Well, somehow we’ve got through another 12 months on this godforsaken lump of spinning space rock swinging around its dying star. Fair to say this has not exactly been a vintage year for our particular godforsaken lump of spinning space rock so thank goodness we’ve had books to distract us, energise us and offer a welcome refuge from the nonsense.

Elon Musk can’t change the algorithm to insert crackpot conspiracies and racists into the book you’re reading, nor can Gregg Wallace pop up between chapters to whinge about middle-class women of a certain age, so there’s that, at least. Let’s take the positives where we can find them.

This is the time of year when I’m asked whether this has been a good year for books, to which I unfailingly clap the inquisitor on the shoulder and inform them heartily that, my dear old thing, every year is a good year for books because every year a whole load of brilliant books are published. These are accompanied by some good ones, indifferent ones and a fair few absolute stinkers, but if you’ve reached this point in the annual go-around thinking it has been a bad year for books you have just been choosing the wrong books.

Indeed, here are a few you might have missed because, as is customary when we reach December, it is time to cast an eye back over the previous dozen months and pick out a few highlights. Inevitably this is a subjective exercise; there will be tomes mentioned here you might disagree with seeing included in an end-of-year “best of” round-up, likewise you will probably reel off a fair few titles that I haven’t mentioned. Do let me know which books you’ve enjoyed and would recommend instead.

Our yuletide hootenanny of literary high-fives comes in two parts: next week we’ll be rummaging through the fiction highlights of 2024, while this week we’ll focus on the pick of the non-fiction titles.

