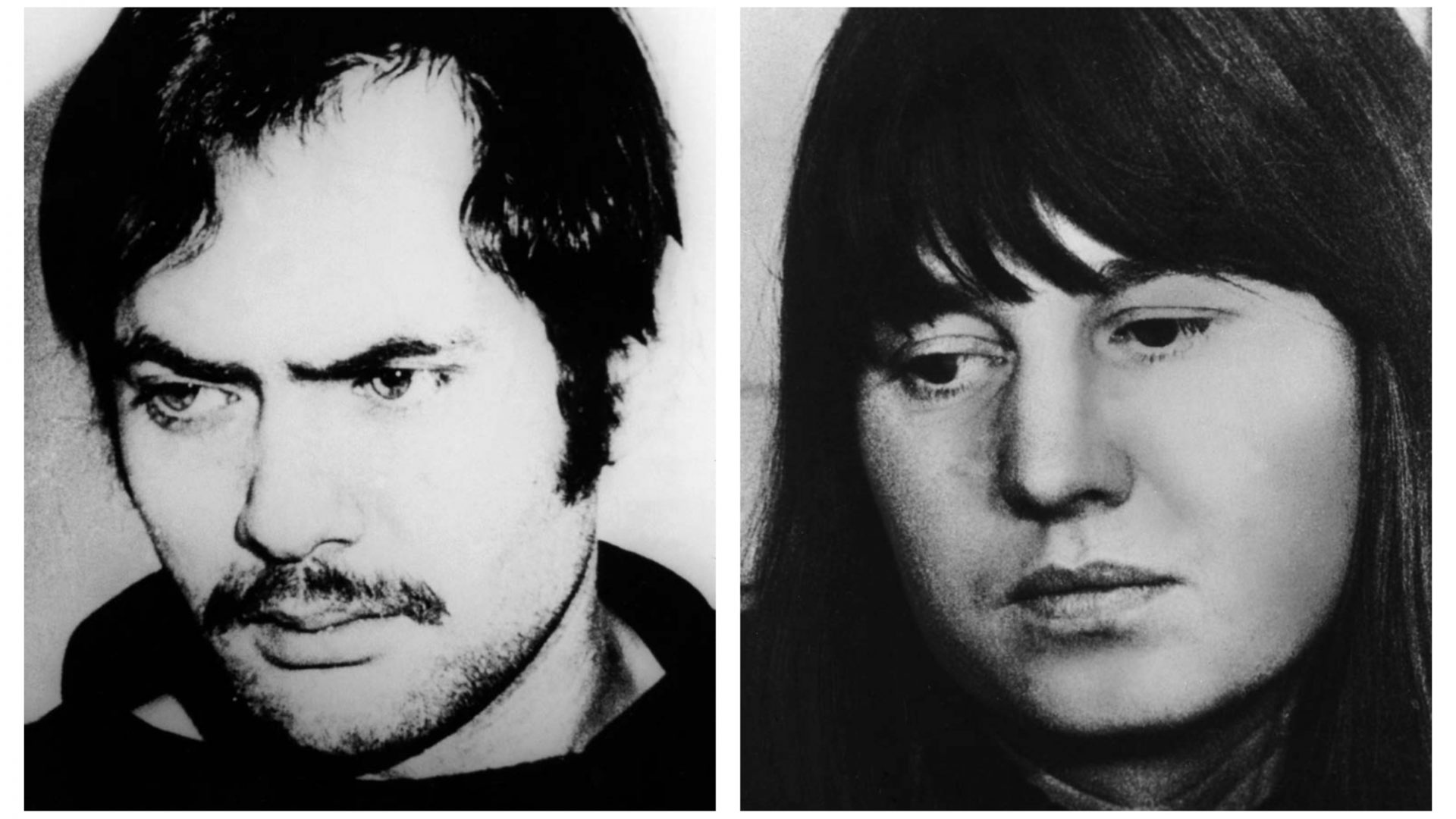

Elegantly dressed, charismatic and captivating. Andreas Baader was all of those. He was also a mass murderer.

