As is its way of doing things, the British government recently published the census returns from a century ago. On the evening of June 19, 1921, the inhabitants of Highclere were duly at their home. There was the fifth Earl of Carnarvon, George Herbert, together with his wife and daughter. Nowadays Highclere is better known as the setting for Downton Abbey, so it is no surprise to find that the servants of the earl were also at their posts that day.

Among the visitors on that occasion was a man named Howard Carter, from Swaffham in Norfolk. His occupation is listed as “painter”. This was Carter’s original profession, and it first got him invited to Egypt to record the scenes on the walls of the tombs. Anyone owning one of his watercolours today is fortunate indeed. They are valuable because they are good – and also because they were painted by the most famous discoverer in the history of Egyptology.

When I was 14, as a schoolboy keen on everything to do with Egypt, I met a rather distinguished but eccentric lady who turned out to have known Carter. It felt natural for me to ask her what the great excavator had been like. Her reply came without any hesitation: “He was a slug.” The British establishment did not quite take to Carter, and he was never at ease with the aristocrats, who were keen to employ him for his technical skills but not his personality.

In Egypt, he had a history of picking fights with bureaucrats, and this was especially true during his career in archaeology. The Egyptian antiquities service was run by the French, in a sort of cultural counterweight to British political control of the country. Things were particularly awkward with the head of the service, Pierre Lacau, whose patriarchal bearing and white beard earned him the nickname Dieu le Père. Here, the resentment was mutual. Lacau knew how to polish the chip on Carter’s shoulder. Nor was the prickliness confined to antiquities. There were reports that the provincial sketcher was the sort who could be rude to waiters. Carter was simply not a gentleman.

On November 4, 1922, the first stone step was unearthed in a remote corner of the Valley of the Kings, which led to the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. The tomb’s seal was officially broken on November 26, once Lord Carnarvon, the patron of the expedition, had arrived in Luxor. This guaranteed Carter the celebrity that came with such a sensational find. He was feted around the world and academic citations came his way. But he was never given an honour by the British government, and it is impossible not to wonder why. His personality may have gone against him, and his private life is essentially a blank, but that in itself does not account for the snub.

