Rishi Sunak was head boy at Winchester College. Jeremy Hunt was head boy at Charterhouse School. Both loudly reject Labour’s proposal that private schools should be deprived of their charitable status, through which some of the wealthiest families in the country, like theirs, have their education subsidised by some of the poorest.

Their argument, plundered with the help of bogus stats produced by the private schools’ lobby group, is that if the charitable status were removed tens of thousands of parents would send their children to state schools, putting further pressure on the state education system. My argument is that if the better-off in Britain, not to mention senior politicians, used state schools, the pressure on government to improve education for the many, not the few, would grow.

Hunt said Sunak’s passion was good education for all, which sits very badly with the prime minister’s spending on his own children’s education five times the per-pupil amount in the state sector. Levelling up? I don’t think so.

The tax break for Winchester and Charterhouse, Eton and Harrow et al costs the Exchequer £1.7bn, which Labour has said it will use instead to hire more than 6,500 new teachers and give every child access to a mental health counsellor at school and professional careers advice. For all Hunt’s talk of difficult choices, that strikes me as quite an easy one unless, that is, your policies are directed at maintaining the privileges of people like yourself, while talking the talk about your commitment to supporting the poor and the vulnerable.

Meanwhile, Eton was back in the news again, having invited Nigel Farage to speak there. I don’t have an issue with him being invited to speak, as whether we like it or not, Farage has been a significant political figure. What I do have an issue with was the treatment by Eton’s “scholars” of girls from visiting state schools invited to the event, who were subject to misogynist abuse and racial slurs, sufficient for a number of pupils to be “sanctioned”. Next stop the Bullingdon Club for them, I imagine.

The Johnson-Sunak-Hunt clan like to think the “top” private schools are part of what make Britain great. On the contrary, they are a big part of what is wrong with Britain; drivers and defenders of inequality, the entrenchment of outmoded attitudes about our past, present and future, the holding back of natural talent outside the gilded circles of wealth and privilege.

Without their schools and universities (all three went to Oxford) on their CV, would any of Johnson-Sunak-Hunt have risen as high as they have? Unlikely methinks, all things considered – such as the wretched state of our economy and public services, and their central role in creating it.

