I recently drove from Rome all the way to Sicily for a beach break, and the journey gave me time to contemplate Italy’s dysfunctional infrastructure.

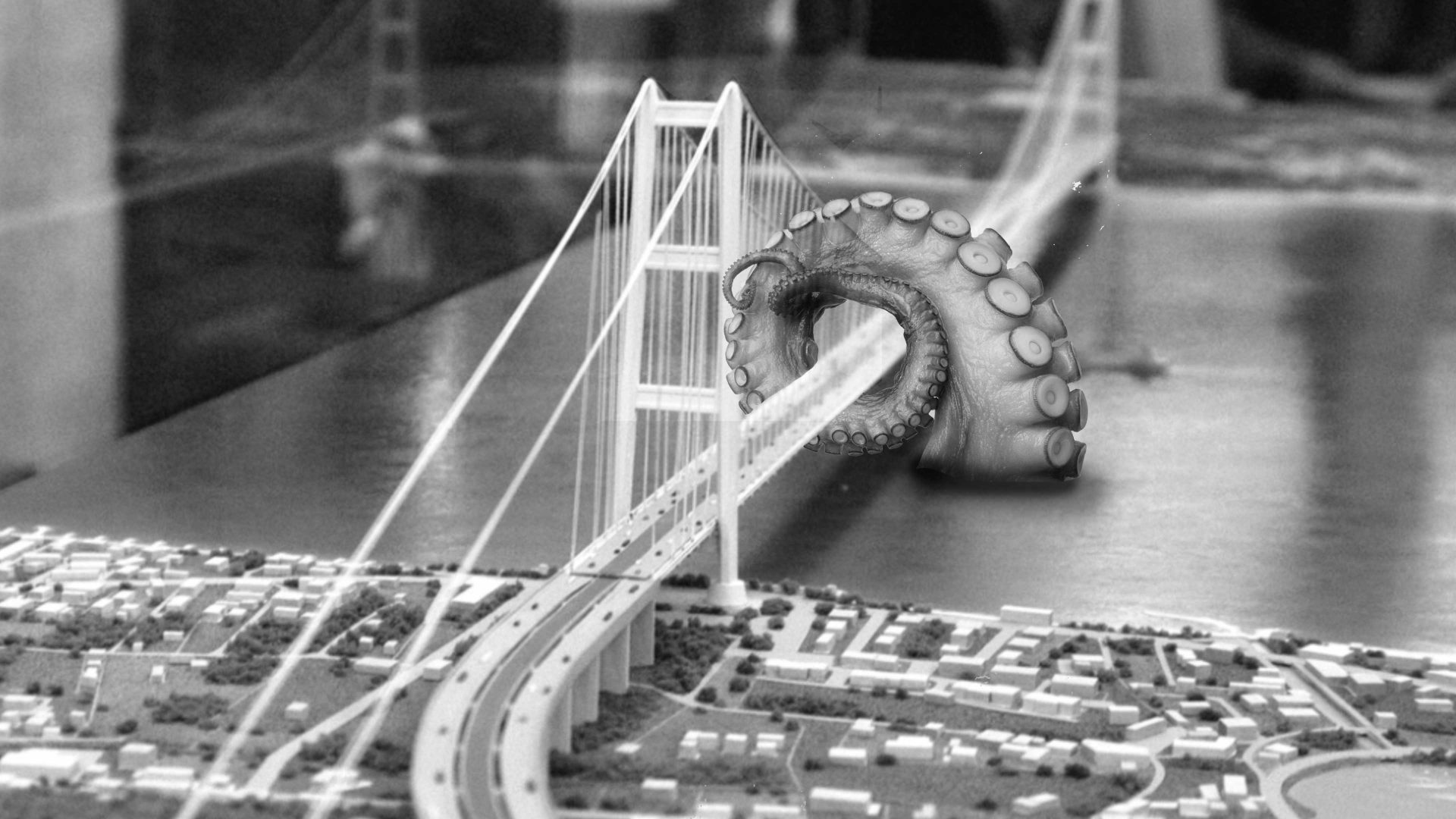

The rightist government is reviving plans to build a bridge connecting Sicily to the mainland. Their name for it is “the Straits Bridge”, as it links the Sicilian city of Messina to the Calabrian, southernmost town of Villa San Giovanni, where cars and trucks currently take a ferry across the choppy waters.

In ancient times, it was believed those straits were inhabited by two ugly sea monsters that whipped up currents and strong winds in order to wreck ships. Now, politicians are planning a futuristic bridge to span the treacherous strip of sea.

But many Italians don’t buy it. The problem is not the bridge – if and when it is ever built. The problem is that the roads are terrible – not only the ones that link Sicily to the Italian mainland, but also the ones connecting the isolated Sicilian interior with the island’s largest cities.

My road trip into the deep south was hell. It was nine hours long. Luckily I had company. The main highway running along Italy’s backbone all the way to Calabria is nicknamed the Autostrada del Sole, (the Sun Motorway) and it has recently been finished after decades of delay. Well – almost finished. It is the only piece of high-speed infrastructure connecting the north to the south.

The scorching sun was almost melting my car tyres as I stopped for an espresso. Some parts of the motorway are still works in progress, or are being given yet another makeover to patch up holes and cracks.

As I drove on patiently, I thought about a movie called Benvenuti al Sud (Welcome to the South), where drivers, stuck in kilometre-long traffic jams, would stop their cars and organise impromptu street picnics, with music and dancing. During eight hours of waiting, they’d move their car just a few inches further down towards Sicily.

At Villa San Giovanni, waiting to take the ferry across the Messina Strait, I talked to a few angry Sicilians who were going home. Giuseppe, a graphic designer, told me that his life as a commuter was a nightmare. Once a week he travels from Caltagirone, a small Sicilian town, to Como in Lombardy. “I wake up at three in the morning, drive my car for four hours to Catania airport to jump on a plane to Milan, take a car to Lake Como, and in the evening back home. It’s impossible to find a fast bus or train within Sicily to get to the airport. I’ll be an old man before I ever catch one.”

Giuseppe doesn’t believe the Messina bridge will make things better – if anything, it will make them worse. Everyone will hop in their cars, excited to drive along the sleek new bridge, and the result will be huge traffic jams.

“This country needs more roads, more trains, more green infrastructure. Not a stupid bridge.”

“Italian politicians seem to love odysseys, mythology, and dreams of grandeur. Their idealism is more than just the opposite of realism. It’s a utopia, and the Messina bridge is the epitome,” says Giovanni.

I couldn’t agree more. Last year it took me five hours just to drive a few kilometres across Sicily. I got lost on winding, dusty country roads because the main routes were shut. At one point, when it was already dark, I found myself surrounded by sheep, on the edge of a precipice.