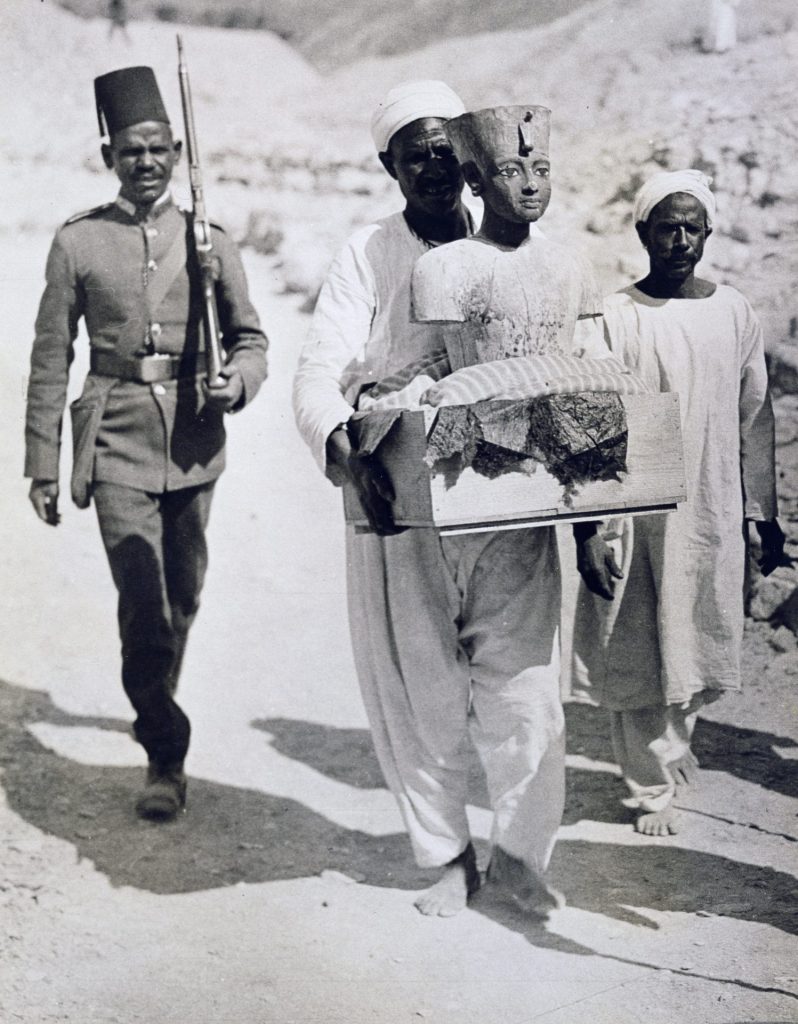

From time to time the rumour resurfaces suggesting that Carter helped himself to some of the contents of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber. The law in Egypt in the early 1920s was different from current rules. At that time, discoveries were divided between the Egyptian authorities and the excavators. Carnarvon had invested large sums into Egyptology over the years, and he would have felt entitled to a return on his investment.

In the case of Tutankhamun, the Egyptian government, which was restless after winning a new degree of independence from Britain, decided to move the goalposts in the middle of the game. Legislation was passed giving Egypt ownership of the entire find. It is hard to disagree with the idea that the contents of such a discovery should remain together in perpetuity, and nowadays the right of Egypt to own these treasures is never disputed. But it was not unusual for excavators at that time to deal in antiquities as a way of covering their expenses, and Carter was no exception.

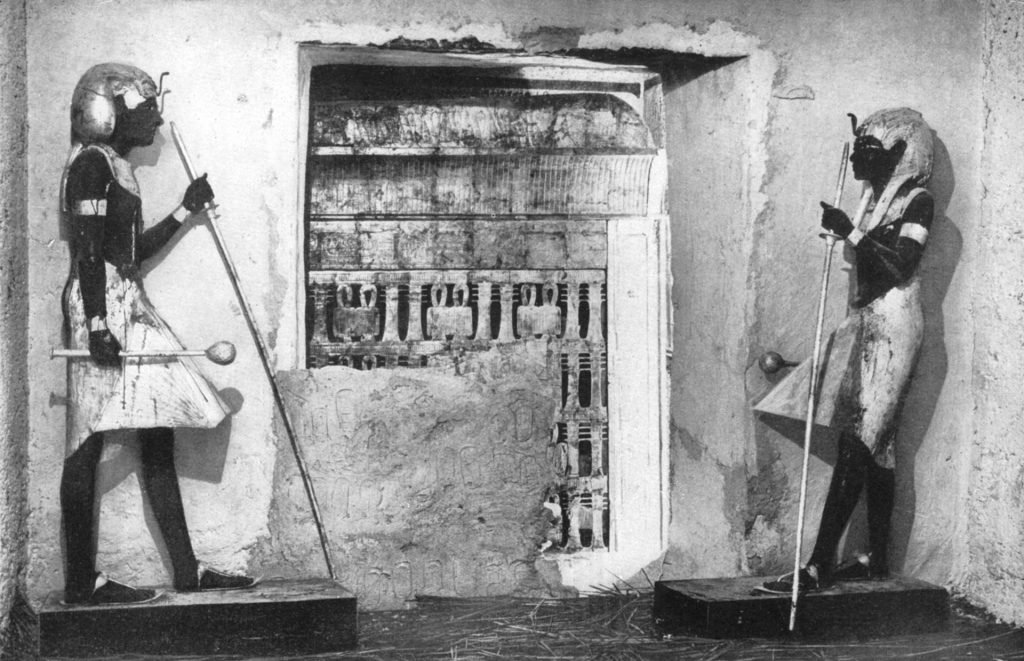

It seems very likely that Carter and some of his team quietly entered the sealed burial chamber of the king before the official opening in front of the world’s press. If there had turned out to be nothing behind that wall, the anticlimax would have been a fiasco. An informal rehearsal for this unveiling ceremony was a necessary precaution.

