These days, Galician is the official language, alongside Spanish, of the Spanish Autonomous Region of Galicia, which is the region of north-western Spain immediately to the north of Portugal.

Historically, Portuguese was originally a dialect of Galician. It gradually spread from north to south, from the Bay of Biscay to the south coast of Iberia, as the Christian kingdoms re-took territories which had been controlled by Berber- and Arabic-speaking Islamic dynasties.

As Portugal became established as a kingdom separate from Spain, in the 12th century, however, it became increasingly common for Galician and Portuguese to be regarded as being different, even if very similar, languages. So the language which now continued its expansion westwards out into the Atlantic did so under the name of “Portuguese”.

It is not surprising that it was Portugal, the westernmost part of mainland Europe with direct access to the world via the Atlantic Ocean, which became the first major European worldwide maritime power, spreading from the Atlantic to the Indian and Pacific Oceans. During the 15th and 16th centuries, Portugal developed an enormous commercial empire, taking its language to the furthest ends of the world and leaving behind a deep legacy of cultural and linguistic influence across the globe, most notably the 190 million Portuguese speakers of Brazil.

Much of this linguistic legacy is also evident in different parts of the world in the form of mixed Portuguese-based Creole languages, such as Cape Verdean Creole and Papiamentu (TNE #331). Probably one of the least well-known of these is Macanese, which is native to Macao – about 11,000 nautical miles by the sea route from Portugal, and about as far from Galicia as it is possible to get.

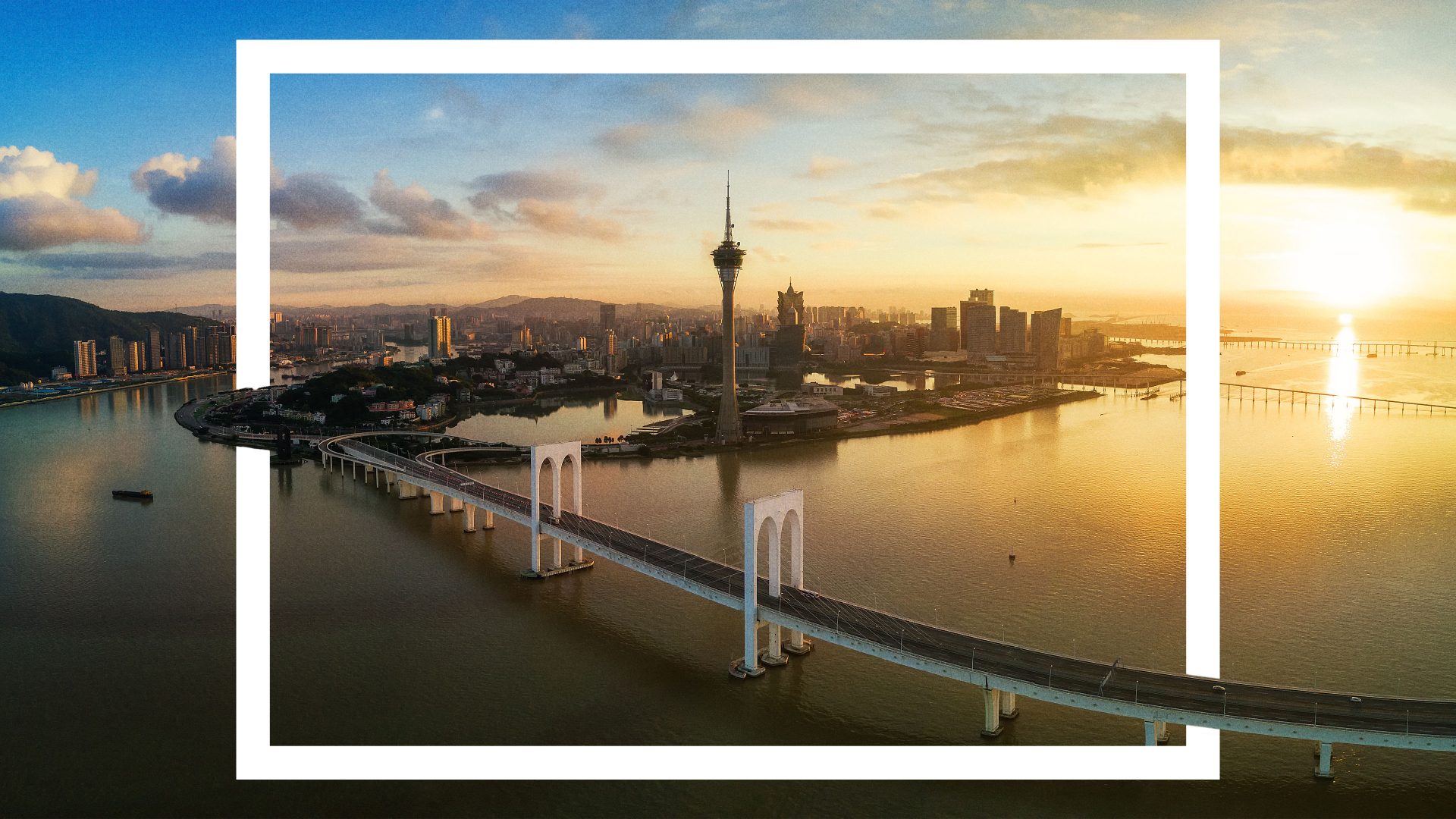

It is probably not too wide of the mark to refer to Macao as the Portuguese equivalent to Britain’s Hong Kong. Like Hong Kong, Macao is an island-based polity on the south coast of China. Macao was a Portuguese colony until it was transferred to China as a “special administrative region” in 1999. Hong Kong, also an island-based “special administrative region”, was transferred from Britain to China in 1997.

The population of Macao is around 700,000 as compared with Hong Kong’s 7 million. The native populations of both polities are predominantly Cantonese speaking. But Macao also has, or had, its own local language. Macao was very much a melting pot of Chinese, Portuguese, Sri Lankan, Indian, Malay, Japanese and British peoples and cultures, and there was a lot of intermarriage, resulting in a Eurasian Macanese population which was Roman Catholic in religion and spoke a language which was not Portuguese but was derived from it.

The language is variously called Macanese, Macanese Patois, Patuá or Papiá Cristám (di Macao) “Christian language (of Macao)”, with papia being from the same Portuguese word meaning “to chat” that we also saw in the name of the Papiamentu language of the Dutch Antilles islands (TNE #331).

Papiá Cristám retains its Portuguese linguistic base but has been heavily influenced by Chinese, with some admixture of Malay, and Sinhala (also called Singhalese, Singhala), the indigenous language of Sri Lanka.

Many Macanese people were fluent in Cantonese and Portuguese as well as Patuá, but the number of speakers of this furthest-flung offshoot of Portuguese has now sadly diminished to just a few dozen.

OCEAN

Americans often say “the ocean” to refer to what we generally call “the

sea”. This is fair enough, given that the USA has shores on both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, though it seems a little odd to us to call the Gulf of Mexico “the Ocean” and even odder to refer to the North Sea in that way.