On the south-east outskirts of Paris, among the trees of the Bois de Vincennes, a former royal hunting ground, stands La Cartoucherie. It was once a munitions factory built to replace an earlier, exploded gunpowder store, and it still delivers regular explosions.

Since 1970 it has been the home of Théâtre du Soleil, a company then just

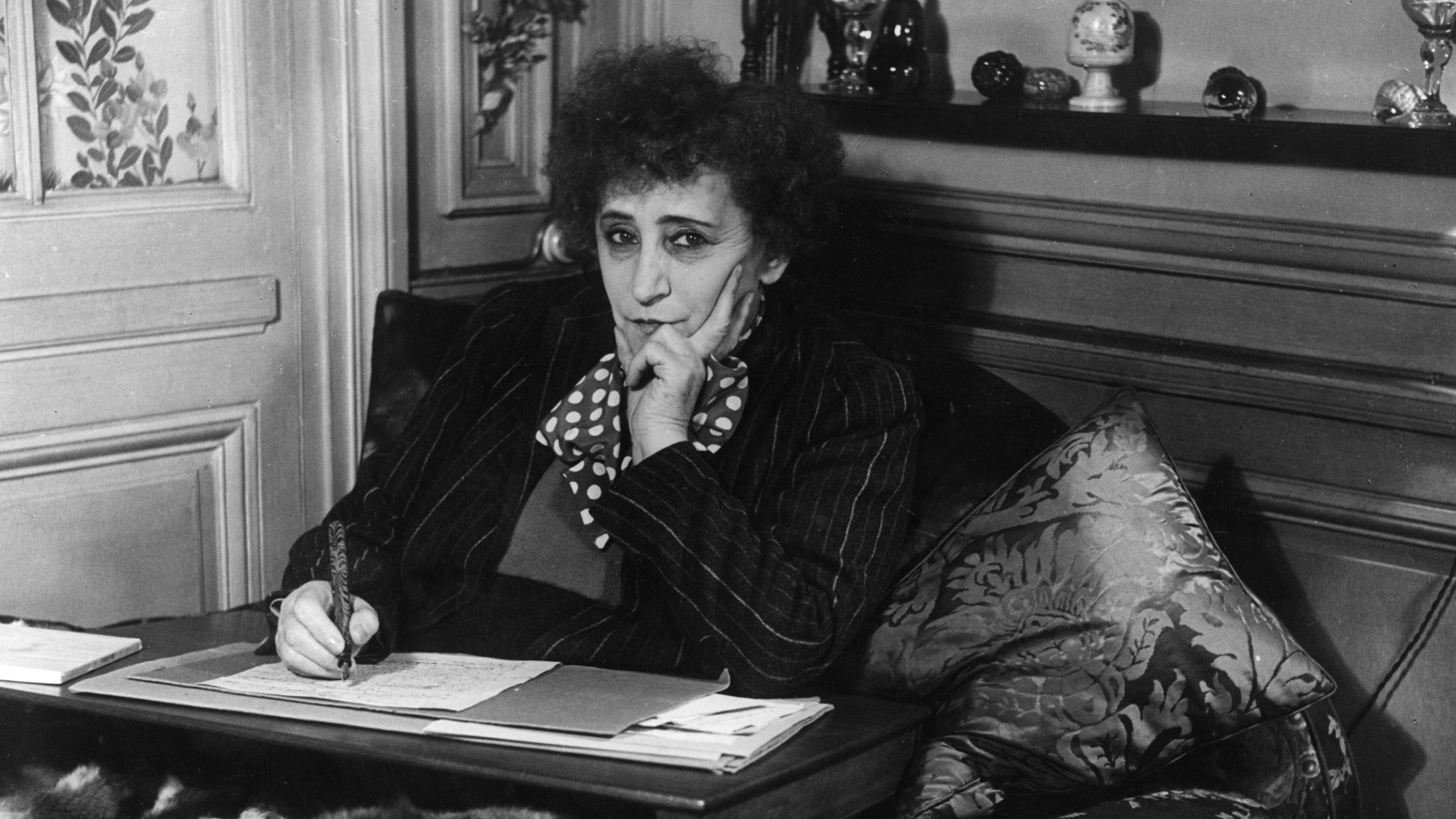

six years old. Today it is still under the directorship of one of its original

founders, 83-year-old Ariane Mnouchkine. Théâtre du Soleil first rehearsed within the Cartoucherie’s ruined walls, later rebuilding the site into its present-day configuration.

