Britain is rather rich in regional dialects, though not nearly as rich as many other countries in Europe, such as Norway and Switzerland. And these riches are not as plentiful as they used to be, before the Industrial Revolution and urbanisation. But there is still considerable interest today in local dialects of English, Welsh, Scots and Gaelic.

As far as English is concerned, a favourite activity of enthusiasts for this dialect diversity is the compilation of lists of dialect words from their local area. It is a simple matter to find references on the internet to numerous publications with titles such as A Dictionary of Essex/Suffolk Words and Phrases, A Cumbrian Dictionary, Nottinghamshire Words and Dialect Words from North Somerset.

But how do people know if a word is really dialectal or not?

It turns out that the answer is that very often they don’t. If you consult lists of regional words compiled by local amateur dialectologists in different parts of England, you can see that they not infrequently contain words which are not really local or dialectal at all. Some of the words which crop up in such lists – like spud “potato”, or bog “toilet” – are simply ubiquitous, informal colloquial forms of the sort that are frequently referred to as “slang”.

Other supposedly dialectal words could more accurately be described as archaisms: they are simply retentions of usages which have died out in General English but happen to have survived, for the time being, in the speech of some older people all over the country, for example to allow “admit”, nigh “near”, forenoon “morning”, howsomever “however”, happed “happened”, and vexed “distressed”.

Others are words which, again, do not belong to any particular area but are known only to people who have worked in or who grew up close to the older pre-mechanised agricultural world, and are therefore unknown to modern townspeople and members of the younger generations. This would include words such as headland “strip of land left for access at the end of a ploughed field”; hogget “sheep in its second year”; hames “pieces of wood or metal placed over, fastened to, or forming, the collar of a draught horse”.

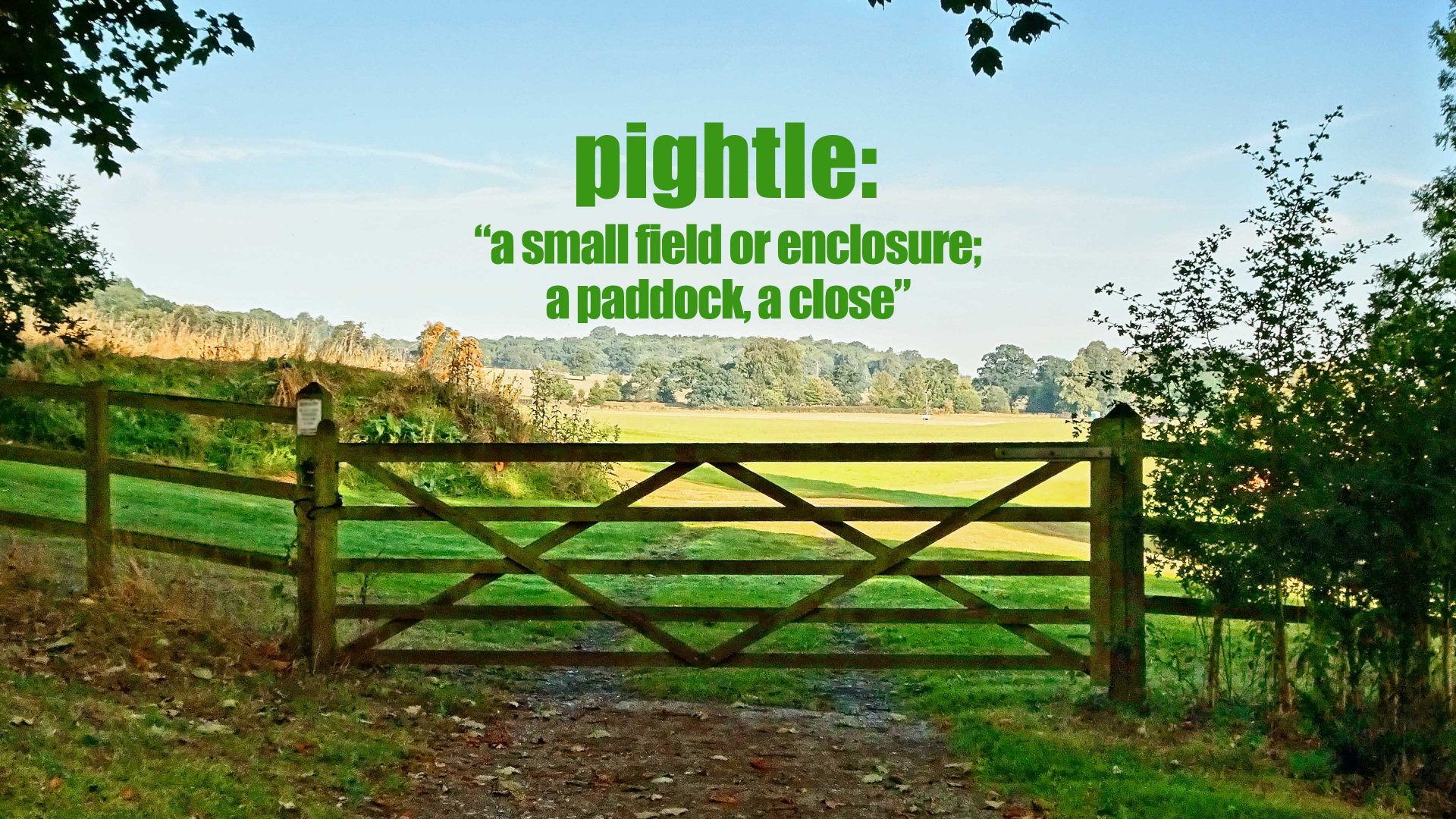

Pightle is another good example of this phenomenon. “The Pightle” has in recent years become rather popular in England as a name for a house, property or lane. It has the romantic ring to it of traditional rural dialect authenticity, even for the large numbers of people who have no idea what it means. (It actually means “a small field or enclosure; a paddock, a close”.) But which dialect does it come from?

We know the answer to this question, because The English Dialect Dictionary tells us. The word pightle is found in the “North Country”, the “South Country”, “East Anglia”, Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Rutland, Huntingdonshire, Hampshire, Yorkshire, Lancashire, Essex, Berkshire, Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire – and even the USA. Other dialect sources show it as also occurring in Somerset, Devon and Wiltshire. So even if that is not absolutely everywhere in England, it is very close.

Pightle, that is to say, is not really a regional dialect word at all; it is just a word that is used almost everywhere in the country but which most city people have never come across.

PIGHTLE

It is possible that pightle is much more of a regional word in North America than it is in England. The Dictionary of American Regional English shows that pightle is used in Long Island and other areas of New York State. It shows no records of it occurring anywhere else.