Claude Monet might have been thinking of his native France, or of Italy, so influential to generations of artists, when he wrote in 1901 to his wife, Alice: “There is no country more extraordinary for a painter.” But it was England he had in mind, and, in particular, London. Then the most populous city on the planet, its size, bustle and relentless innovation simply dazzled him, as it did the rest of the world.

The artist had been visiting the capital since 1870, and had visited his son, Michel, who was studying English in London, when he was ill, in 1888. But it was in 1899 and for the following two winters, by now highly successful and wealthy, that he booked into the recently opened luxurious Savoy hotel and set about painting over and over again three views from his high balcony: downriver to the old Waterloo Bridge, upriver to Charing Cross bridge, and over the river from its south bank to the Palace of Westminster.

Some 100 canvases were shipped back to France, where he would continue working on them for years. “Most people think I paint fast,” he told a journalist in 1901. “I paint very slowly. I am never contented with my work. I let a picture go because I would work on it for ever if I did not.”

The result of endless scrapings and repaintings was a landmark exhibition at the gallery of his Parisian dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, in 1904, in the 9th arrondissement, on the Rue Lafitte – the same street on which the artist was born in 1840. There was huge interest in the three-roomed show, but some critics were hard to please.

The high-minded Burlington magazine believed the paintings lacked “the peculiar atmosphere of foggy London”, adding that “the almost morbid charm of the light in London is perhaps impossible to catch”. This judgment, had Monet read it, would have really stung, for catching the light, the fog, the peculiarity, was exactly what he had set out to do. Durand-Ruel himself cornered several of the 24 pictures that sold, and 13 were returned to the artist.

Monet was determined to mount another show, this time in London itself, with newly worked-up pieces. He approached a gallery, considering its three rooms to be ideal for his three subjects, and pencilled in the private view for March 30, 1905.

As in Paris there were to be 37 works, of which 21 had still to be finished. And then, on March 7, a notice appeared in the press to say that the exhibition was postponed. More than postponed; it never took place.

It would not be until 1908 that the city saw work from the series that Monet called his “Londres”, when one – and only one – was included among 900 paintings in a Franco-British exhibition at White City.

Today these atmospheric and elusive Thames scenes are highly prized by galleries and private collectors worldwide, but the reluctance of early 1900s Britain to see London through Monet’s eyes is partly understandable. Efforts were beginning to clean up the dangerously filthy air. The Dickensian-sounding Fog and Smoke Committee, founded in 1880, became the National Smoke Abatement Society, which appointed inspectors to measure pollutants, including soot and sulphur dioxide.

In that decade, an estimated 700 deaths a week nationally were attributed to bronchitis, exacerbated or caused by fog. With innovations for reducing smoke from domestic fires on the market and pressure from scientific journals, in 1896 the Public Health (London) Act was passed, the start of measures to protect public health through regulating air quality.

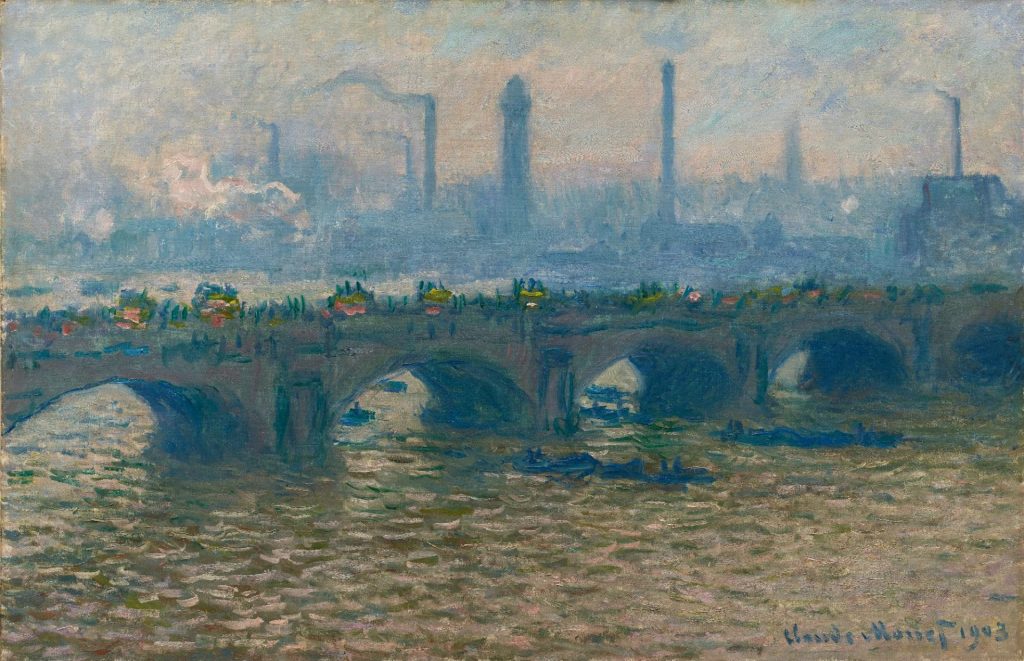

This, then, was the London that Monet so admired. Coal fires blazed, roads were choked and heavy industry operated on the south bank, within a few metres of the nation’s decision-makers in their extravagant Gothic revival sanctum.

