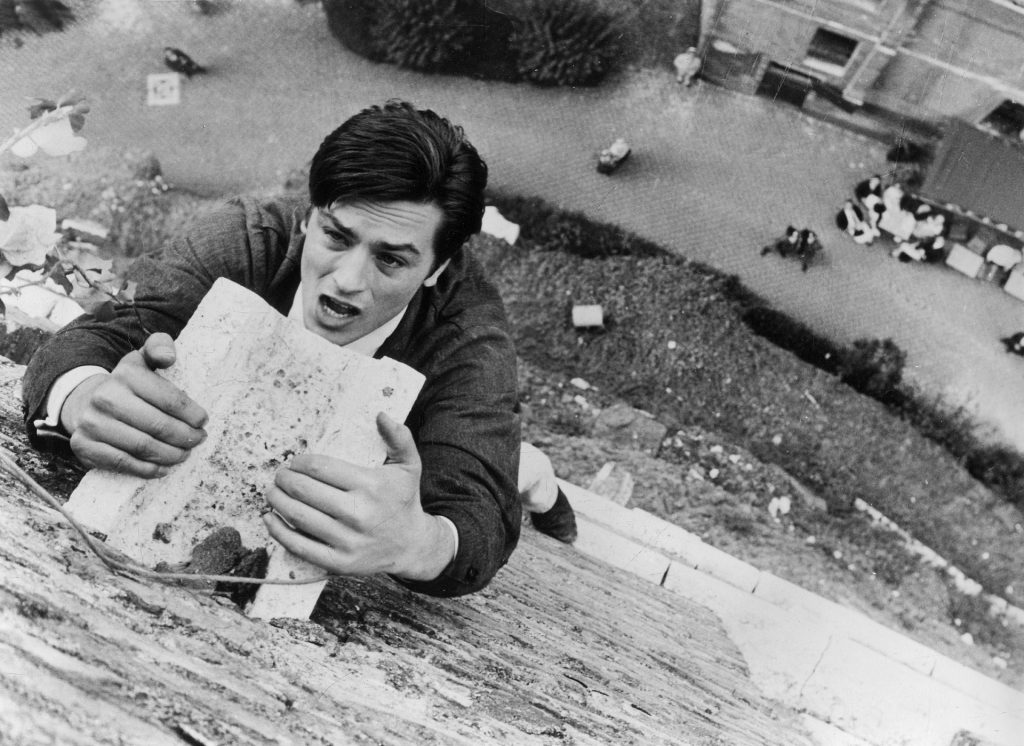

Alain Delon has made it home, and now it is time to let go. Mortally wounded at the end of L’Insoumis (1964), he collapses to the floor and lies on his back, staring up at the thing we will all see one day. His right hand is across his chest and for a moment his left comes to join it, before it passes over his face; a final act of covering his own eyes.

We’ve seen Delon die many times, in this and other films, and on countless glimpses of the cover of The Smiths’ 1986 album The Queen Is Dead. There he is in the closing moments of L’Insoumis, his hands together on his chest, a deep green tone covering the image. As Morrissey sings on the album’s I Know It’s Over, “Oh mother, I can feel the soil falling over my head.”

Of course there is another thing the actor and the singer have in common. In the aftermath of Delon’s departure, many will feel unable to separate his often magnificent art from his often malevolent actions and comments. Or to put it another way, as Morrissey wrote on his website on Sunday: “No doubt The Guardian will give him a glowing obituary, but if he continued to live in good health they would hiss and tell us that he is Far White (sic). When will they ever learn?”

If Delon was not on the far right towards the end of his life, he certainly gave a good portrayal of someone who was out there on the extreme. He cosied up to the revolting Jean-Marie Le Pen, praised the “uplifting” progress of the French National Front and said homosexual marriage was “against nature”.

But there is one thing that Morrissey got absolutely right about Delon: the power of his stillness. In his best films – among them Plein Soleil (1963), the first adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley, Le Samouraï (1967), La Piscine (1969) and Monsieur Klein (1976) – he transmits an otherworldly blankness that is insolent, dangerous, compelling. We’re left asking: What on earth is going on under there?

Was it Delon’s reaction to his own impossible beauty, so excessive that it was regularly described as “cruel”, that made him act like he did in films, and act like he did in life? That made him reject playing romantic leads in favour of playing inscrutable killers, that made him reject romantic partners and his own children in favour of life as a solitary man who described his favourite sound as the cry of a lone wolf in the night?

We can’t know, but we will keep asking every time we see him walking through the fish market in Plein Soleil, or adjusting his hat in the police line-up in Le Samouraï, or lying back with his hands over his chest on an album cover. He’s the still pool with our own reflection in it. Or as French novelist François Mauriac wrote of Alain Delon on the release of L’Insoumis: “He never speaks so well as when he’s silent.”