As it happened, the tomb was found to contain more than 5,000 objects, many of them small and some of them duplicates. Would a few have been missed? Some of Carter’s colleagues suspected that something like this had happened, and such rumours do not easily go away.

Tutankhamun, the boy king in his coffin and golden mask, was discovered within four years of the ending of a war that had devastated Europe. A generation of young men had lost their lives, and whole regimes had been swept away. It soon became clear that the pharaoh had died around the age of 18, which was also true of many in that lost generation.

An obvious example is the son of the poet and storyteller Rudyard Kipling, John, who had been that age when he was killed at the battle of Loos. Carter and Carnarvon had made a unique discovery, but there was tragedy at the heart of it. Many people in Europe who had lost loved ones turned to seances, spiritualism and cults such as theosophy. Many among the living were looking for the dead. Did this young king, who had emerged into the light after millennia in the dark, have a message for these grieving survivors?

It is against this background that the story of the Curse of Tutankhamun took shape. Carter and his co-workers had a huge problem with their work. They were in a confined space, conserving, clearing, and meticulously keeping records, all within the limits of a short season. Distinguished visitors soon became a plague, and the world’s press also wanted to be there.

As a result, Carter decided to give exclusive rights of access to the tomb to the Times. This made sense scientifically, but it led to a diplomatic outcry from the Egyptian government, which felt Egypt’s press was being sidelined. It also added to frustration among the reporters working for other newspapers who found themselves stuck in the hotels of Luxor, in the embarrassing situation of being all dressed up with nowhere to go.

Among these journalists were the travel writer HV Morton and the Egyptologist Arthur Weigall, who had been given a contract by the Daily Mail. Weigall did not invent the story of the curse, which had grown up as part of the gossip in Luxor’s bars, but he recognised a way of selling newspapers when he heard one. He was also a superb writer, and that helped. The story gained traction immeasurably after the sudden death of Lord Carnarvon from an infected mosquito bite. This happened just as Tutankhamun mania was reaching its peak.

Even now, the curse has its adherents. The number of people who are said to have been present at the opening of that tiny tomb-chamber in 1922 would probably fill the Albert Hall for an entire Proms season. Some years ago, it was announced that yet one more of these privileged onlookers had died, though by that time he was well into his 80s. The headline in the local paper duly ran: “Curse of The Pharaohs Claims Another Victim”.

This was not just random fantasy, because there is a reason behind this sort of thinking. Archaeology is intrusive, and sometimes it cannot fail to be destructive. In the Valley of the Kings the modern world was seen to be poking around inside a sanctuary where it had little or no right to be. The king at the heart of that resting place might not have been happy at having his peace disturbed. Would he turn to revenge? My grandmother was in her early 40s at the time Tutankhamun was taking over the world’s media. I remember her saying years later, when I talked about the discovery with her, “They should have let him rest.”

A similar unease surrounds the story of Tutankhamun’s trumpet. This was one of the many treasures of the tomb that found its way to the Cairo Museum. There, the decision was made to fit it with a modern mouthpiece, and play it over the radio, whereupon it was billed as the only sound that had ever reached us from the ancient world. This was in 1939. The rather eerie recording went out into the ether, and it was not long before some people convinced themselves it must have been this sound that set off the second world war. This theory had the effect of sidelining an alternative one about the war’s origins, which involved an Austrian with a moustache.

Tutankhamun entered the modern world in the middle of the roaring 1920s. It was time to turn one’s back on the first world war. The young king found himself right at the heart of Egyptomania. The designs of many of his objects fed readily into the stream of art deco, extending from exotic earrings and grandiose architecture to cigarette packets.

