The decision, when it came, fell somewhere between a plan and a whim.

In the mid-1970s Jeff Young was 17 years old and working as a filing clerk in a stupefyingly dull Liverpool office, the kind of place where “men disintegrated before your eyes”.

When one of those disintegrating men informed Young, approvingly, that he had secured a job for life, the teenager became terrifyingly aware of a future yawning ahead of him as an endless kaleidoscope of crushing ennui.

When he left the office that Friday afternoon, Jeff Young knew he was never going back. Instead, he was going to hitchhike to Paris and take things from there.

Most of us will have had similar teenage notions, of exchanging boredom for adventure, intoxicating ourselves with the excitement of elsewhere, of finding our tribe, of fulfilling the world-changing potential we knew brimmed to our eyeballs even if we had hitherto displayed no talent or ability at anything beyond a bit of huffy whingeing.

Then Monday morning would come around again and off we’d go to school, college or work, same as usual, ultimately reassured by our shackling to conformity because moaning and complaining are far less frightening than doing something, anything, different.

Jeff Young, meanwhile, did do something different. After a weekend spent listening to albums and flicking through books he believed would equip him with enough insight to slot easily into the rhythms of Parisian life, he was ready for this ambitious odyssey.

“And then when Monday comes,” he writes, “I get up at 7am to hitchhike to my imagined Paris of water lilies, bridges, absinthe, delinquent poets and the graveyard shrines of painters and rock stars.”

Young is probably best known as a radio dramatist and for his 2021 memoir of Liverpool childhood, Ghost Town, which was longlisted for the Costa prize for biography.

Wild Twin: Dream Maps of a Lost Soul and Drifter is a companion of sorts, a brilliant evocation of disaffected youth on a continent still processing the second world war as the first generation to emerge from industrial decline suspects it might all have been for nothing.

On the face of it, the half century-old travel anecdotes of a bored teenager might not sound like the most beguiling prospect on the bookshelf. Certainly, if we project our own teenage selves on to the idea it is a terrible one. Back then I had done nothing and knew nothing about anything while remaining convinced I knew everything: the key ingredients of an unbearable bore at any age, but particularly at 17.

Thankfully the insight of the half century that has passed since Young’s European adventures, aided by the journals he kept at the time and his luminous prose, make Wild Twin utterly absorbing, absolutely one of the best non-fiction titles of 2024. Not only an insightful journey in our continent, Wild Twin is also a thoughtful exploration of the illusions and subterfuges of that wily old trickster – memory.

“This is memory on a mangled cassette, faded, decaying, faltering. Sound and vision recordings of things that might have happened,” Young writes. “I am the Great Rememberer and yet the memories are full of flaws and errors.”

This acceptance of the pitfalls of recall combined with a deep reverence for the past elevate Wild Twin way above more conventional memoirs.

“I think of the past as being right here, right now,” he says. “I don’t understand when people say, you’re dwelling in the past, as if ‘The Past’ is elsewhere, somewhere negative, unworthy of attention, a place we should stop visiting.”

When that watershed Monday morning comes, Young is about to leave when his father returns from a night shift at the factory. The fledgling wanderer answers the inevitable question by confirming that no, he is not going to work. Indeed, he is hitchhiking to Paris.

There is a tiny pause before his father’s response. “Well, that’s a silly thing to do, isn’t it?”

Young sets out accompanied by his eccentric friend Stan, an aspiring comic book artist who “used to keep his nosebleeds in a jam jar” and it is clear from the start these are not seasoned travellers. Despite setting out for Paris, when they reach Dover they take a ferry not to Calais but to Ostend.

When they arrive in Belgium, Stan speaks for the first time since they left Liverpool to announce that he’s going home. Young’s journey will be made alone.

There are obvious comparisons to be made with Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts, in which the teenage author sets out across the changing Europe of the 1930s. Both journeys were recalled in middle age and were exercises in vagrant penury, sleeping in fields and barns and accepting the charity of strangers.

While Fermor’s odyssey is accompanied by an anthology of poetry and a public school education in the classics, however, Young is armed with Larry Niven’s 1974 science fiction epic The Mote in God’s Eye and a range of autodidactic cultural influences including Arthur Rimbaud, Patti Smith, Jack Kerouac, Anna Kavan, Lou Reed, Television’s Marquee Moon, Sun Ra and Amon Düül.