It is a story that cements the myth and makes true the director’s belief in the transformative power of theatre. “It offers up enough empty space to create what you want from it,” actress and company member Astrid Grant tells me. “And we’re not afraid to break down a wall if we need to…”

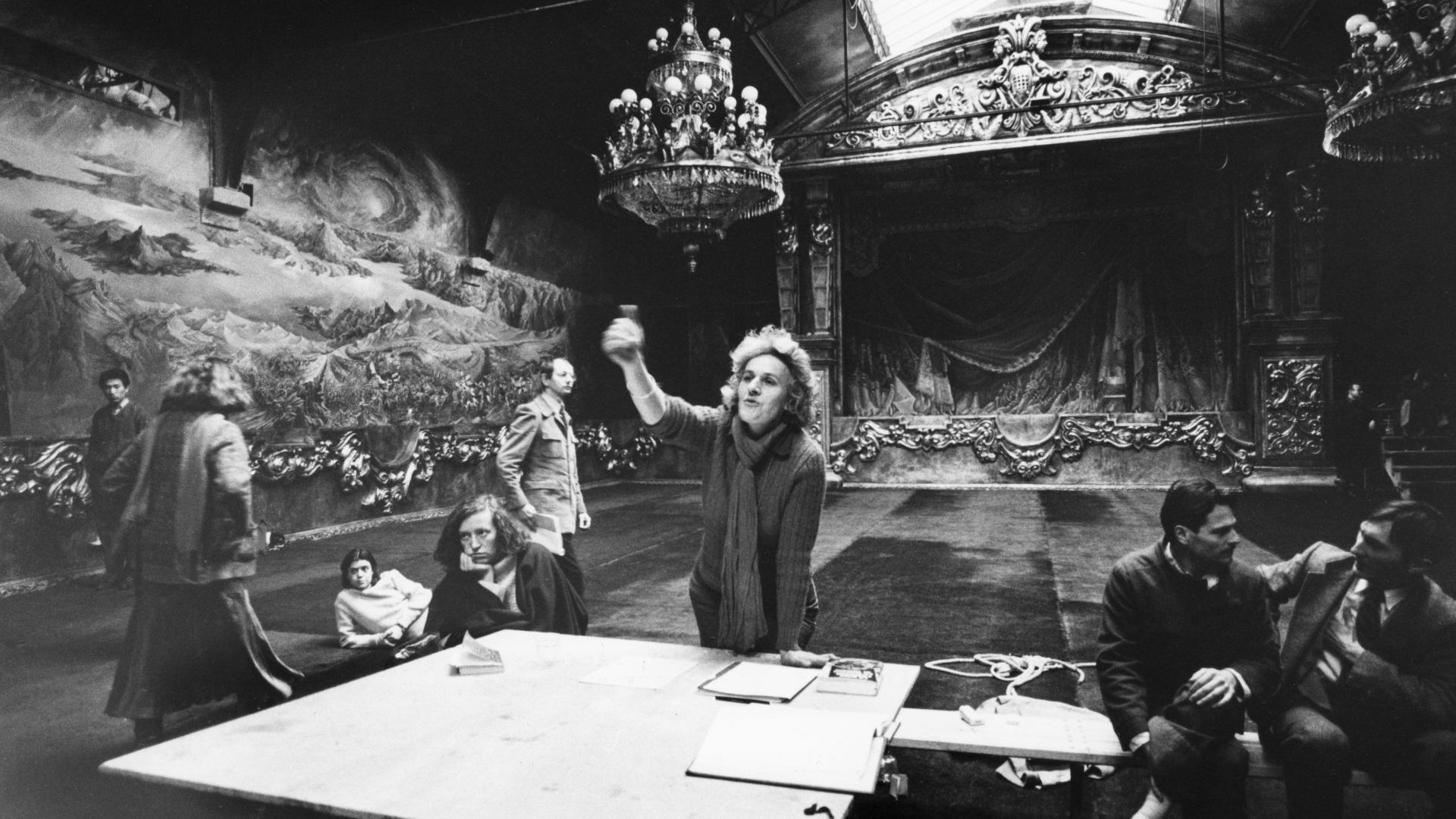

Ambitious productions, often international in character and epic in scale, with a multinational team of 80 to 90 that includes performers, tech, costumes, props and admin staff, and a rehearsal period that can extend well beyond a year, is unusual, even for a company of such longstanding. Théâtre du Soleil has evolved over its 58-year history, from an unfunded collective of 20 to an established Grande Dame, generously supported by France’s culture ministry, with a loyal following that ensures when a show does come around, its 500+ seats are full.

Mnouchkine directs every play, favouring a collaborative, co-creative approach with improvisation and group work where “everything from everyone is part of the production”. Performer Judit Jancsò says: “The things that we do together are more than the sum of us individually. We work with people we like working with so it’s family. It sounds utopian and we don’t always get along, but we have learned to work for a cause, for a play, for a show. It’s good to come to this place and be someone else for a time”. Hierarchy is more or less dispensed with. Someone in the office may end up on the stage, and vice versa. Everyone is paid the same.

In Théâtre du Soleil’s repertoire, you’ll find classics from Shakespeare, Molière, Euripides and Aeschylus, intermixed with original creations: 1789, Et Soudain des Nuits d’Éveil, Le Dernier Caravansérail.

