“We can’t look weak. If we don’t show up, we’ll look weak. We can’t look weak.” So said Donald Trump, as Michael Wolff reveals, after the attempt on his life at Butler, Pennsylvania, on July 13, 2024, when friends and advisers urged him to delay his arrival at the Republican National Convention.

In All or Nothing: How Trump Recaptured America (The Bridge Street Press) the fourth of his definitive sequence of books about the 45th and 47th president, Wolff describes a brutally Hobbesian world divided by strength and weakness and framed by confrontation: “Conflict made him feel alive, ready to go; it was his elixir.”

Since his inauguration on January 20, Trump has been moving, to borrow the phrase of his former adviser Steve Bannon, at “muzzle velocity”. At home, he has run roughshod over the law and the constitution. In his warp-speed attack on the international rules-based order, the president has capsized the Western alliance and, as the world watched, demeaned his office by berating Volodymyr Zelensky in the language of a mob boss (“You don’t have the cards!”).

So it is salutary to be reminded of the against-all-odds manner in which Trump came back from defeat and the rollercoaster ride that restored him to the White House. Wolff picks up the story after the 2020 election as the beaten Republican returns to Mar-a-Lago, floating in an impermeable bubble of denial.

“There was not the slightest indication,” he writes, “not the smallest opening of self-awareness, that he even sensed the enormity and finality of what had occurred… He showed no inclination for meaning in the events, or to sift the experience.”

How easy it is to forget that, as Joe Biden was inaugurated, “it was at best a loser’s fantasy that [Trump] could run for president again”. Disgraced by January 6, twice impeached, denied a second term: surely he was finished? When his son-in-law and former senior adviser, Jared Kushner, was asked about his future, he replied: “What was Nixon’s future?”

The great paradox of what happened next – explored with panache by Wolff – is that Trump was resurrected and empowered by the very campaign to destroy him. As the FBI raided his home looking for classified documents and the indictments began, the orthodoxy was that he was not only finished but headed for prison. In practice, however, this moment of maximum peril was also the moment of maximum opportunity, marking “the real beginning of the 2024 campaign”.

It was Trump’s instinctive genius to grasp immediately that his legal woes were not a distraction from his bid to regain the presidency but its very heart. Again and again, the contender declares: “Our legal strategy is our media strategy; our media strategy is our legal strategy”.

And so it proves. When, on August 24, 2023, he is indicted on racketeering charges in Fulton County Jail in Atlanta, Georgia, he understands that his mug shot is a global photo op as well as (in conventional understanding) a historic low for a former president.

As Wolff reveals: “He’d been practising it for days – on the golf course, in the mirror, in front of the legal team, and among Bedminster members”. Trump is delighted by the image.

“This looks so cool, this is a classic, this is iconic,” he says, as it is instantly plastered across mugs, T-shirts and other merchandise. Not for nothing does that picture now hang in a golden frame, just outside the Oval Office.

On May 30, 2024, Trump is found guilty on all 34 felony charges in the New York hush-money case. Catastrophe? Not a bit of it.

In the first six hours, his campaign raises $34 million; in 24 hours, $53 million. Absurdly, dementedly, but perhaps correctly, Trump declares the verdict “the best thing that ever happened”.

In Trump’s mind, even the prospect of prison can be reimagined as a mythical fate: “That’s actually pretty cool. I’m like Nelson Mandela. I’m ready, I’ll do fine, and you send me to jail. I’m guaranteed to be president”.

Everything, in his eyes, is cosmetic, superficial, defined by its surface. Along with strength and wealth, he values beauty. “I may not have the best legal team,” he says, “but I have the hottest.” As the author reflects: “Trump treated the people who worked for him very badly, except if you were very beautiful”.

In many ways, Wolff is the laureate of hyper-modernity: as an award-winning magazine writer, he understands that power in the 21st century is as likely to be found in celebrity, personality cults, the avaricious hoarding of attention and digital networks as in the formal institutions of state; that culture, psychology and the accidents of character matter more today than the formal processes of democracy.

Even now, a decade after he descended the golden escalator, the White House press corps reports Trump’s antics in a spirit of righteous bafflement, as though he were George Bush Sr or Mitt Romney having a protracted funny turn. But, since his first, best-selling book about the president, Fire and Fury (2018), Wolff has laid out a much more convincing road map; one that takes account not only of his subject’s manic idiosyncrasies and pathologies but of the broader cultural reasons for his successes (and failures).

More than once, he notes the astonishment of the Trump entourage that their boss never seems to “break character”. Is this because there is no true self to be disclosed? “All politicians compartmentalize, but this seems like something different.”

Which is both Trump’s fatal flaw – he has no inner life, no moral compass – and his political superpower: “Every other politician is finely repressed, carefully circumscribed, hidden behind protectors, full of secrets, a construct of public acceptability, but there on Truth Social every night, Trump is an open wound. What terrible turmoil one might assume he is internalizing – he isn’t.”

