I got to know David Axelrod when we were both trying to help Ed Miliband defeat David Cameron in the 2015 general election. We failed.

But something Barack Obama’s strategist said at the time stuck with me, and I have thought of it often as the US presidential election nears, and with it the horrific prospect of a second Donald Trump term in the White House.

“The thing about conventional wisdoms in American politics,” he said as we sat around chatting one evening in between preparing Ed for a TV debate the next day, “is that they are almost always wrong.”

The conventional wisdom a few days ago was that Trump is nailed on for a return to the White House after the November 5 vote. That was despite a worse-than-average record during his term in office, a refusal to accept the outcome in 2020, the fuelling of a riot at the Capitol, the writing into the history books as the first holder of the office to become a convicted felon, pathological lying about himself and his opponents… none of it appeared to have shaken the sense of inevitability that he was heading back.

The New European’s brilliant front cover last week, “The bullet hit Trump, but it killed Joe Biden”, underlined a new, stronger conventional wisdom, that a failed assassination attempt, allied to Biden’s decline before our eyes, combined to turn probable into near certain, and so left me hoping against hope that Axelrod’s maxim is right.

The dramatic and almost deadly event should not have changed the fundamentals at all. But politics, and history, rarely operate in clear, straight lines. The post-shooting Trump is the same lying, manipulative narcissist who existed before the would-be assassin pulled the trigger. But the sense of him changed, the mood of his supporters changed, and the manipulative part of his makeup made sure to present himself as the more unifying figure he wrote into his convention speech a few days later.

It was, whether we like it or not, a game-changing moment. It shouldn’t have been, because for it to be so accords more significance to the shooter than he deserves, but it was. And game-changing moments are called game-changers for a reason.

If we look back at our own recent election, there were two game-changing events that helped push the Tories out, and one that got Labour in; namely Partygate under Boris Johnson, and the mini-budget under Liz Truss, the irrelevance of both ex-PMs plain for all to see in the paltry audiences they attracted as they sought to bathe in the Trump glow at the Republican convention in Milwaukee.

And there was one game-changing event on the Labour side, namely a change of leader, from Jeremy Corbyn to Keir Starmer.

The change alone was not sufficient to explain the result, however. Indeed, there was a time when the conventional wisdom around Starmer was that he couldn’t win. That one certainly fell victim to the wisdom of the Axelrod maxim. And that gives me hope that “Trump can’t lose” can now go the same way.

The US game-changer required has been obvious since Biden’s dreadful showing in the first TV debate. Now that it has happened, Donald Trump, for all the bluster, is less nailed on than he was. Allelujah.

Invited to speak to a group of largely American businessmen (and a small number of women,) I didn’t hold back in my take on Trump, and while there were nodding heads aplenty, I could sense others were far less sympathetic to my views. When it came to the Q&A, one man asked why we should expect America to continue to protect Europe’s security “when you show such disdain for us”. Another asked me to justify my statement that “Trump’s return represents a real threat to democracy in America and therefore democratic values everywhere”.

Questioner 1 had a point, and I admitted Europe had perhaps taken US defence protection for granted for too long, but explained that the disdain was very much for Trump and what he represented, not for the USA as a whole. But to questioner 2, I felt that even asking the question underlined the extent to which the normalisation of the abnormal had already happened.

For example, losers accepting the result of an election is a fundamental pillar of democracy. To his credit, Rishi Sunak has shown exactly how to do that. That Trump continued to peddle the big lie that the election was stolen, or that Biden was behind his legal troubles, were themselves attacks on a democracy founded in the notion that political leaders should seek to tell the truth.

Part of Trump’s skill as a politician is that he can be excused behaviour by his supporters that they would not tolerate in their children, their employees or themselves. It all suggests a body politic that has something a lot worse than Biden’s Covid.

The Diana Award honours young people who help others, and I was part of a panel to launch their report on young people’s disengagement from politics.

Amid the negativity, I did point out that we had just seen major change as a result of an election, and that the current parliament had the highest-ever proportion of women, ethnic minorities and LGBTQ+ MPs, plus the most state school-educated cabinet in history.

