As the pollster Peter Kellner pointed out in TNE last week, the numbers of people now seeing Brexit as a mistake are steadily rising, which makes the cross-party omertà on the subject all the more bizarre. His article reported a number of recent polls, all showing a clear majority who would vote to be in the EU if they had the choice now, and who now believe Brexit was the wrong choice for the country.

But just as in general polling, the question that always interests me most is whether people think the country is going in the right direction/wrong direction (majority in the latter camp right now, unsurprisingly). So with regard to Brexit, the question I would like to see tested is whether people think it is going well or going badly. I think the numbers would show a huge lead for badly.

I now test this question with any audience I speak to. At a dinner attended by 80 headteachers last week, there was unanimity that Brexit was going badly. In an audience of more than 200 investment analysts earlier in the week, one hand was raised for the notion that it was going well. When I asked the owner of the hand why he had raised it, he said: “Because I’m from Wigan.” It raised a laugh, but fewer and fewer are finding the Brexit story funny any more.

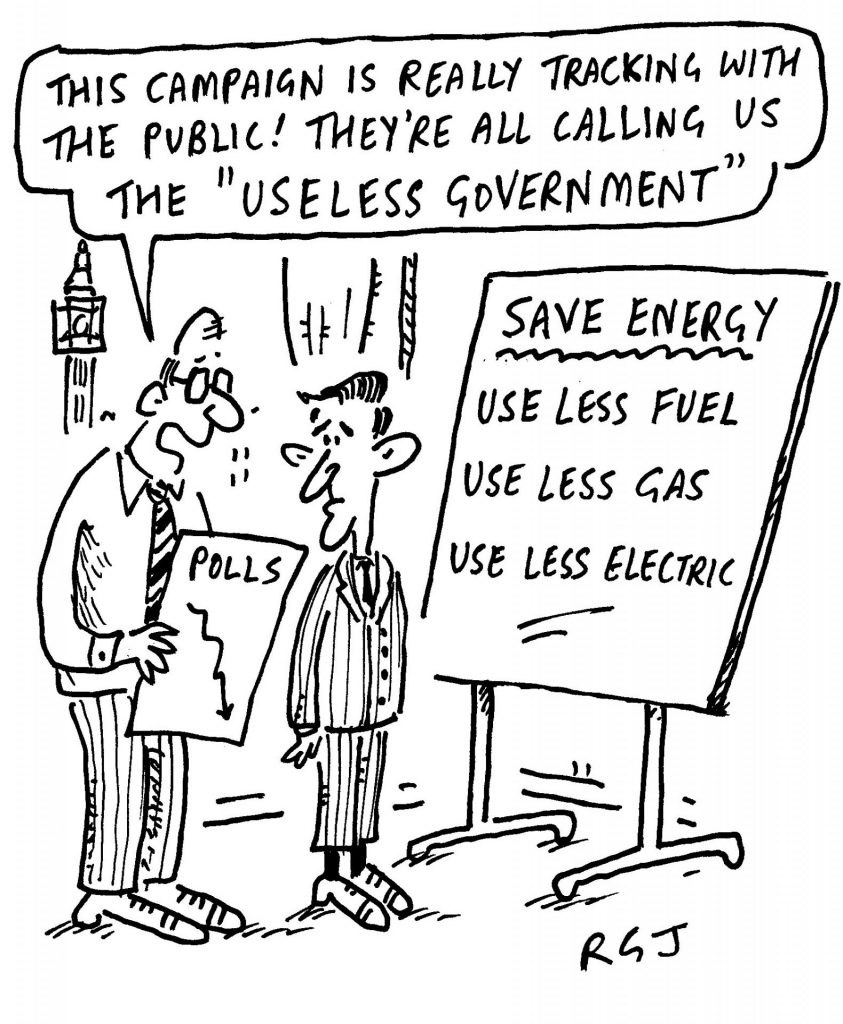

As if the political class is not feeling enough opprobrium directed towards it right now, it is surely adding to it to have such an elephantine problem sitting defiantly in the centre of the room, around which they all seem content to tiptoe as though it were not even there. Both main parties want to put growth at the heart of their economic agendas, yet refuse even to contemplate the reality that the elephant is dropping gigantic growth-sapping, economy-shrinking, investment-draining turds all over their strategies.

