The high-water mark of ideological Thatcherism in the UK came between Nigel Lawson’s triumphalist 1988 budget, which – not long after the Conservatives’ third successive election victory – slashed the top rate of tax, and the introduction of the poll tax in 1990. Both have since been reversed, either suddenly or gradually – the poll tax didn’t survive Thatcher’s fall, while those on top incomes now mostly face average or marginal tax rates close to 1987 levels.

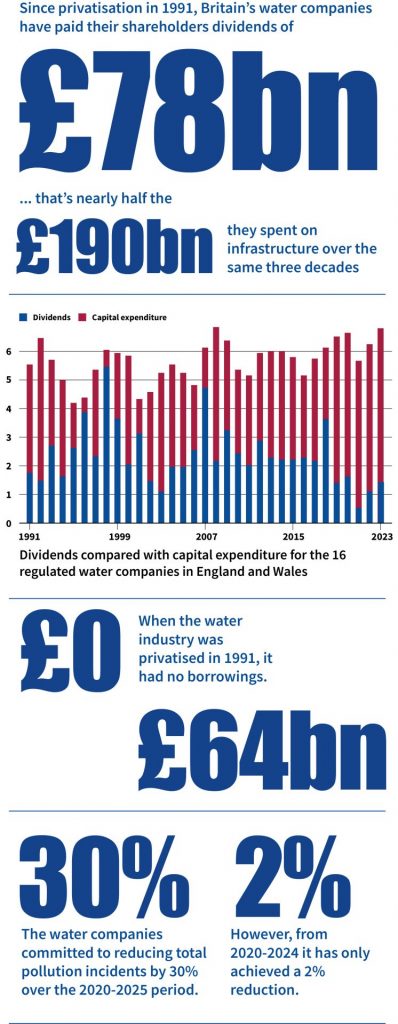

It’s odd then that one of Thatcher and Lawson’s most unpopular and unsuccessful policies – the privatisation of the water industry in England, which took place in 1989 – remains in place. How did we get it so wrong, and how did the regulatory framework put in place manage to achieve a remarkable trifecta – water companies teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, consumers outraged about bills, and environmental degradation and leaks?

Unfortunately, economics and economists must share some of the blame here. Like British Telecom and British Gas – but unlike other major privatisations of the Thatcher era, such as British Airways – nobody thought that you could just privatise a “natural monopoly” like the water industry without regulating the prices they could charge. Without that, they’d exploit their monopoly position.

And private ownership of natural monopolies wasn’t new. Power companies in the US usually had their profits fixed or capped by regulators.

When this worked well, it ensured that their returns were constrained to a reasonably low level, while at the same time making it relatively easy for them to raise capital from risk-averse investors, since the returns were in effect guaranteed by the state. However, there was one big disadvantage – with profits mostly fixed, regardless of how efficient the company was, there wasn’t much incentive to increase productivity or reduce costs.

The UK’s big innovation was “price cap regulation”. Instead of controlling profits, the regulators would fix prices in advance. As long as the private companies continued to deliver an acceptable service, any money they saved by higher productivity would feed into higher profits. Equally, if they messed up, shareholders would have to pay the price.

From an Economics 101 point of view, this seemed far preferable to a nationalised regime where the Treasury had to decide what level of spending and investment was required to deliver an acceptable level of service. It was also thought to be better than a US-style system, with little incentive for private companies to increase efficiency.

But it didn’t solve the problem that someone still had to decide what “acceptable service” looked like. And that was the regulators.

Ofwat was established to scrutinise the companies’ investment plans and work out what they “needed” to spend, and whether they were spending it. Meanwhile, the Environment Agency was supposed to ensure the companies met their environmental obligations.

They failed. Miserably. The Treasury was right that incentives mattered, and that the system they had introduced would give the new private companies much stronger ones. But it failed to perceive that while reducing costs would indeed increase profits, persuading, misleading and bullying the regulators would be even more lucrative.

So the water companies did just that, hiring a small army of expensive consultants and lawyers. Ofwat could never hope to match this onslaught, particularly since its more experienced and able employees could easily double or triple their salaries simply by switching sides and taking jobs in the sector that they regulated. So in the first decade of privatisation, as investment increased, bills went up, and so did profits.

Eventually that approach ran out of road, running up against a combination of a backlash against rising bills and the fact that even Ofwat could no longer ignore the level of excess profits. The regulator responded by restricting more severely how much they could spend and invest.

But, again, never underestimate the power of incentives. The companies turned to financial engineering to extract yet more money from the businesses; something Ofwat was even less well equipped to understand, let alone resist. In an era of low interest rates, the attraction of high returns, seemingly guaranteed by the companies’ ability to stay three steps ahead of Ofwat, was irresistible.

That too couldn’t last for ever. The combination of public outrage over the companies’ failure to meet even the most basic minimum standards with the recent rise in interest rates mean that the current regulatory model is both economically and politically bankrupt. The eye-catching, but ultimately superficial, reforms recently announced won’t change the underlying incentives much. Unfortunately – still constrained, 35 years on, by Treasury dogma – the government doesn’t seem to have realised it. We have not reached the end of this saga yet.

Jonathan Portes is professor of economics and public policy at the School of Politics & Economics of King’s College London, and a senior fellow at UK in a Changing Europe