Some draw inspiration from the world’s oldest theatrical forms, notably those from India and Japan. Its current show, L’Île d’Or (Golden Isle), is one such. Mnouchkine first visited Japan when she was 23, taking a boat to Yokohama, where she was smitten by the Shinto rituals in everyday life. Theatre was her great adventure and, along with two long-term collaborators, the writer Hélène Cixous and the musician-composer Jean-Jacques Lemêtre, she has worked with Noh and Kyōgen masters to create

Gesamtkunstwerk, “total theatre”. She is also a recent recipient of the Kyoto

prize (2019), which has part-funded L’Île d’Or.

For this play, La Cartoucherie is transformed into Mnouchkine’s Palais des Merveilles (Palace of Wonders). You start by walking through the wooded

entrance, passing the school and riding stables and one of four additional theatre companies that share the complex, to reach the modest stone exterior of the auditorium. The wintry leafless trees and the chilly air of isolation give way to the warm hubbub of the crowd in a huge foyer, eating rice and ramen at trestle tables adorned with chopsticks and soya sauce; above them sway rows of lighted lanterns, the walls dance with large Hokusai-style ink drawings and people cruise the bookshop and the bar. “Everything is about gathering and celebrating humanity,” says Grant.

This spirit of generosity continues inside the theatre. From the front of the stage, Mnouchkine apologises: “The heating is on low,” as folded blankets are ceremoniously delivered to the audience, “out of respect for the planet, for Ukraine and for the resources of Théâtre du Soleil.”

L’Île d’Or is a three-and-a-half-hour colossus of vignettes stitched together by the conceit of a hospitalised Mnouchkine-double, Cornélia, who dreams she’s at a theatre festival on an island in Japan. This dream of Kanemu-jima, (L’Île d’Or) also has its real-life counterpart in the Japanese island of Sado, historically home to goldmines and exiles, which the company was due to visit in 2020 until the pandemic curtailed the trip.