King Tut, as he soon became known, was now available for endorsing brands. Best-selling songs were written about him. Hollywood took to making films about pyramid-building and vengeful mummies. In London, there were jokes about the excavation of Tooting Common. Music hall acts began to involve talking sphinxes, sand dances, camels and no end of asp-waving.

Some years ago I went with some American colleagues on a trip from California to Oregon. One morning we drove into the town of Klamath Falls. There on a corner was a gigantic cinema set out in full Sunset Boulevard Egyptian decor, except that it was in the middle of the Pacific West. Tutankhamun’s shadow stretches a long way.

In a sense, the discovery of Tutankhamun was one of the byproducts of the British empire. But that is gone, along with Nineveh and Tyre, but few people today would regard it as a purely British achievement. Many of Carter’s collaborators were American, and the manual labour was done by the workmen of Luxor and their families.

It is clear the boy king’s real home has always been by the Nile. His treasures remain in Egypt, where they were recently moved into a spacious new museum. His body continues to rest in the Valley of the Kings. Otherwise, his belongings are kept together, except when some are picked to go on yet another global tour. This earns useful money for the Egyptian government, but it also introduces new audiences in their millions to one of the greatest achievements of the ancient world.

This year sees not only the centenary of Tutankhamun but also the 200th anniversary of the decipherment of hieroglyphs. Here the key instrument in our understanding turned out to be the Rosetta Stone. The date of the decipherment of hieroglyphs, 1822, is telling. Egyptology is an early 19th-century offspring of the Romantic movement. Here is the source of much of its glamour: sun kings, hippopotamus-headed gods,

and the mystic Orient are essential parts of its appeal. There are times when ancient Egypt seems to resemble us, but there are others when it is close to incomprehensible.

Equally, there are times when it seems that the study of ancient Egypt really is under something of a curse, a lasting impediment that prevents its followers from averting their gaze from solid gold coffins or losing a love of the macabre. This can make enemies for the subject. Some of the more sober branches of archaeology can be forgiven for thinking that Egyptology is obsessed with bling and the cult of celebrity. There may be an element of jealousy here.

When you have spent an entire season excavating and discovered nothing but an olive stone, you may look at the contents of King Tut’s tomb and decide that life is being unfair. But the disgruntled dirt-diggers have a point. Egyptology can sometimes seem like little more than bombast, and much of this can be traced back to the hype surrounding Tutankhamun. His legacy to scholarship has not always been beneficial.

Perhaps the lasting impression given by the tomb of Tutankhamun is not the glamour, or the controversies it has aroused. If we are honest, the purely historical information the find has given us is disappointing. The point of it all lies in the small touches of humanity it has preserved.

There are smudged fingerprints on several of the jars, and some of the toys seem to have been broken by excited children. In the dust on the floor were the footprints of the last people to leave the tomb, 33 centuries before. The young king collected walking sticks, and there are indications he was lame. He owned an ivory writing palette, with pens and ink, which seems to have been a gift from one of his half-sisters, Meritaten.

The excavators also found a small container among the teenager’s belongings. Inside this was a pendant, a golden figurine of the pharaoh Amenhotep III, who had ruled New-Kingdom Egypt at the height of its imperial glory. He was Tutankhamun’s grandfather. Also in the box was a lock of reddish hair, with a label saying that it had belonged to the boy’s grandmother, Queen Tiye. Some decades later, Egyptologists in Cairo decided to take a look at an anonymous mummy found years before in the Valley of the Kings. Time and tomb robbers had taken away anything that could identify this woman’s body.

The position of her arms showed she had been buried as a queen, and her generally regal look fitted well with that idea. They took a sample of her hair, still long and flowing, and compared it with the lock preserved in the tomb of Tutankhamun. The match was exact; the mystery lady was Tiye. We were able to recover this thanks to a small keepsake her grandson had chosen to take with him into eternity.

John Ray is emeritus professor of Egyptology at the University of Cambridge. His book The Rosetta Stone and the Rebirth of Ancient Egypt is published by Profile Books