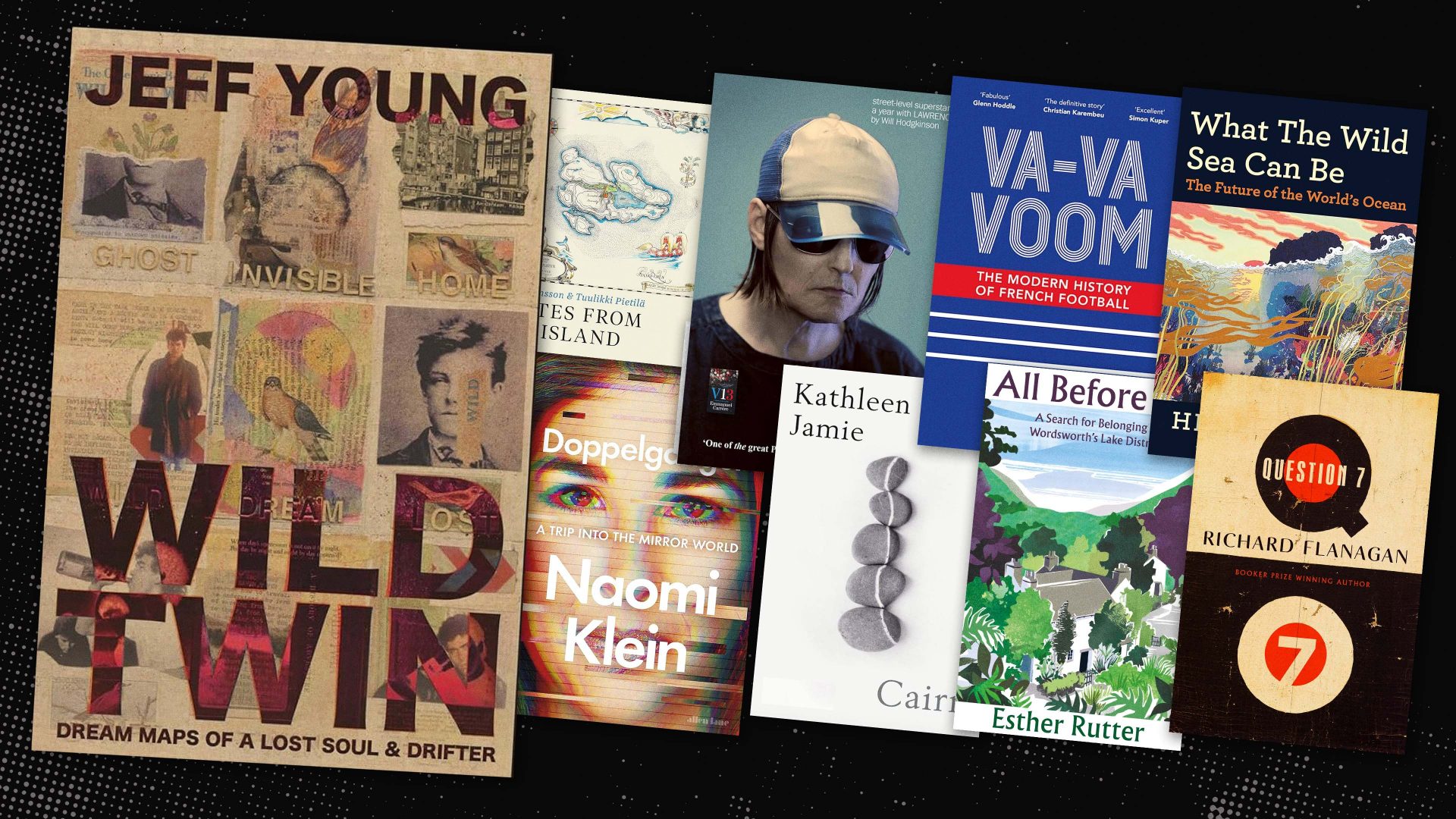

First up, a look at the major prize-winners. The Baillie Gifford Prize is arguably the Booker of non-fiction and this year it was won by Richard Flanagan with Question 7 (Chatto & Windus, £18.99), an extraordinary book that combines memoir, history and autofiction to encompass topics as disparate as Flanagan’s father working as a slave labourer near Hiroshima when the bomb was dropped and HG Wells and Rebecca West’s love affair. Flanagan won the Booker in 2014 for his novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North so has now completed an impressive double.

This year saw the first-ever Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction awarded, overdue and very welcome, which went deservedly to Naomi Klein for her absolutely banging exploration of being persistently confused with Naomi Wolf and what that tells us about modern discourse, Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World (Penguin, £10.99).

At the British Book Awards the gong for narrative non-fiction went to Rory Stewart for his popular memoir Politics on the Edge (Vintage, £10.99), while the non-fiction lifestyle award was picked up by GT Karber for his startlingly successful Cluedo/Sudoku crossover Murdle (Profile, £14.99).

Casting the net wider than the gong-clutchers, let’s begin with Emmanuel Carrère’s V13: Chronicle of a Trial (trans. John Lambert, Fern Press, £20). V13 is the deepest of dives into the trial of the 14 people plus abortive suicide bomber Salah Abdeslam behind the Paris terror attacks of 2015, taking its title from the date Vendredi 13 Novembre.

Carrère attended every moment of the 10-month trial while covering the proceedings for a French magazine and this translated collection of his columns is a nuanced and wide-ranging exploration of the best and worst of humanity heard through the testimonies and evidence given at the Palais de Justice. A sobering and sometimes surprisingly optimistic read.

A parallel but also valuable insight into the psychology of contemporary France and the French can be found in Tom Williams’s Va-Va-Voom: The Modern History of French Football (Bloomsbury Sport, £20). Chronicling the last 40 years of the game in France with all its joys, heartbreaks, World Cup wins, disappointments and some startling scandals, Va-Va-Voom also serves as a wider social biography of France and the French over a turbulent four decades and is fascinating stuff.

The popularity of books about the landscape and natural world shows no sign of diminishing, yet makes it increasingly difficult to root through piles of po-faced exercises in overwritten self-indulgence in search of the good stuff. One writer who always delivers the good stuff is the marine biologist Dr Helen Scales, whose The Brilliant Abyss was a marvellous evocation of the deepest parts of our oceans and in this year’s What the Wild Sea Can Be (Grove, £18.99) examines the effects of human behaviour on the fauna and flora of the oceans.

Exploring the history of our seas, Scales (yes, the marine biologist has heard all the jokes) offers suggestions of how we can preserve the valuable and fragile ecosystems of our oceans while never losing a sense of awe and wonder at the deep.

Above the surface, Notes from an Island (Sort of Books, £9.99) is a beautifully produced account by Tove Jansson of the summers she and her partner, the artist Tuulikki Pietilä, spent at their cabin on the tiny island of Klovharun in the Gulf of Finland. Written in 1996 when the couple had grown too old to safely spend time there, Notes from an Island is a gorgeous evocation of idyllic times written with warmth, humanity and love. This short, beautiful book also includes Jansson’s 1961 essay The Island, one of the very first and very best pieces of modern landscape memoir writing.

Staying in the higher latitudes, a new book from Kathleen Jamie is always an event worth noting and this year’s Cairn (Sort of Books, £9.99) is another gem. Written to mark her 60th year, Jamie evokes the landscape of northern Scotland and its northern isles in a scrapbook of poems, micro-essays and thoughts that pile together to create the unified structure of the title.