By contrast, Ulrike Meinhof was demure, intellectual and a deep political thinker. She too was a killer.

“I guess it was a form of misplaced glamour, our Bonnie and Clyde,” says Sophia Fischer, a student of politics at Heidelberg University in the early 1970s. “I knew the killing was wrong. But we agreed with their aims.

“We knew what happened to our parents’ generation before the second world war, so we embraced anything radically opposed to the old politics. Like the IRA. Irish republicans could agree with the aims, but not the means.”

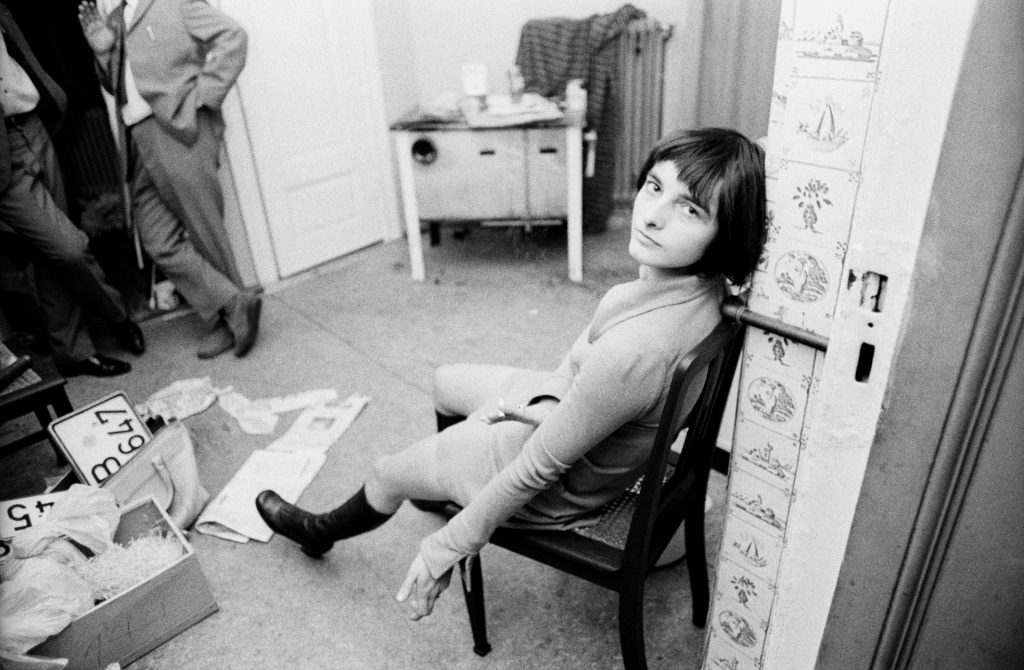

Fischer is talking about what became known to the English-speaking world as the Baader-Meinhof gang, a terrorist cell that operated in West Germany and beyond. The name resurfaced recently, when Daniela Klette, the last member of the network still on the run, was captured after 30 years of evading the authorities. “Baader-Meinhof terrorist had weapons stash and gold bars hidden in wardrobe” was the Telegraph’s headline.

Yet Baader-Meinhof was a name the group itself never used, insisting that, in accordance with Marxist-Leninist dogma, it had no leaders. It designated itself the Rote Armee Fraktion (RAF), (Red Army Faction in English). Whatever the title, from 1967 onwards it would assassinate more than 30 people and injure at least 200 others, alongside a campaign of bombing, kidnapping and robbery that terrorised a nation. But equally, and controversially, they became a source of mesmerising fascination for public and press alike.

“Yes, they committed atrocities. And I knew that was wrong,” admits Fischer. “But there was that edgy allure. My opinion today has totally changed, their acts were unspeakable, despicable. Looking back, though, I wonder how many students in my class were beguiled. And whether any had closer ties with them than they should have.”

