So it is Mental Health Awareness Week – again – and for all the progress we have made on attitudes in recent years, the sad reality is that we are going backwards on services. At least David Cameron and Theresa May talked the talk, saying there should be parity between physical and mental health, and that it was unacceptable that people in distress had to wait so long before getting access to treatment.

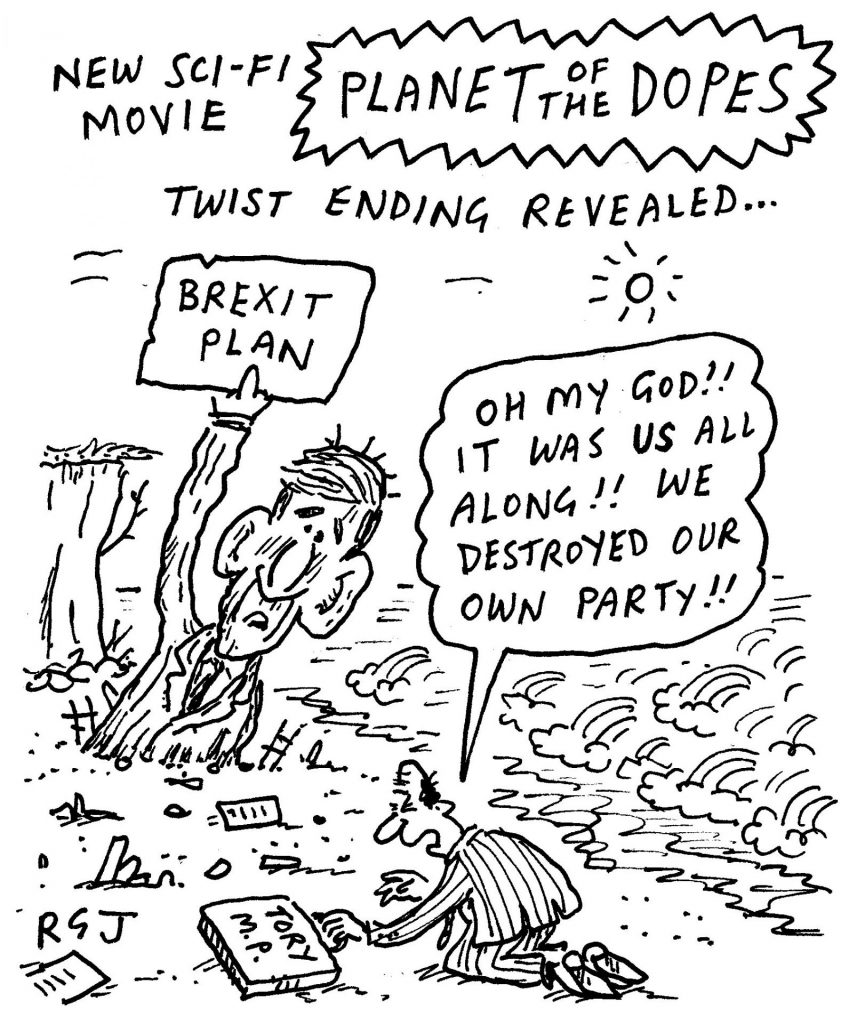

Since Brexit and Boris Johnson, however, even the talk seems to have stopped, and Rishi Sunak’s recent “sicknote culture” speech, and his downplaying of the role of actual, er, doctors in deciding who was genuinely ill, represented a backward step on attitudes, to match the backward steps on services, which mean even seriously sick children get shipped around the UK because of a national bed shortage, and a real crisis in child and adolescent mental health services.

Last week, I spoke at a charity event in the City of London, where a businessman named Tim Watkins told of the phone call he received to inform him that his son, Charlie, had taken his own life. It was heartbreaking to hear. This Thursday I will be in Sheffield, for a conference on suicide prevention, the brainchild of another father, ex-journalist Mike McCarthy, whose son Ross killed himself aged 31, having been diagnosed with severe depression. Ross was told he definitely qualified for talking therapy, and he would be able to see someone… in six months’ time. He left a note, in which he wrote: “Please fight for mental health. The support just isn’t there.”

His dad, to his enormous credit, has done nothing but fight for mental health since, and Thursday’s event is but the latest initiative. His charity, Baton of Hope, is launching the Workplace Pledge, reflecting the role that employers can and often do play in supporting those at risk of suicide.