Indeed, early in the journey when he is aimless, grumpy and freezing in the bleak rural flatlands of Flanders, it’s literature that takes the blame for his predicament. “If someone stopped and asked me why I’m lost in the middle of Belgium and potentially dying of hypothermia in the middle of a field, my honest – and ridiculous – answer would be, flights of great lyrical beauty in a Picador paperback.”

Young is particularly adept at conjuring the whirl of whimsy, vulnerability and invincibility that protects us through our adolescence. While he frequently describes crying himself to sleep, sometimes in a field, sometimes in a hostel bunk, the feeling that the world has his back thrums beneath every decision, journey and situation, however potentially dangerous they might be.

We are so full of life at that age, whether conscious of it or not, that its burgeoning stock spills into a future we cannot comprehend ever being curtailed. Possibility is infinite because life is infinite, a feeling whose recollection from the cynicism of adulthood is as magnificent as it is frighteningly innocent.

“Innocence” is a strange word to attach to Young’s European adventure because the world he travels through is anything but. Some Belgian thinking about Albert Camus’s The Fall leads to a forsaking of Paris in favour of Amsterdam, arriving in a city where the tide of countercultural history has washed the last of the hippies, space cadets, freaks and weirdos, the sunset after the twilight of the 1960s identified by Danny the dealer in Withnail and I when he laments how “they’re selling hippie wigs in Woolworths, man”.

Young’s Amsterdam is a city of squats and squalor away from the tourist trail as idealism is slowly giving way to a simmering discontent in the age of Baader Meinhof, the Symbionese Liberation Army and Patty Hearst. Young, oblivious, still slots quickly into the rhythms of the city.

There is a brief sojourn to Paris where, like George Orwell before him, he eases into the underbelly of the French capital, drawn to the societal casualties and misfits in the alleyways and closes, the nooks and crannies that lead away from the Parisian mainstream. He stays in a grim hotel, inhabiting a room among the eaves with old newspaper for a carpet near a toilet so disgusting he cannot bring himself to use it.