The RAF returned to the headlines – not that it ever truly left them, in Germany at least – on February 26 when Klette was arrested in Berlin. She had been part of what was known as the third-generation RAF, which emerged after two earlier cohorts died or were imprisoned.

Klette had been in hiding since the 1990s, wanted for armed robbery and attempted murder. She stands trial later this year.

So why does the organisation that held West Germany in fearful thrall for years still hold such sway over the public consciousness today, in a way that perhaps no other violent political movement has done before or since? There’s what Fischer termed the “misplaced glamour”, but also there was the ideology. Meinhof’s manifesto for the RAF, written in 1970 and entitled The Concept of the Urban Guerrilla, demanded a left wing revolution to overthrow the capitalist West German state and the ex-Nazis who they believed still controlled it. Its cover was adorned with a red star alongside a Heckler and Koch machine gun – an image commissioned by Baader.

The manifesto struck a chord with sections of the nation’s youth, especially students, driven by a belief that West Germany’s postwar ruling class was merely a continuation of the Third Reich. Former Nazis such as Kurt Georg Kiesinger, who became chancellor in 1966, were at odds with Germany’s postwar youth, driven by its implacable opposition to capitalism, imperialism, racism, the US military presence in West Germany and more.

Germans have a word for postwar collective guilt: Kollektivschuld. For young people especially, this loomed large.

They believed they lived in a state of bourgeois conspiracy supported by a compliant media, with newspaper mogul Axel Springer, publisher of the conservative daily Bild, a particular nemesis. That Meinhof’s words stipulated the necessity of violence did not deflect from the political concept, which appealed to those born in the immediate aftermath of Nazi Germany.

They were not alone. The radical student movement had taken hold in industrialised democracies around the world throughout the 1960s. Rioting, striking and street protests were commonplace.

The list of grievances was long, the flashpoints diverse. Anti-Vietnam war sentiment ran high, as did support for the US civil rights movement. Protest reached its peak in the summer of 1968 with riots in cities as disparate as Chicago, West Berlin, Mexico City and, most notably, Paris.

It was in this febrile environment that the ideology of the RAF thrived. Emboldened by the success of the Cuban revolution at the start of the decade, and struggles as varied as the anti-imperialist uprising in Portuguese-administered Mozambique or the actions of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, they set out to supplant the old guard.

Alongside the eponymous Baader and Meinhof were other early adopters of its dogma. Holger Meins, Gudrun Ensslin and Jan-Carl Raspe had long been under the gaze of the authorities as they progressed from early 1960s student radicalism to arson and rioting.

Ensslin and Baader had already been convicted of burning stores in Frankfurt in 1968 as they protested against the Vietnam war. But the RAF first came to public attention in 1971, when police sergeant Norbert Schmid was shot dead while arresting RAF member Margrit Schiller in Hamburg.