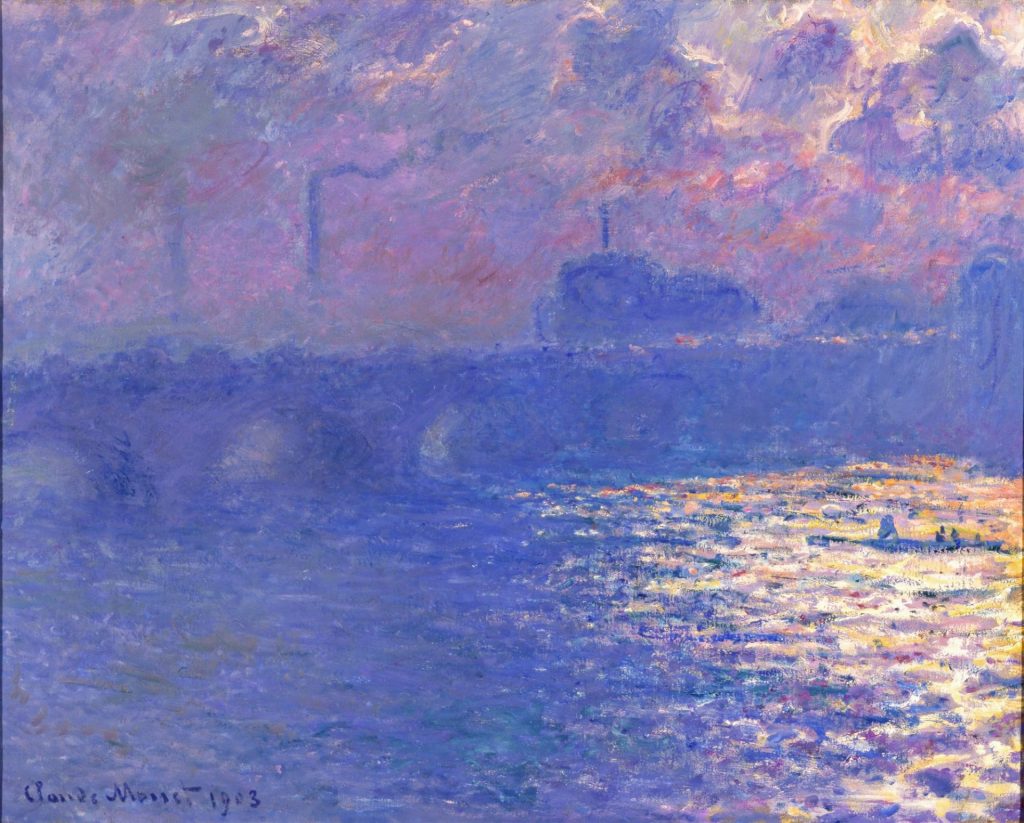

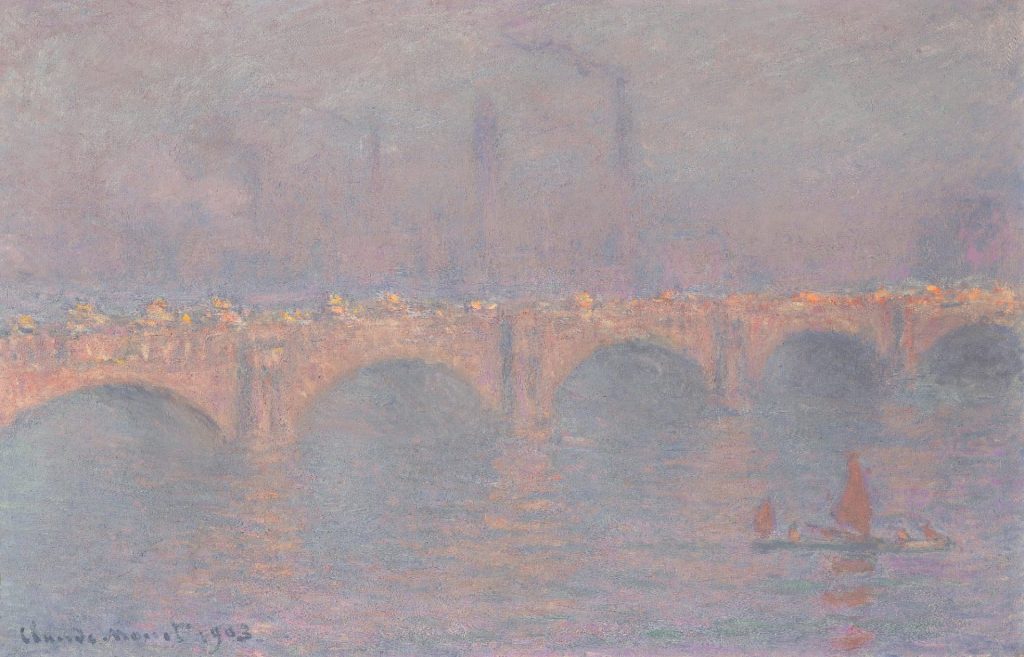

Monet was entranced by the colours created in the filthy London air, rhapsodising about them in letters and working across a wide range of pigments in views that sing out in pinks and oranges, glow with thick, golden cream, and alarm with expanses of livid green and blanketing grey.

Images: The Courtauld

As far as industrial emissions go, Monet had form. In 1877 he had created 12 paintings of the Gare Saint Lazare in Paris, revelling in the billowing pillows of steam as he looked down from above.

Looking down was an important aspect of his three London Thames painting campaigns too. For the first two years his rooms at the Savoy were on the sixth floor; in 1901 he was relegated to the fifth, the sixth having been commandeered by Princess Louise for officers wounded in the Boer war. In this year, Monet would get a bird’s-eye view of Queen Victoria’s funeral procession, thanks to his burgeoning friendship with the well-connected painter John Singer Sargent.

Sargent would introduce Monet to the wealthy society hostess and patron of the arts Mary Hunter, and she would play an influential role in the Palace of Westminster paintings. Through her friendship with a leading physician at St Thomas’ hospital, across the river from the Houses of Parliament, Monet was able to set up a second painting station, this time in hospital offices, again above river level, and at the eastern end, so that wide expanses of the river were included in his view across the Thames.

For his Westminster pictures, he ordered specially made square-ish canvases instead of the off-the-shelf rectangular supports, as favoured by painters of seascapes, that he used for the bridge pictures. Once returned to France and worrying away at his Westminster pictures he would ask Hunter to send him photographs of the scene, as an aide-memoire, requesting that both be at high tide, one when the water was calm, one when it was agitated.

When word got round that he had fallen back on photography, he was indignant. “Whether my cathedrals, my Londons or other canvases are done from life or not is no one’s business and is of no importance,” he wrote to Durand-Ruel, who was nervous about the gossip. “I know so many painters who paint from life and only make horrible things…” But Durand-Ruel warned, “It would be unfortunate were such a rumour to circulate around London… It would be bad for the success of the exhibition that you are preparing…”