Beginning with a recreation of an epiphanic moment in Orkney 30 years earlier, Jamie reflects on her own ageing and the longevity of the landscape that has inspired one of our greatest chroniclers of the land. Ruminative, immersive and utterly uplifting.

Talking of excellent landscape writing, in her early 20s, Esther Rutter arrived in Japan to begin a work placement that should have been the springboard to a successful and fulfilled life. Instead, she suffered a serious mental health episode that saw her sectioned and evacuated back to Britain ahead of a long and difficult recovery. “I had not lost just my confidence,” she wrote, “but also the belief that I would ever be happy again.”

In 2009, at the age of 23, Rutter moved to Grasmere in the Lake District as one of 10 interns spending a year living and working at Dove Cottage, the former home of William and Dorothy Wordsworth, a move that would transform her recovery and her life.

Rutter writes in All Before Me about her experiences at Grasmere through the distance of years, permitting a considered memoir of context and nuance. There is as much about the Wordsworths, the landscape and its influence on them as there is about Rutter’s journey back to herself, but such is her skill as a writer, those picking up the book for the Wordsworth connection will find themselves rooting for Rutter instead. A beautiful book.

There have been few better modern chroniclers of Europhilism than Christopher Isherwood. His fictionalised accounts of Weimar Berlin in novels like Mr Norris Changes Trains and the classic Goodbye to Berlin have become mainstays of Anglophone writing about our continent, but his years spent in Germany make up only part of an extraordinary life story. In a wonderful new biography, Inside Out (Chatto & Windus, £35), Katherine Blundell undertakes a deep exploration of Isherwood and his world.

The editor of Isherwood’s diaries and an expert on WH Auden, who exercised a huge influence over Isherwood, Blundell is the perfect teller of a wildly varying tale that as well as Berlin takes in his Hollywood screenwriting years and a period spent in a monastery under a Hindu guru. A complex story of a complex man who was a first-rate documenter of Europe at its most European.

Among other outstanding non-fiction this year, I enjoyed Jonathan Campion’s Getting Out: The Ukrainian Cricket Team’s Last Stand on the Frontiers of War (Pitch Publishing, £16.99) which movingly evokes the suffering and heroism of Ukrainians (and adoptive Ukrainians) through the unlikely prism of the nation’s cricketers.

The best music book I read this year was Will Hodgkinson’s erudite and original Street-Level Superstar (Nine Eight Books, £22), in which he spends a year shadowing the eccentric and luckless should-have-been pop star Lawrence, once of Felt, Denim and now Mozart Estate. It’s rare for a music biography to break genuinely original ground but Hodgkinson pulls it off, aided by a subject who is unquestionably unique to begin with.

Among this parade of excellent quality non-fiction however, one title stands out above the rest. On the face of it Jeff Young’s Wild Twin: Dream Maps of a Lost Soul and Drifter wouldn’t necessarily have made it to the top of my “to be read” pile. However, the fact it was published by Little Toller Books (£20), one of the best independent publishers in the country who have a rare ability to sniff out and commission incredible books, persuaded me that Wild Twin might be worth a go.

And, goodness me, it was worth a go. Not least because Young writes like a dream. The story of his teenage rejection of a life of drudgery in a Liverpool factory in favour of an “imagined Paris of water lilies, bridges, absinthe, delinquent poets and the graveyard shrines of painters and rock stars” in the early 1970s, Wild Twin could have been an over-egged slog through self-regarding indulgence. Instead it is a brilliant memoir that captures an era and time of life that coalesced into a startling European adventure the likes of which none of us could even imagine today.

The Paris plans are soon sidelined by happenstance and instead Young washes up in Amsterdam. Such is the power of his writing and the clarity of his recollection that we are immersed viscerally in a Europe on the brink of change, living all but penniless among the eccentrics, hobos, crooks, addicts, con artists and dreamers occupying a liminal part of the city, all squats and fleapits one wrong turn away from the tourist traps.

This is not the beautiful Europe of boulevards, pavement cafes and the baroque that turned many of us into Europhiles; this is its seedy underbelly, a stratum of the continent that Young makes beautiful despite the intense realism of his stories and prose.

Wild Twin: Dream Maps of a Lost Soul and Drifter is a once-in-a-lifetime read, a book that will never leave you and one that will mature with rereadings – because you will read

it again. Wild Twin is, by a distance, my New European non-fiction book of the year.