Whenever I am in Vienna I try to make a pilgrimage to the city’s vast Zentralfriedhof cemetery to visit a particular grave. It doesn’t belong to one of the great musical figures buried there, from Beethoven to Falco, Brahms to Edgar Froese – nor am I there to see other global figures like Arthur Schnitzler, Hedy Lamarr or GW Pabst.

Instead, I make my way to a grave tucked well away from the well-worn footpaths, in a secluded spot sheltered by trees, a black marble headstone with the occupant’s face emerging in bas-relief.

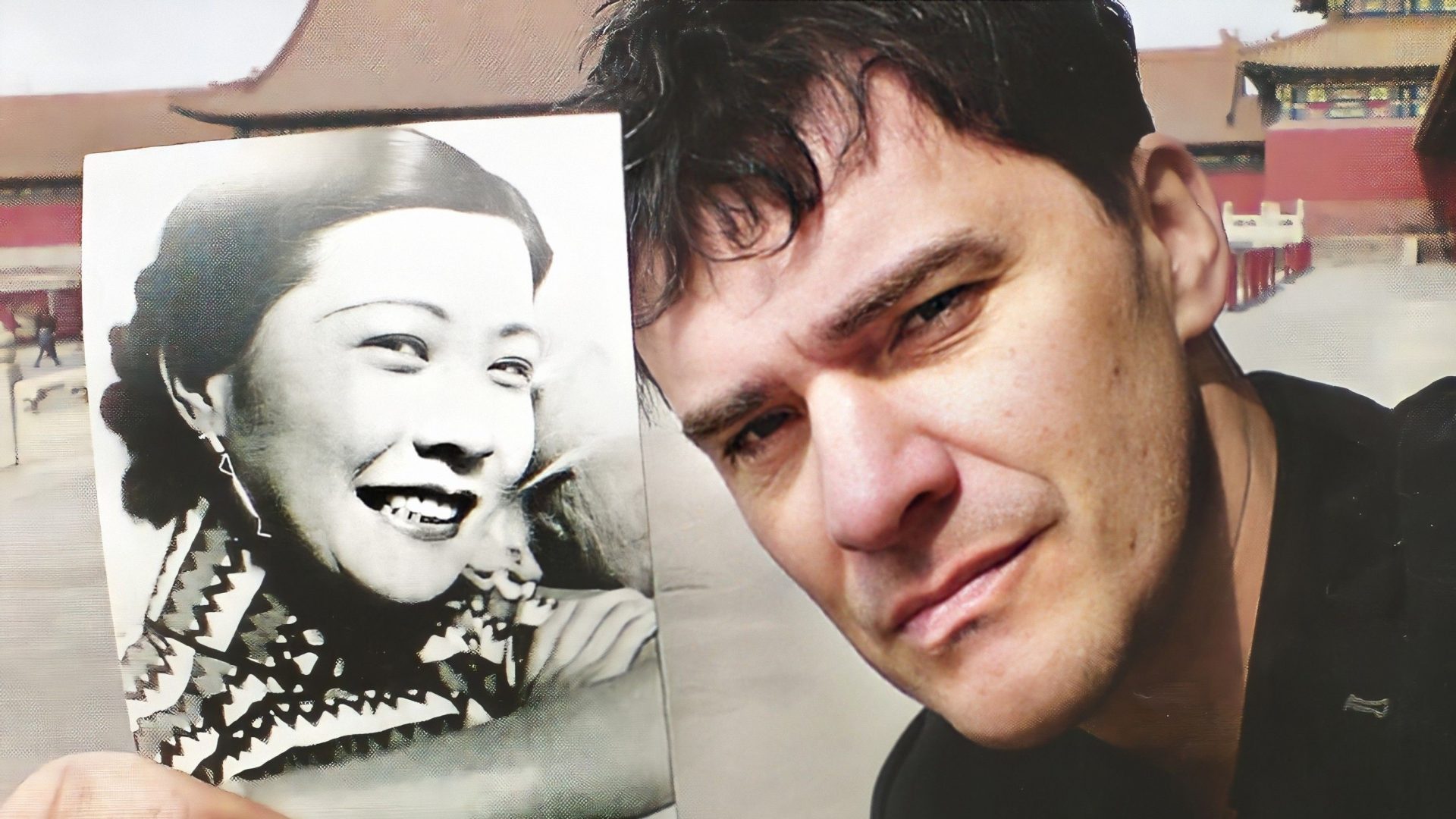

The face is that of Matthias Sindelar, one of the greatest footballers who ever lived. The star of the great Austrian national Wunderteam of the 1930s, Sindelar was a revolutionary centre-forward whose slight build and quick feet earned him the nickname of Der Papierene (the paper man) in recognition of how he flitted between lumbering defenders like a scrap of paper in the breeze.

He scored more than 600 goals in a shade over 700 appearances for Austria Vienna FC and won 43 caps for his country when the Austrians were widely acknowledged as the greatest team in the world.

Perhaps his most significant performance, however, came in a 1938 match in Vienna designed to celebrate that year’s Anschluss between Austria and Germany. The 35-year-old Sindelar captained the now ageing Austrians against a team assembled to showcase the superiority of the Germans in a last hurrah before the teams were combined into a side representing a greater Germany.

Despite rumoured threats and warnings as to what might happen if Austria had the temerity to score, let alone win, the veteran Sindelar led his side to a comfortable 2-0 victory, scoring one goal himself and creating the other. According to witnesses he celebrated both goals by dancing in front of the assembled Nazi dignitaries in the stand.

The match represented a considerable humiliation for the new regime, not least as Sindelar’s club side, Austria Vienna, which made up the bulk of the national side, was the team of the city’s Jewish community. Hence when Sindelar was found dead at home a few months later after a gas leak there were suspicions of foul play, although his death does appear to have been a tragic accident.

Aside from being one of the greatest players ever to pull on a pair of football boots, Sindelar represents for me the true spirit of Vienna. He came from a poor family, immigrants who relocated from Moravia to a working-class district of Vienna as part of a social stratum known as the “brick Czechs” for their labouring contribution to the local construction industry.

