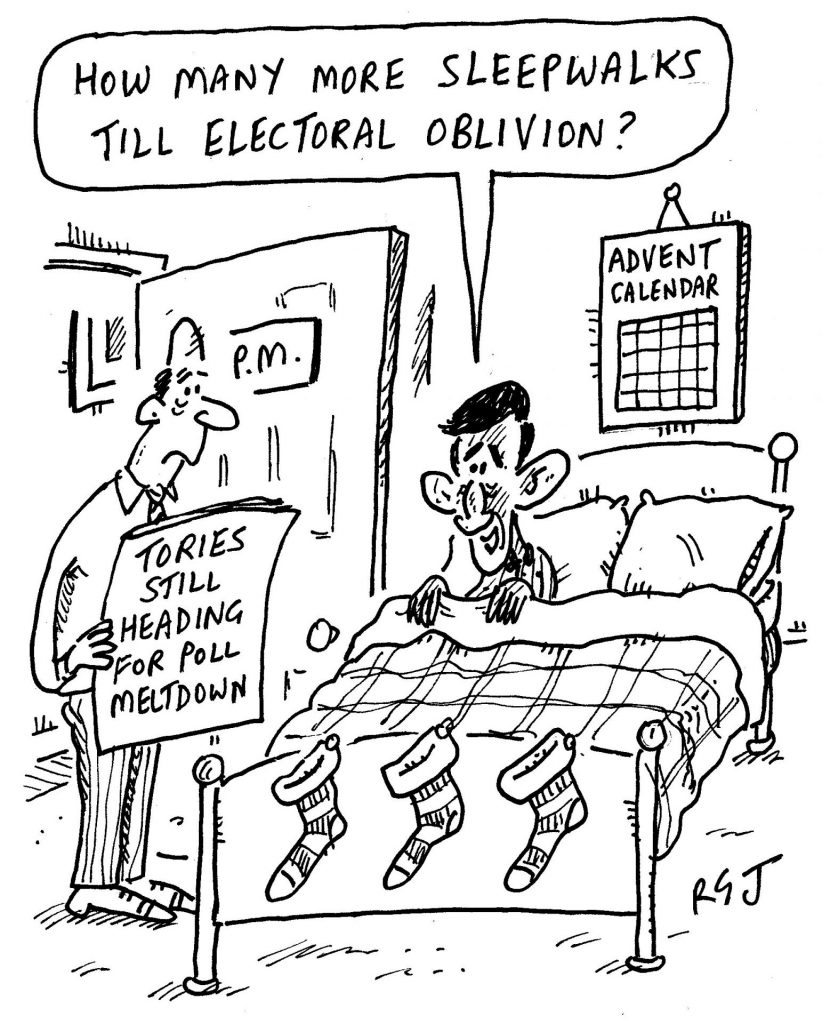

There is always a risk of hypocrisy in death, when politicians who have spent years attacking you suddenly lavish you with praise. I understand it to some extent, but I think some of the Tory tributes to Alistair might at least have acknowledged that at the time, far from praising his calm steering of the economy through the global crash, they made it the centrepiece of their entire re-election campaign in 2010 and beyond.

There was “the mess we inherited, the mess we inherited, the mess we inherited…” and then, five years later “don’t give the keys back to the people who crashed the car…” Alistair didn’t crash the car. He was at the wheel when the US sub-prime mortgage market sent the car careering towards a cliff, and Alistair was somehow able to steer it back on track, and prevent a crisis from turning into a catastrophe.

I hope, as they delivered their tributes, the Tories allowed themselves at least a moment or two to reflect that it was the kind of brutally successful but often dishonest political campaigning that Alistair found somewhat distasteful, whoever was doing it.

My partner, Fiona, used to write profiles of MPs and peers for The House magazine, and in 1991, four years after he became an MP, her subject was Alistair. Looking at the interview today, several decades later, there is one passage that really stands out, and underlines the point about him being a creature of government, someone serious about politics being an agent for change.

“I support what Neil Kinnock has done [to modernise the party] and there are some people whose views I can’t understand. If you spend too long opposing things, you forget what you are in favour of. I joined the Labour Party to see things change, not to complain about what other people are doing, and if we don’t get another Labour government we are never going to get any change at all.”

Amen to that.