That reality was clear in a couple of recent interviews with ministers which, if you missed them, are worth looking up.

First, Nick Robinson on the Today programme, asking Michael Gove to explain how Brexit has benefited businesses. Bearing in mind Gove was one of the key architects of Brexit, and is reputedly one of the government’s better communicators, his failure so to do was stunning, especially given how many times Robinson asked him to.

Then there was the skewering of sighting of an increasingly irritable Jeremy Hunt by Beth Rigby on Sky News. All too often interviewers let the minister dodge and deflect for a couple of questions, and then allow themselves to be moved on. Rigby stuck with Brexit for a good six minutes, ignoring Hunt’s pleas to be able to talk about other things, rooting her questions in the hard facts of lost trade and stunted growth as explained by the Office for Budget Responsibility. She exposed Hunt as positively Trumpian in the way he had based his entire market-stabilising strategy on the authority and credibility of the OBR; accepting their findings when it suited him, but rejecting them when it didn’t, as in their judgement that Brexit was taking a 4% chunk out of the economy and hitting us to the tune of over £100bn.

There was a lot of talk about a fiscal black hole in the run-up to the recent budget. Far bigger is the Brexit black hole. The fiscal black hole was a political invention to assist the Tories in their political operation to bury KamiKwasi Trussonomics, distance the new PM and chancellor from it, and justify tax rises and spending cuts long in the making. The Brexit black hole is an economic reality that makes it all the weirder that our leaders seem to prefer to fall into it rather than fill it in. One thing I am sure of: the public are ahead of the politicians on this one and sooner rather than later will want to see serious, grown-up ways of filling the hole, rooted in a new, serious, grown-up relationship with the enormous market on our doorstep, to which we have raised so many self-inflicted barriers.

I mentioned last week that the CBI had asked me to speak at an event on mental health at their annual conference in Birmingham, another sign that business is taking this issue more seriously than government. I arrived in time for Keir Starmer’s speech and the Q&A that followed. It felt like something of a moment. The room was absolutely packed, every seat taken, dozens of delegates standing at the back and down the sides. The applause at the end was as sustained as any I can remember for a Labour leader, or indeed any leader. And one of the CBI top brass told me that by comparison with the response to Rishi Sunak a day earlier, “the applause was twice as long and three times as warm”.

Asked why, he said Sunak answered serious questions about labour market shortages that were worrying so many of the people in the room with “Tory HQ talking points about boats in the Channel.” I asked what Sunak’s main point had been. “Hard to discern,” was the answer.

Back in London, a few days later I interviewed former New Zealand prime minister Helen Clark, our latest guest on The Rest Is Politics. She had been in parliament for meetings and was in the gallery for prime minister’s questions for her first in-person our new PM. How did she find him? “Slight,” she replied. And I don’t think she was just talking about physicality.

Southwark Cathedral was a perfect setting for a fundraising dinner for the Tessa Jowell Foundation, which seeks to find better treatments and cures for the brain cancer that killed one of New Labour’s most popular ministers. Tessa’s daughter, Jess, runs the foundation and spoke movingly not just of her mum’s life and death, but of the progress being made in the fight.

My own daughter, Grace, has taken a very different route – comedy – and she and I did a double act in co-compering the evening. It meant that the speakers and attendees got some of the mickey-taking treatment more usually directed at me. “Most of my generation,” she said, “had never heard of our first speaker until his recent big break, when he was portrayed in the popular documentary series, The Crown… please welcome Tony Blair.”

I am writing this during another sofa-bound four-match working from home World Cup marathon. My partner, Fiona, who loves football about as much as I love having my nails painted or my legs waxed, will occasionally pop her head round the door, and mutter “what a life… watching football all day. I don’t know how you do it.”

I honestly don’t know how people don’t do it, when the opportunity exists to do it. My two-finger touch-typing means I can get so much work done, especially during the breaks in and between the matches. Prediction: it’s between France and Brazil.

Finally, may I add my own bit to this week’s Cantona celebration. I once asked his team-mate and room-mate, Peter Schmeichel, for his assessment of Eric. “I love his differentness,” he said. What a great word.

“Back then, everyone played more or less in the same way, 4-4-2, we worked in the same patterns. With Eric, even he didn’t know what precisely he was doing in the games. Therefore, our opponents had no chance of knowing.”