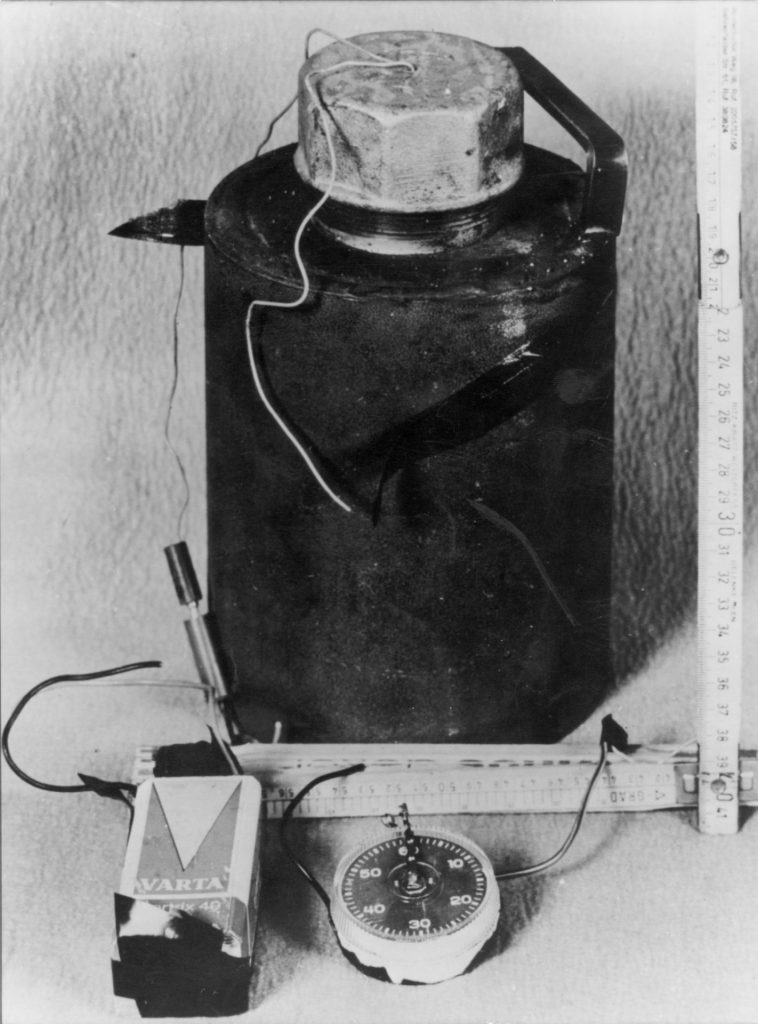

And then the whole world was put on notice when the US Army’s V Corps Frankfurt headquarters was bombed in May 1972 in protest at “United States imperialism and occupation”. Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Bloomquist died as the Rote Armee exploded on to TV screens around the globe.

No matter that the postwar “economic miracle” had, in only 25 years, transformed a shattered nation, any link to Nazism or the state was deemed fair game. “Dare to struggle; dare to win!” wrote Meinhof, adding without irony: “We are acting for those trying to free themselves from terror and violence.”

Ensslin also laid bare her own contradictions when she stated: “Violence is the only way to answer violence.”

“It was a disturbing time,” remembers Inga Meyer, 64, from Dusseldorf. “My school was near the police station. Often my mother didn’t want me to go, fearing an attack. When you’re 13, that spooks you. I’ve never forgotten it.” Roadblocks, armed police on the street and raids on student homes became part of everyday life.

But the authorities were closing in. Baader, Meinhof, Raspe, Ensslin and Meins were arrested in June 1972. Their trial would take five years.

Meinhof would not see its conclusion. She ensured notoriety by hanging herself in 1976, while Meins had died on hunger strike two years earlier. Conspiracy theories abounded, but widely accepted today is the belief that Meinhof was being bullied by Baader and Ensslin and, in deep depression, had killed herself.

“People were genuinely angry,” says Armin Becker, 72, then a student at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. “While older people were saying good riddance, some people my age thought she had been murdered by the state. And even if she hadn’t, the state drove her to suicide.”

Fischer adds: “I recall fellow students posting Meinhof’s photograph on campus with messages saying the struggle would go on.” And it did. The second generation RAF, which emerged following incarceration of the original members, was seemingly deadlier than the first.