From these unpromising beginnings Sindelar became one of Vienna’s most popular and significant cultural figures, football being regarded in the city on the same cultural level as opera and the theatre. Football writers mingled with the art critics and philosophers who populated the city’s cafes around the Ringstrasse where Sindelar was a regular at the unofficial headquarters of Austria Vienna, the Parsifal Cafe, where he mingled with club officials and supporters, discussing tactics and prospects for upcoming matches.

This cultural elevation of the beautiful game meant that Sindelar’s elegant and skilful style of play inspired writers and poets as well as delighting the fans on the terraces. His obituary was written by the famous theatre critic Alfred Polgar, while one of Vienna’s leading literary lights, Friedrich Torberg, wrote a heartfelt elegy in verse called Death of a Footballer. The city came to a standstill for Sindelar’s funeral.

Yet for all his importance to the history of modern Vienna, Sindelar has been unfairly omitted from most histories of the period, a mere footballer considered unworthy alongside the likes of Schoenberg, Freud and Wittgenstein despite such cultural snobbery being the antithesis of the egalitarian foundation on which Vienna’s cultural and scientific legacy was built.

Hence when I picked up Richard Cockett’s Vienna: How the City of Ideas Created the Modern World, I confess I was cracking my knuckles ready to lambast another volume with a big Sindelar-shaped hole in its pages.

To my delight, however, not only does Sindelar appear in the book, but my Viennese hero drifts balletically into Cockett’s account as early as page 16, just one member of an enormous cast in an exhaustive but never exhausting account of a remarkable city at a remarkable time.

Writing any broad history of Vienna will always be a challenge because the city is so many different things, even today. Last year the Austrian capital regained its title as “the world’s most liveable city” in the annual survey conducted by the Economist. In addition to its cultural legacy, Vienna has a renowned public transport system for which an annual pass works out at a shade over €1 per day. Coal has almost been eliminated as a home heating fuel, with oil use down by 70% in the last 30 years. More than half of Viennese housing stock is publicly owned, meaning the city has avoided the housing crises and rent increases endured by citizens of other European capitals.