I lost a cousin to suicide almost a quarter of a century ago, and I think of Lachie often, now that his children are all grown up, and he would have been a grandfather today, had he not decided to end it all. Suicide is the ultimate in mental illness, awful for that individual driven to it – I have been close but never gone beyond the edge – and life-changingly awful for family and friends left behind.

Suicide is now the biggest killer of men under 50 and women under 35. Imagine for a moment that we deleted the word “suicide”, and inserted “asthma”, or “diabetes” or “leukaemia” in that sentence… do you not imagine that the issue might be higher up the political agenda, rather than being pushed lower down, by a prime minister who would prefer to imagine the economic problems for which he is responsible would be all too easily solved if people would just stop pretending to be mentally ill?

Mind, the charity for which I am an ambassador, is going into Mental Health Awareness Week with the slogan No Mind Left Behind. It is a tragedy, and a national scandal, that they need to. But the truth is that all too many minds are being left behind by a government whose response to genuine need, in this as in so many other areas, is to pretend that it doesn’t exist, rather than accept the responsibility to address it.

New Zealand’s Labour Party asked me to be the guest in the first of their series of online gatherings under the banner Ideas for Tomorrow. In discussion with former PM and now leader of the opposition, Chris Hipkins, I put the case for the kind of anti-populism I highlighted here last week when writing about Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the Greek prime minister.

I also suggested opposition was the best place from which to campaign for political reform, and that New Zealand having successfully changed their voting system, Labour should now seek to change the three-year parliamentary term.

It might seem counterintuitive for an opposition party to want to give an extra year to an unpopular government they are seeking to oust. But in New Zealand and Australia, there seems to be common acceptance among politicians that the three-year term is a problem, and though constitutional change is always tricky (as the Australians found out with their Indigenous Voice referendum) surely they can find a way to fix this particular obstacle to the kind of long-term approach that voters consistently claim they would like to see.

German newspaper the Süddeutsche Zeitung wanted to interview me about Jürgen Klopp, and the influence Liverpool FC’s soon-to-leave manager has had on UK life and culture. Correspondent Michael Neudecker’s interest was piqued by an open letter that I wrote on these pages two years ago, under the headline, “Dear Mr Klopp, you’re wasted in football”, in which I asked the question: “Why can’t politicians be more like Jürgen?”

Of course, any Liverpool fan, sad that he has just one more game to go, will tell you that Klopp has been far from wasted in football. He is firmly embedded in the list of Liverpool managers whose name will for ever be remembered in songs sung and flags flown on the Kop.

My point remains that Klopp is one of that small number of sportspeople whose reach extends well beyond sport, and whose leadership and communications skills modern politicians would do well to study.

Authenticity. Empathy. Passion. Principles. Humour. Innovation. Understanding what a community is. Love for his team. A loathing of populism (he can’t understand how a country as great as ours could put the likes of Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage in positions of power and influence).

He is also very good at dealing with the media, not an easy task for top football managers, who are required as part of the job to do many more press conferences and interviews than prime ministers and presidents. Klopp will not miss the constant attention, but for sure the press will miss the quick wit, the friendly banter, the openness, the insight. He does look tired, though, and it is not hard to see why he has decided to take a break.

Given the energy that is his trademark, however, I cannot see him putting his feet up for too long. What price a Germany win in the 2030 World Cup, under the leadership of a 62-year-old Klopp? We have not seen the last of the biggest smile in football, on the face of Britain’s favourite German.

Well, that was a nice, and rather moving surprise. Fiona and I went to see American jazz singer Stacey Kent, whose music I randomly discovered a while back as it played in the background in a French restaurant, at Ronnie Scott’s, the famous Soho jazz club. Halfway through, she announced to the audience that her favourite podcast was a British one, and that it kept her and her husband and fellow musician Jim Tomlinson company as they travelled the world.

When she named it as The Rest Is Politics, the audience reaction suggested that Rory Stewart and I have cornered the jazz-fan market. And when she said she saw me as a “symbol of hope”, Fiona, who knows my grumpy side better than anyone, whispered: “Is she talking about you?”

Yes, she was! And if that wasn’t good enough, Stacey then told the audience, rightly, that my favourite singer was Jacques Brel, and my favourite song Ne Me Quitte Pas, a version of which she proceeded to sing, beautifully.

Thankfully, the lights were low, so nobody could see the tears…