An exhibition of London pictures, never to materialise in Monet’s lifetime, is finally, some 120 years later, taking place, curated by Karen Serres. For the first time in their colourful lives, 21 of his “Londres” have been reunited, thanks to generous loans to the Courtauld Gallery from important institutions and private owners from many countries.

Seeing the Charing Cross Bridge, Waterloo Bridge and Parliament pictures lined up together, in close proximity and on walls painted to suggest the “pea-souper” fogs of those times, is a giddying experience. And prized as each one of these works is individually, it gives a real insight into why Monet regarded the series as a single entity, and why he worked tirelessly on each one, constantly changing the dialogue between contrasting works on the same subject.

Of the 21 works, 18 were shown in the Paris 1904 show – half of its pictures. “New” works include the only two Monet London pictures in British collections, both looking west towards the Houses of Parliament, entitled simply Charing Cross Bridge (1902) (although Monet was fairly free and easy with his dating), and with remarkable stories of their own.

With its strong horizontal bridge line, sliver of embankment, and ghostly vessels, one was in the artist’s possession until 1910, when it was donated to a raffle raising funds for victims of the Great Flood in Paris that year. The lucky winner sold it on – to Durand-Ruel.

He in turn sold it to the 9th Duke of Marlborough, who sold it on yet again, this time to the visionary Welsh collector Margaret Davies, who, with her sister Gwendoline, on inheriting a great fortune from mining and railway building, amassed an innovative 20th-century art collection. They left 260 works to the National Museum Cardiff, among them, Charing Cross Bridge (1902).

In the other British-owned Charing Cross Bridge (1902), the puff of steam as the train crosses the bridge is central to the picture, and the Houses of Parliament are hard to make out. Having passed through several hands, the picture was given to Winston Churchill in 1949, as a joint 75th birthday and Christmas present by his literary agent and admirer Emery Reves.

That parliament was shrouded in fog alluded to Churchill’s own ousting from office four years earlier and Reves’s hope that the leader of the Conservative opposition would be returned to power – as he was, in 1951.

Monet, having given up on the London exhibition, turned his attention to his garden in Giverny, Normandy, and to the waterlilies series which would ultimately dwarf the Londons in scale and number and occupy him until his death in 1926. Nearly a century later, the Courtauld’s incomparable exhibition goes a long way to fulfilling the dream he abandoned.

Monet and London: View of the Thames is at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until January 19