As well as its place at the centre of high culture, Vienna’s vast and strikingly designed public housing project Karl Marx Hof represents another side of the city’s successes, part of a concerted drive to solve a chronic housing crisis after the first world war. Around 64,000 flats were built in the first decade after the Armistice by the city’s “Red Vienna” administration, the first socialist regime ever to win at a European ballot box.

Cockett allows as much emphasis on this side of Vienna as he does in his coverage of its better-known, more tourist-friendly aspects. The book sometimes becomes a blizzard of names, some famous, some half-recognised and others new to even a Vienna-savvy reader, determined as Cockett is to tell as much of this remarkable story as space allows.

“In truth, no one who has looked closely can challenge the reality of Viennese influence across an astonishingly wide range of intellectual and cultural production,” he writes, “from nuclear fission to shopping malls, from psychoanalysis to the fitted kitchen.”

The roots of this extraordinary blossoming lie in the religious tolerance of the last Austro-Hungarian emperor, Franz-Josef, whose long reign fostered the ennui-riddled imperial nostalgia of later writers such as Joseph Roth and Stefan Zweig. Under Franz-Josef, Vienna became a city of immigrants, its population rising from 451,000 in 1857 to 2 million by the eve of the first world war.

They came from all over the crumbling empire: Silesia, Moravia, Bohemia and the wider German empire beyond, including the Moravian Sindelars (the footballer was born Matěj Šindelář). Vienna’s enormous Jewish legacy was fostered by this imperial tolerance, and by 1936 there were 180,000 Jews in the city, the largest urban population in Europe outside Warsaw and Budapest.

Underpinning all this was the concept of Bildung, the idea that developed in 18th-century Weimar and flourished in Vienna, which Cockett defines as “focusing on the personal growth of mind and spirit over the acquisition of wealth or worldly status”. Jewish society had always been scholarly, making the city and its population ideal bedfellows for the cultural, social and intellectual revolution that followed.

Cockett certainly does not duck the city’s dark side, either, pointing out that Hitler was formed largely by the time he spent in Vienna as a young man. The public housing projects, funded by high taxes, saw traditional landlords dispossessed, with many of them falling into the welcoming arms of a fascism also fuelled by an innate pan-Germanism that simmered in the city. A geographical class divide had developed, with the poor and working-class inhabiting districts on the fringes of the city outside the Ringstrasse, which acted almost as an unofficial border designed to foment division. There was also the influence of the vicious antisemite Karl Lueger, mayor of the city from 1897 until his death in 1910, recounted here in frightening detail, a man Cockett labels the first populist leader of the modern era.

Unvarnished though this account is, Vienna still serves as a fitting celebration of a unique city. If some passages can read a little drily, there is more than enough material to ensure the book never stops fizzing, from the rise of pioneering scientist turned Hollywood superstar Hedy Lamarr to how aspiring Viennese biologists and zoologists kept hundreds of species at home in their apartments, from insects to baby hippos, tigers and, in the case of experimental biologist Paul Kammerer, two huge American alligators.

It is one of travel writing’s most grievous cliches but Vienna truly is the ultimate city of contrasts, and remains so today. The far-right Freedom Party is flourishing and recent discussions as to the future of a 4.5m statue of Lueger that stands at the centre of a square bearing his name have led to a distinctly Viennese compromise this summer – the statue will be tilted 3.5 degrees to the right, the angle at which the human eye first detects something is amiss.

“This artistic approach raises questions and keeps them open,” said the jury appointed to the problem by the city council. “Through the slant, the statue’s claim to monumental status is broken.”

Perhaps appropriately, Lueger’s imminent list will represent almost a physical manifestation of Cockett’s assertion in this excellent book that “in the end the city crumbled under the weight of its own contradictions”.

Vienna: How the City of Ideas Created the Modern World by Richard Cockett is published on September 26 by Yale University Press, price £25