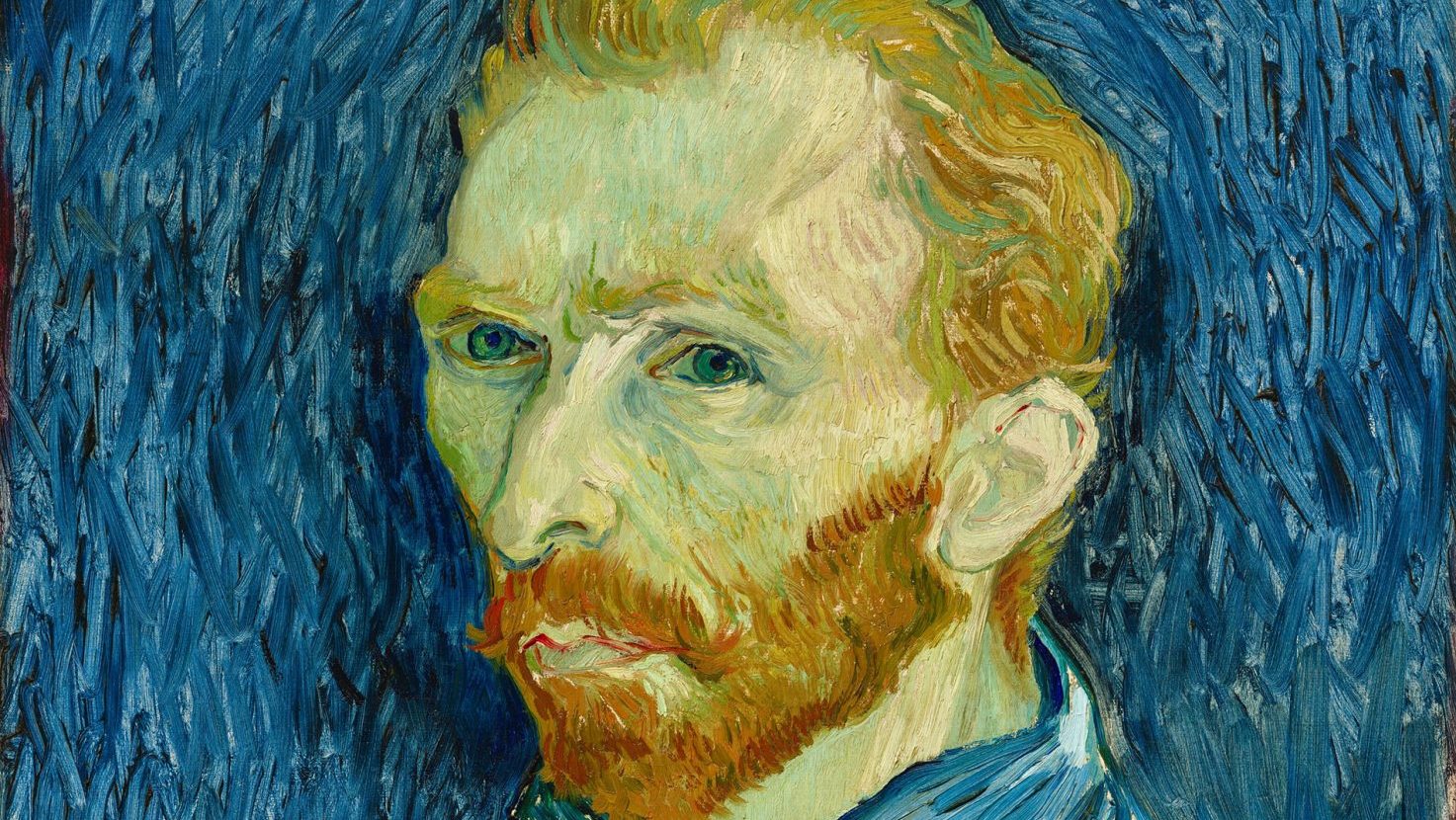

But, in one of the book’s key strengths, he still finds beauty even in seedy surroundings. Lying on his flea-ridden bed covered in itchy, blotchy bedbug bites, eating bread and oranges, he senses magic. “But just look at the view across the rooftops,” he writes, “it keeps making me cry. Dreams arise from dust, through the window the sky is full of lovers, men and women dancing in the heavens, dreams painted by Marc Chagall.”

His curiosity never fades. Pacing the streets to pass the time and keep warm he appreciates “the mystery of the next corner, that’s what keeps me walking. Every time I turn, a new city reveals itself”.

Eventually he is drawn back to Amsterdam, this time accompanied by a girlfriend, and moves into a squat with a traumatised insomniac called Bill the Wolf, a mysterious Belgian former mercenary and the malevolent presence of a drug dealer and his semi-captive girlfriend lurking in the attic.

This rodent-infested dive with no electricity in a twilight world of cash-in-hand menial work and occasional larceny inhabited by damaged refugees escaping who-knows-what could make relentlessly grim reading, but Young infuses his prose with beauty through natural empathy in “this shadow city, this phantom plane, this secret drift of the disappeared and invisible, this off the record, outlaw, Gastarbeiter, subterrain”.

His Europe is a hinterland of “English skivers, French and Swiss petty criminals hiding out from arrest warrants, dope-heads, remand absconders, scavengers, veteran anarchists, Zen anarchists, bullshit anarchists”, but all are sketched affectionately with a mixture of honesty and humanity that is beyond most writers.

One senses an undercurrent of grief underpinning the narrative, and the final section of the book is where that grief emerges. I won’t spoil things by revealing its source here, but it throws Young’s assertion at the start of his journey that “to become invisible is what I want most, the dream of disappearing” into heartbreakingly sharp relief.

There is much loss in Wild Twin, of youth, time, place and people, but kindness warms every page; the kindness of strangers he meets who give willingly when they’ve little to give and a deeper, more complex strain that grows into Wild Twin’s deeply affecting final pages.

“Nostalgia is an illness, perhaps,” he writes. “And yet, it’s beautiful.”

The past forms us, makes us who we are, shapes the different people we become as we pass through each phase of our lives. The ability to appreciate the past, to accept and revisit it, is vital because the past is life itself, it is who we are.

After all, if we cannot remember, what use is there in living at all?

Wild Twin: Dream Maps of a Lost Soul and Drifter by Jeff Young is published by Little Toller Books on September 18, price £20