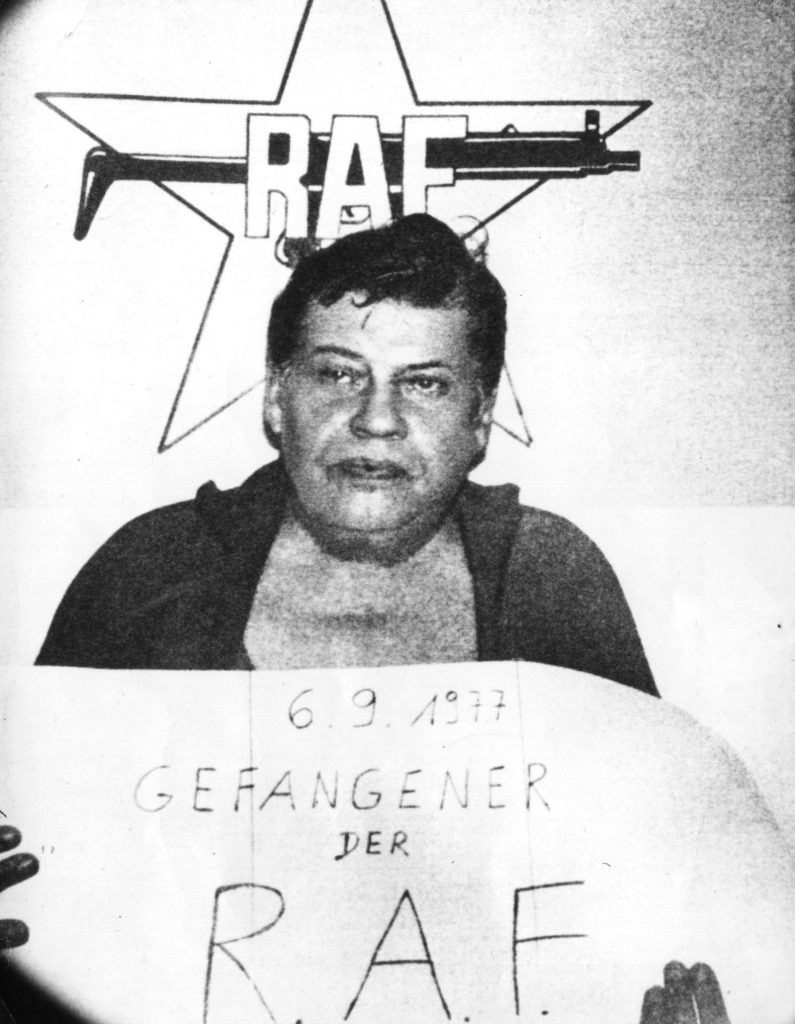

In what became known as the German Autumn of 1977, Jürgen Ponto, CEO of Dresdner Bank, was shot dead, the attorney general and ex-Nazi Siegfried Buback was killed alongside his bodyguard, while numerous police officers including Dutch border guards were killed in shoot-outs. Finally, in an attempt to secure the release of jailed gang members, Hanns Martin Schleyer of the German Employers’ Association was kidnapped.

The nation was in turmoil. But nobody, least of all the government, was prepared for what followed.

On October 13, members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine hijacked Lufthansa Flight 181, making similar demands to Schleyer’s abductors. After the plane landed in Somalia, West German forces stormed it, freeing the passengers and killing the hijackers.

But while chancellor Helmut Schmidt was congratulating his government and the rescuers came the bombshell denouement. Determined to hog the headlines to the end, Baader, Ensslin and Raspe killed themselves in their cells. Martyrdom and notoriety once more hand in hand. And it got worse for Schmidt: Schleyer’s captors murdered him.

But although the killing rolled on, with Nato supreme commander and future US secretary of state Alexander Haig only narrowly escaping death in a landmine attack in Belgium, the RAF had miscalculated. The public mood shifted that autumn of 1977.

“The killing of Schleyer changed things,” says Volker Sommer, 74, from Bielefeld, a student when the RAF was active. “Any support or secret sympathy for the group stopped right there.”

“It’s true,” says Fischer. “Schleyer was seen as a totally innocent party. I remember my dad calling and asking if this is what I believed in. And I said no. I said no immediately.” If ‘terrorist chic’ was ever an extant trend, maybe it died alongside Schleyer.

Klette’s third-generation RAF remained officially active until 1998, when it declared in a letter to Reuters that its activities had ceased. The group had claimed 34 victims, while 27 of its members also died, killed by security forces or by their own hand.

