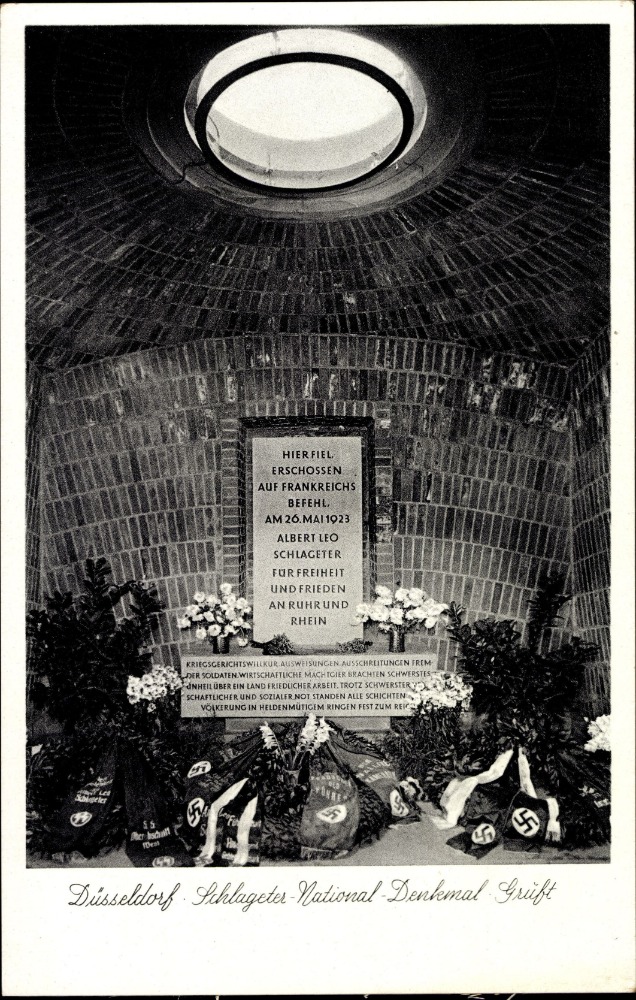

The volley of gunshots that rang out around Golzheimer Heath outside Düsseldorf on May 26 1923 marked the end of Albert Leo Schlageter’s life but also the beginning of a carefully curated legend that would help to propel Hitler’s Nazis to power over the coming years.

Schlageter, a first world war veteran and member of the Freikorps militia, was executed for acts of sabotage against French and Belgian troops, who had occupied Germany’s heavily industrialised Ruhr valley in January that year. Germany had failed again to pay reparations dictated by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended the first world war.

Until his death, Schlageter was barely a footnote to history – one of countless angry ex-soldiers searching for a cause. But, to coin a phrase, “nothing in his life became him like the leaving it.” His “martyrdom” struck a chord in a broke and broken nation where radical forces of evil were coalescing to create another global catastrophe. Schlageter’s transformation lay in the fact that, in death, he became a hero to right-wing nationalist groups, particularly the Nazis.

Born to a Catholic family of modest means in southern Germany, 20-year-old Schlageter enlisted in the army when war broke out in 1914. He fought in several major battles, including Ypres, the Somme and Passchendaele, receiving the Iron Cross award twice.

After his discharge in 1919, he went to Freiburg to study economics but dropped out after a year and joined the Baden Freikorps. He fought against the Bolsheviks in Riga during the Latvian war of independence, and took part in street battles against communists during the unsuccessful 1920 Kapp Putsch, an attempted coup against the government.

During this time, the Weimar Republic was sinking into economic disarray. It defaulted again and again on the reparations, set initially at a punishing 132bn gold marks and due mainly to France. The mark had been in decline since the war, with inflation already soaring by 1923.

After another default on a timber payment in December 1922, French prime minister Raymond Poincaré – reportedly an inflexible man with a strong anti-German bias – said he would invade the Ruhr if he did not get satisfaction. And so, on January 11, around 60,000 French and Belgian soldiers rode horses, bicycles, and tanks across the border and, without firing a single shot, occupied cities, including Essen and Koblenz. The aim: to confiscate industrial goods and occupy key coal mines, railways and factories.