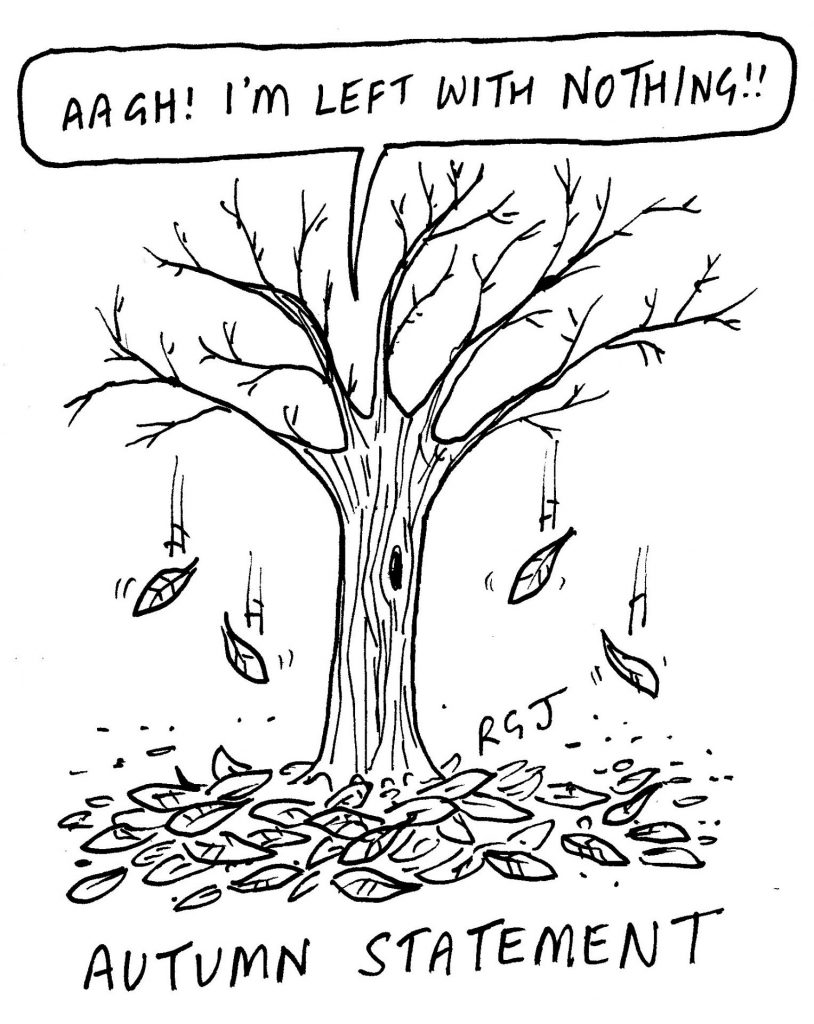

I was pretty sure that my long-planned talk at the Bank of England last Thursday would be cancelled. After all, surely the governor, Andrew Bailey, had better things to do than listen to me on the day the chancellor was unveiling his plans to raise taxes and cut spending in an attempt to undo economic damage done by several predecessors. Among them Boris Johnson’s right-hand man, Mr Sunak, now busily trying to pretend the economy was swimming along nicely prior to war in Ukraine and KamiKwasi Trussonomics.

But the meeting went ahead, in the theatre-style room you may have seen on TV from time to time, most recently when the Bank had to limit the carnage inflicted by the KwartengTruss mini-budget. Relax; I was not being called in to give my advice on fiscal and monetary policy, but was there to talk about mental health, almost a full decade since I helped to launch a new mental health network in the same room.

The Bank was one of the first major national institutions to sign up to the Time to Change campaign, which was founded to help change attitudes to mental health, and reduce stigma and discrimination around mental illness. Under both David Cameron and Theresa May, the government supported the campaign, which sadly was yet another victim of the wretched Johnson era. Funding stopped, and with it the campaign. Short-sighted but predictable, I guess. Thanks for nothing, Rishi.

Mental health has fallen down the agenda in recent years, partly because other priorities have crowded in, also because the government has failed to give the leadership required to keep up the momentum.

However, the business community has continued to do its bit, both for moral and compassionate reasons, but also because the best businesses understand that they are likely to be more productive and profitable with a happy and healthy workforce, where people can be open when they are struggling, and feel supported.

Having been at the Bank of England last week, this week I chaired a session on all this at the CBI conference, a further sign that business is taking the issue more seriously than the government.

The Bank of England has had to deal with plenty of crises in its time, not least when it stepped in to prevent market-spooking mini-budget carnage becoming cataclysmic calamity. Andrew Bailey spoke very frankly about the stress under which he and others operate in moments like that, and we both mused on the additional pressures brought to bear by living in the public and media eye.

Simply talking in that way in front of staff, as he did, was an act of leadership, and it was clear to me from the Q&A that followed our discussion that the environment was one in which people did indeed feel they could be open, and knew where to go for support in times of psychological distress. There was a palpable difference in mood and attitude from my last visit a decade ago.

Change is always likely to be quicker if the government of the day is fully signed up to it. But progress can also be made despite government, and in the mental health field, not least thanks to business and economic leaders who understand why this is so important, that is happening.

Most of the big banks had to deal with the fall-out from staff suicide during the global financial crisis, which seemed to act as a spur to better attitudes and understanding. Suicide was also on the agenda at another event I spoke at, organised by women working in the rail industry, whose employees are often on the mental health frontline – up to and including dealing with people jumping from bridges and lying down on the tracks.

Women In Rail exists to try to get more women into the industry, and of those who are in it, to get more into top jobs. The stats were pretty stark: 16% of the industry workforce are women; 1% of the industry’s senior executives are women. That is not exactly moving with the times.

To Foyles bookshop, to stock up on a few German-language books to keep my language development going. A 13-euro paperback is now almost £20. Who would ever have guessed that leaving the single market would have made things more expensive when an EU export became a UK import on the bookshop shelf?

Mentioning this to a friend who works in publishing, I hear the problems go a lot further than the price of my German books. Much of the paper required for printing books comes from Scandinavia, and it has become more expensive, and in shorter supply, because of Brexit. Freight is more expensive, and while Vladimir Putin-induced higher energy costs are a factor, so was Brexit before the invasion, and it has continued to be since.

Then, adds my friend, there is that other unquantifiable but nevertheless highly significant of factors: hours spent sorting out paperwork. The old red tape that the liars and charlatans said Brexit would put paid to.