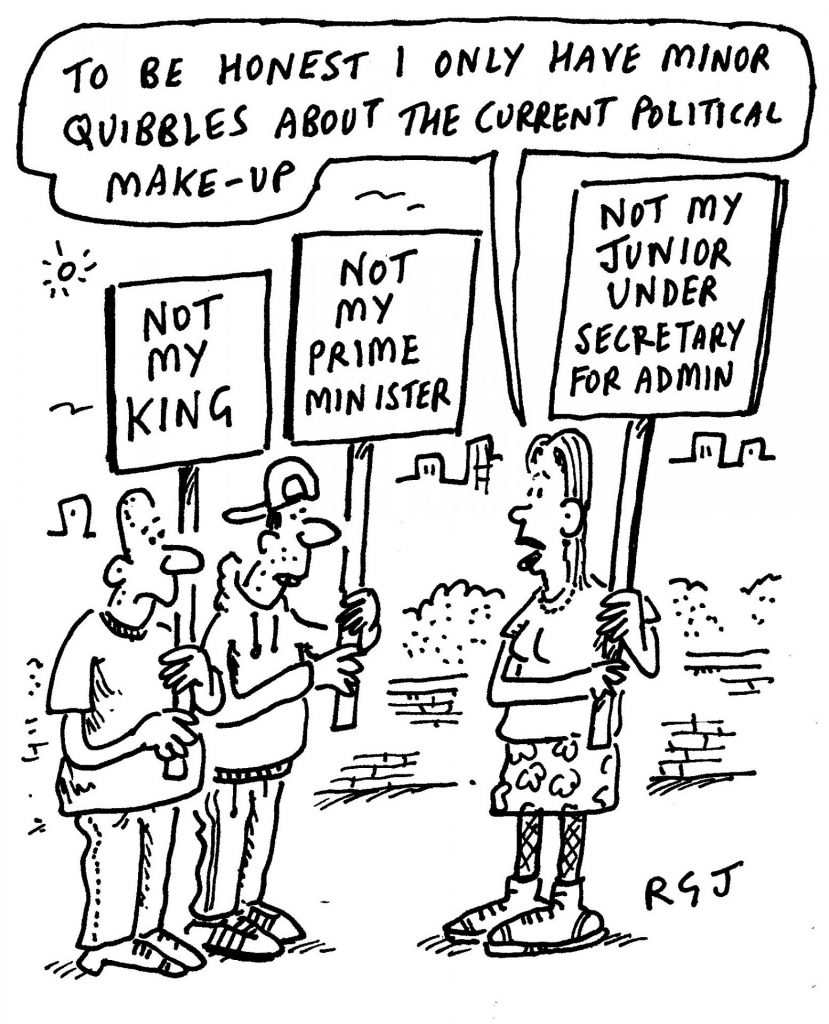

I said that while it was fine to bemoan lack of trust in politicians, it was incumbent upon all of us to reflect on what more we as individuals could do, that shouting from the sidelines was easy, but more good people had to step up and get involved.

I could see my fellow panellist, Liberal Democrat MP Sarah Olney, smiling, almost laughing, and when TV presenter Alex Beresford brought her in, I thought “Oh here we go, ‘who is he to talk about trust, given spin, Iraq, etc etc…’”

But no. She said she’d heard me say exactly the same thing on TV the day after the 2015 election, when the Liberal Democrats had been reduced to just eight MPs. “I thought he had a point, I should get more involved, and so the same day I joined the Lib Dems,” she said.

Within a year, she was a winning by-election candidate in Richmond Park, a seat she lost in 2017, then won back in 2019, and won again on July 4.

Of course, I would have loved it if she had been inspired to join Labour instead. But I was happy to have played a role in motivating her to get involved at all.

Blenheim Palace, a place I know only through past participation in the annual triathlon there, did look rather splendid as Keir Starmer hosted 40-plus leaders at the gathering of the European Political Community. Good weather always helps at these diplomatic shindigs, and so does a good mood, largely created by the clarity with which the Tory era of seeing Europe as foe rather than friend was buried.

The coverage around Europe was pretty large, and overwhelmingly positive. I still think Labour did not need to go so hard on ruling out membership of the customs union and the single market, but, as German TV’s Annette Dittert pointed out, an awful lot of diplomatic progress was made in a single day.