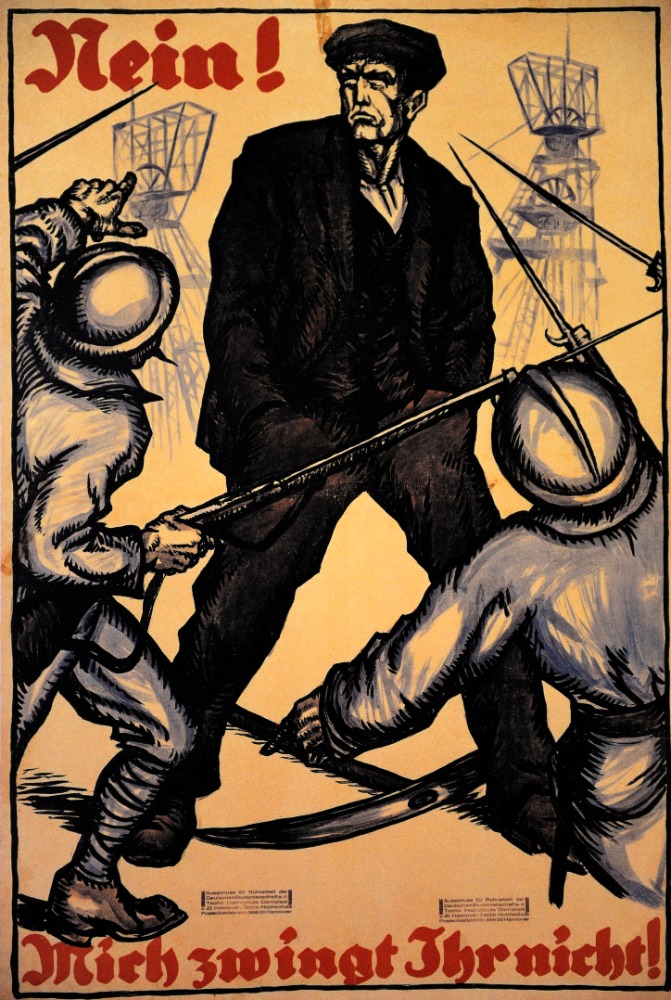

The sight of rows of soldiers on horseback trotting through the streets of Essen, and tanks lined up outside the town hall in Gelsenkirchen stuck in the craw of already humiliated German citizens, fuelling resentments that would later be exploited by Hitler and other extremists.

The government encouraged civilians to passively resist and a general strike was called. Contemporary news reports spoke of Germans gathering around statues of Bismarck and other German heroes, singing Deutschland Über Alles and shouting insults at the occupiers. Several workers were shot dead at the Krupp steel works in Essen when they clashed with French troops requisitioning trucks.

The occupying forces enforced an economic blockade that cut off the Ruhr and hammered the already weak mark – it depreciated to 160,000 to the US dollar on July 1; 242,000,000 to the dollar on October 1; and 4,200,000,000,000 to the dollar on November 20 1923.

The Ruhr occupation was not the only cause of hyperinflation but it certainly exacerbated it. Savings, pensions and wages lost value overnight, or as one contemporary journalist said: “everything was obliterated”. A loaf of bread cost 250 marks in January but 200,000 million marks by November. Money was carted around in knapsacks and wagons; postage stamps had to be constantly reprinted.

Extremists drew strength from the despair and humiliation of occupation. Hitler attempted to ride this wave by staging his Munich beer hall putsch in November but this early bid for power failed and he was sent to jail for 10 months, where he began writing Mein Kampf.