He oscillates wildly between childish insecurity and monomaniacal confidence, “his extraordinary personal world of certainty and inner-sanctum ease”. And the upshot of this is a confidence that performance and stagecraft are all that matter.

Enter Justin Caporale – now the president’s “executive producer” at the White House – who ensures that the stage, stunts and special effects are all in place before the candidate arrives. He builds sets that resemble the Oval Office for Trump’s press conferences: “His signage (the presidential seal had been rejigged to just this side of infringement) and production values had to be as good as those of any sitting president”.

In October 2024, when Biden appears to say that his opponent’s supporters are “garbage”, Caporale ensures that there is a Trump-branded rubbish truck on the tarmac at Green Bay airport in Wisconsin, ready for his boss to board for the cameras.

Everything is a show. Urged to visit the scenes of protest over the Gaza conflict at Columbia University, he recoils at the very suggestion: “No students! No students!” As he prepares for his fateful debate with Biden in Atlanta on June 27, 2024, he refuses to send out for food: “Sinatra told me once, ‘Never eat before a performance’.”

Even after a bullet grazes him at Butler, he refuses a CT scan, fearful that it will show “plaque” and people will say he has Alzheimer’s. Image is everything – as he has just shown by pumping his fist in the air and shouting “fight!”

The pen portrait of Caporale is one of many. Here is Elon Musk, about whom Trump is initially uncertain (“What the fuck is wrong with this guy? And why doesn’t his shirt fit?”).

Here is Boris Epshteyn, the permanently sycophantic lawyer who, somehow, retains his boss’s ear, and remains the “Trump quarterback”. And here is Natalie Harp, a young aide whose loyalty to her boss approaches derangement.

Carrying a miniprinter, she is never far from him, even on the golf course, holding his phone, running his social media accounts and curating the sheafs of paper in golden document clips that are his principal window onto the world.

Natalie writes him toe-curling letters of devotion: “I never want to bring you anything but joy. I’m sorry I lost my focus. You are all that matters to me. I don’t want to ever let you down. Thank you for being my Guardian and Protector in this life…”

Which would matter less if she were not, in effect, the main gatekeeper to the politician about to become, once again, the most powerful man in the world. Feeding him “uppers” of hagiography and “downers” of reported disloyalty, Natalie (incredibly) is “likely the single greatest influence on the candidate; his muse, his whisperer, his security blanket”. So great is her influence, that it becomes a matter of concern not only to his campaign officials, but his Secret Service detail.

If Natalie is always at Trump’s side, Melania is rarely close; remaining the riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. Long-time aide to both Trumps, Jason Miller, is despatched to seek her public support. “Nice try,” says the former (and future) First Lady. On election night, she sends word that she will not appear with her husband unless he has secured an outright win. According to one habitué of the Mar-a-Lago patio: “She fucking hates him”.

In Wolff’s telling, Trump is a seething cluster of appetites and impulses. “Bring me the poison,” he demands – a basket of Starbursts, Hershey’s Miniatures, Laffy Taffy and Tootsie Rolls.

In the break room in court, his lawyers have to put up not only with his outbursts (“I need you to be like Perry Mason”) but adopting his junk food diet: pizza, McDonald’s, Chick-fil-A, Jimmy John’s. Wherever he goes, there must be two quarts of strawberry vanilla ice cream.

Above all, Wolff’s book is an astringent corrective to those who still think that Trump is an ideologue, driven by deep conviction, with a settled blueprint he is determined to enact. Many of those he has appointed to senior posts do have such plans. But the president himself is supremely uninterested in policy.

Witness, for example, his fury when the Supreme Court overturns Roe v Wade in June 2022. This constitutional milestone had been – explicitly – the essence of the evangelical movement’s strategic decision to support him in 2016 and thereafter. He had dutifully appointed Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amey Coney Barrett to the highest court in the land.

Yet he cannot understand why the justices have done precisely what they had been selected to do. Their decision to roll back women’s reproductive rights is “a direct hit on his 2024 prospects – what were they thinking?”

Abortion becomes the toxic “A-word”. It is forbidden to discuss what might be the appropriate legal time limit. “Don’t talk weeks,” he insists. “Nobody talks weeks. Weeks get you into trouble. No weeks.”

No less petulant and solipsistic is his reaction to the horrors of October 7: “he’s always bored with Israeli-Palestinian dynamics… Now it’s a bigger story than he is.” Wolff continues: “At this moment, shaping up to be the worst day in Israel’s history, he’s full of annoyance at Israel and the Jews.”

Anything that denies him command of the news cycle is an affront – as Zelensky discovered last week, listening in disbelief as the president and JD Vance berated him in front of the world’s media. An unforgivable way to treat a war hero?

Yes, but in Trump’s summation: “This is going to be great television”. Who cares about the future of Ukraine and the integrity of the West when there are ratings to think about?