So, 54 years after its formation, how are the activities of the RAF viewed today? “They enjoyed the violence, the killing,” says ex-policeman Stefan Kurz, 76, from Kaiserslautern. Kurz investigated the murder of police officer Herbert Schoner, shot in an RAF bank raid in 1971. “My life was at risk every time I walked the streets. We weren’t puppets of the state, we were protecting innocent civilians. RAF can wrap their murders in a veil of ideology, but they were murders, pure and simple.”

Jakob Neumann, 79, was involved in local politics in Hamburg in the 1970s. “I was a supporter of the radical left,” he explains. “But I spoke out against RAF violence, and the bombing of Axel Springer’s Hamburg offices. We have a ballot box for changing political direction, not guns. But even though politically we agreed, I became a target. I needed police protection after death threats arrived at my home. They were on the wrong side of history.”

Celia Werner, 77, then a book translator from Bonn, has a different take. “Until Schleyer, people – certainly students and those on the left – were prepared to turn a blind eye,” she says. “Their targets weren’t indiscriminate. And although perhaps the violence was condemned, their political aims weren’t. They were a military wing of the new politics.”

Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre was one of many intellectuals prepared to defend the group publicly, and former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer was a one-time sympathiser.

The individuals themselves, especially the first-generation RAF, also commanded grotesque interest. Ensslin was Baader’s girlfriend, of striking appearance – an asset perennially popular with the tabloid press – and, alongside Meinhof, the brains behind the movement.

Raspe was considered the group’s conscience, only advocating violence when “absolutely necessary”. Hunger striker Meins won sympathy for being prepared to die for his beliefs.

And then there was Petra Schelm, killed in a police shoot-out in 1971. A hero to the radical left, she was revered in much the same way as executed Argentinian revolutionary Ernest “Che” Guevara was by the insurgencies of south and central America. All were consummate manipulators of the media narrative, up to and including the suicides.

But antisemitism was rife too –founder member Horst Mahler is now a Holocaust denier – as were links to the notorious East German security service, the Stasi, who helped to train, arm and fund group members. Indeed, many fled to communist East Germany to avoid arrest.

But what of the eponymous founders? It was said of Baader that had he not been involved in ideological terrorism he would have been a gangster. Handsome, but naturally violent, including to his girlfriend Ensslin, he lived the mobster lifestyle: guns, fast cars, sharp suits.

Meinhof, meanwhile, was a former prison counsellor of once-pacifist outlook. It seems she was thrust into the RAF when, working as a journalist in 1970, she witnessed a librarian being shot as Baader escaped from prison.

She had no need to, but instinctively fled with, and then joined, the gang. The allusions to Bonnie and Clyde might be extraneous – the American bank robbers were quite happy to indulge in capitalism of a form – but both pairs were beneficiaries of popular myth and injudicious reverence.

Yet still the arguments rage. When Der Baader Meinhof Komplex, a 2008 film depicting the group’s reign, was released, it was accused of glorification. Good-looking actors seemingly portrayed fashionable intellectuals. Others defended the movie arguing that, rightly or wrongly, it’s how people perceived them.

The RAF emerged at a confluent point in its nation’s political history, an egregious juxtaposition of social division, cultural discord and, quite simply, unpropitious timing. Yet in the final reckoning the RAF’s ends could never justify the means.

Most Germans have come to terms with their country’s postwar legacy in a way the RAF could not. The word Vergangenheitsbewältigung means “coping with the past” through confronting the nation’s history. Germany is now at the forefront of the progressive values espoused by the European Union.

So terrorist chic surely has gone the way of the RAF itself. Well, Google Baader-Meinhof T-shirts and decide for yourself. The faces of Europe’s most notorious urban guerrillas will stare right back at you, machine-gun logo to the fore. You can even buy a shirt with the words “Prada-Meinhof” adorning it.

The irony of capitalism profiting from violent left wing agitation presumably passed the makers by. But it might explain why, even today, there are some demanding that Daniela Klette be treated with leniency.

Some interviewees’ names have been changed