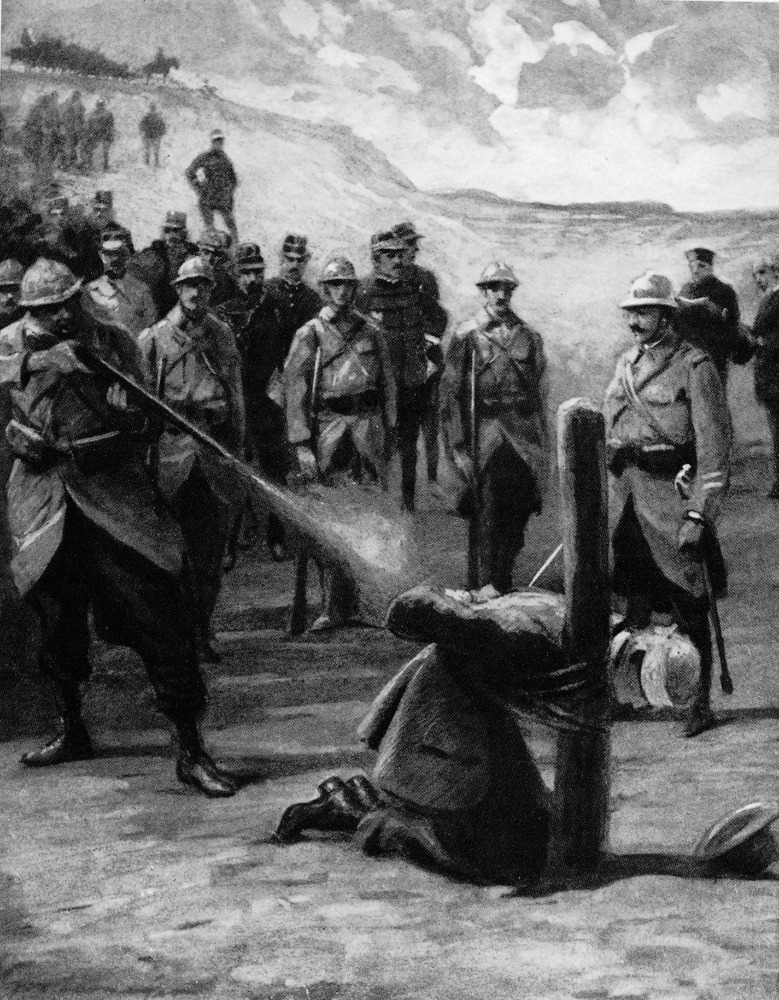

For months, the resistance continued in the Ruhr, and around 130 German civilians were killed. Schlageter, who by now had established some links with the Nazis, was there and his group succeeded in derailing several trains. But after an attack on a rail track north of Düsseldorf in March, he was betrayed and arrested. He was tried by court martial, condemned to death and executed by firing squad on the 26th.

His links to the Nazis were highlighted a few days later when Rudolph Höss, who would later become the commandant of Auschwitz and who was hanged in 1947 for war crimes, led a group of Freikorps in killing schoolteacher Walther Kadow because they believed he betrayed Schlageter. Martin Bormann, who later became Hitler’s private secretary, ordered the murder. Höss was later sentenced to 10 years in jail, while Bormann received a one-year jail term.

Meanwhile, a Schlageter Memorial Society was swiftly formed, and Hitler singled the dead man out for praise in Mein Kampf: “Schlageter has become the chief martyr of the German resistance to the French occupation of the Ruhr and also one of the great heroes of the National Socialist Movement.”

In 1931, a giant cross was erected on the heath where Schlageter was executed, and the legend was entrenched even further when Nazi playwright Hanns Johst brought Schlageter’s life to the stage in an eponymous play that he dedicated to Hitler. The chilling remark “When I hear the word culture, I reach for my revolver”, often misattributed to Heinrich Himmler and also to Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring, actually came from the play; a wartime colleague telling Schlageter, “I know that rubbish from ’18 … fraternity, equality, freedom, beauty and dignity… When I hear the word culture, I release the safety on my Browning!”

In September, newly appointed chancellor Gustav Stresemann called off the Ruhr resistance but civil unrest continued. France was also facing increasing international criticism for the occupation – Britain and the United States were always opposed – and eventually in 1924, after Poincaré had left office, France and Belgium accepted the Dawes plan to restructure Germany’s repayments and the final troops were withdrawn in August 1925.

Germany then enjoyed a period of relative economic calm until the 1929 Wall Street crash; unemployment spiralled again, wages fell and businesses floundered. Extremist forces were quick to capitalise on the Great Depression, with the Nazis becoming the biggest party.

One hundred years later as we once again witness the incongruous sight of tanks rolling through villages on the edge of Europe, Russian leader Vladimir Putin might well consider the lessons of the ill-fated occupation of the Ruhr. There were no winners, and what happened over those months led to years of unimaginable horror.