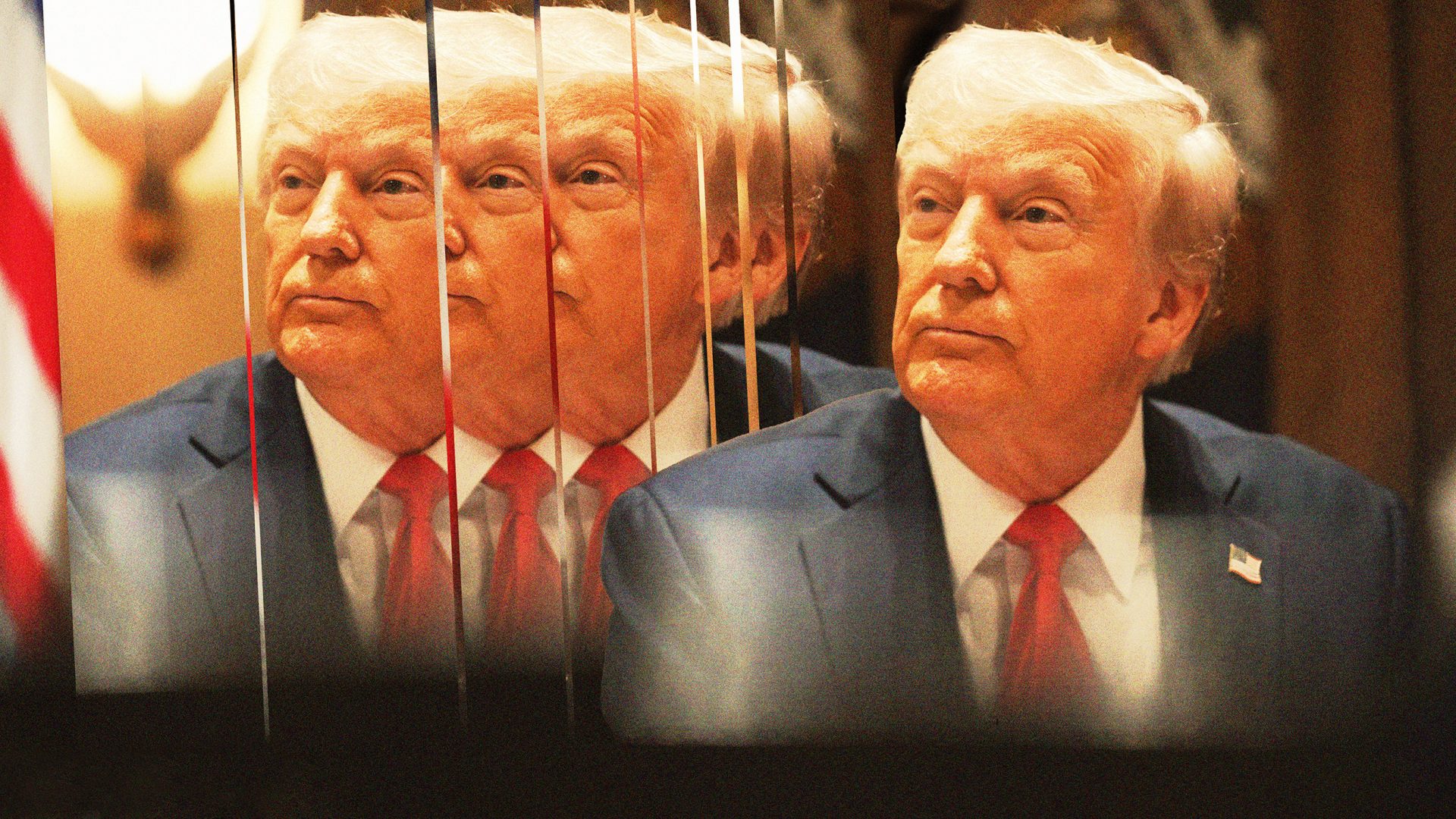

If there is any way to make sense of this, it is in the image used by his campaign of the “split screen”: what quantum scientists would call a multiple-state “superposition”.

Does Trump really believe that his terrible social media platform, Truth Social, is worth the billions that have been invested in it by the markets? Well: never underestimate “his magical, reality-denying capacity – that weird disconnect that was never to be discounted.” The laws of political and financial gravity? They’re for losers.

Wolff’s immensely readable account of this improbable chapter in Trump’s improbable career is, by definition, claustrophobic, a riot of compacted nerves: his is a Chekhov drama about a maniac in a chamber of gold, plastic and digital noise, surrounded by “a democracy of opportunists, grifters, and dunces”.

And now he is back on top of the world, returned from exile to inflict his derangement upon the whole planet. Let us hope there are more volumes to come from his most astute chronicler.

In the land of wolves -and many disoriented sheep – it is good to have a Wolff of our own, telling it how it is.