Thus begins a journey that takes in multiple characters at every level of society from fishermen, a washerwoman, students, a lawyer, policemen, a merchant, puppeteers and theatre troupes from Hong Kong, Brazil, Afghanistan and the Middle East, a local mayor and a visiting millionaire, alongside many languages – Cantonese, Japanese, Portuguese, Hebrew, Arabic, English, and French. Every detail is attended to – the costumes, the masks, the puppets, the props (including simulations of an exploding volcano, a helicopter and a camel) sound, song, music and lighting, all a marvel of detail and beauty. It is spectacle in every sense.

And yet. Seductive as L’Île d’Or is, the theatrical scrap-bag of cultural influences and elements fails to mask the absence of coherent narrative shape and structure. Dream and porosity are frequently used to describe the company’s approach to theatre-making: anything can happen and myriad characters come and go seemingly without consequence. L’Île d’Or is a fantastical dream of action, lacking the disciplined minimalism of its inspirational source, Noh. Does it matter? Not much.

When the finale arrives and the ensemble of 33 actors are gathered on stage for the culminating set piece, a Noh fan dance performed to Vera Lynn’s We’ll Meet Again, the audience is deeply moved, they applaud enthusiastically and, filing past a gracious Mnouchkine, they leave with a sense of hope, of something healed and above all of optimism. “Theatre talks of you and me,” says performer and company member Nirupama Nityanandan. “And of truth, and courage and hope and poetry, and I think all these things we tend to forget in our everyday lives.”

“L’Île d’Or is a humorous declaration of love for Japanese culture,” confirms Mnouchkine in an interview in Télérama with Joëlle Gayot.

It’s a bold move to work within the Noh tradition, at a time when accusations of cultural appropriation and unease surrounding the appeal of the exotic are raw.

Grant refutes this thinking: “The whole basis of theatre is portraying someone else, it’s about being another. When you start chipping away at the list, saying you can be this but not this, but actually, you can only be someone just like you, we’re starting to rewrite what it is to be an actor.”

Mnouchkine has argued that theatre is a human collaboration. Performers may speak a different language, hail from a different country and culture, work in a different theatrical tradition but, at Théâtre du Soleil, it is their humanity that unites them.

Not everyone agrees. When Théâtre du Soleil partnered with the director Robert Lepage in 2018 to present a play Kanata, exploring encounters between the indigenous people and the European in Lepage’s native Canada, the response was vitriolic. It created a sensitive situation. According to Grant, “Our funders pulled out and we were accused of cultural appropriation.”

Undaunted and in spite of it, Mnouchkine staged Kanata at La Cartoucherie, citing the dangers of self-censorship born of a fear of being seen as racist. “Ariane hasn’t shied away from bringing to the theatre these other worlds that inspire her, these other traditions and languages and people who don’t look like us. I think we can continue that because we’re here in France and because this company has the courage to keep doing it,” affirms Grant.

More successful and better received was Le Dernier Caravansérail (2003-

2006) a play about the refugee crisis, where the legendary wars and aftermath described in the Greek classics The Iliad and The Odyssey

chimed with the plight of present-day asylum seekers at Sangatte, Pas de

Calais, attempting Channel crossings in makeshift rafts.

“We had, by chance, 14 new actors for that show,” says Grant. “They had joined the company via what was happening in the world at that time… so we had real refugees, acting refugees, but we would have done it even if they weren’t there.”

As theatres in London struggle to keep going amid funding cuts, staff shortages, cost of living crisis and rail strikes, Théâtre du Soleil in Paris endures. Its shows may not be to everyone’s taste, but its ambition and boldness can’t be denied. Nor its generosity.

Says Grant: “We often talk about the company as a big ship, and there are

little rowing boats following in our wake… they’re young artists or companies we’ve taken under our wing so they can float in their own way.”

L’Île d’Or continues at La Cartoucherie until March 5. More on Theatre Du Soleil at www.theatre-du-soleil.fr

Deborah Nash is a journalist and creative producer. She writes for the FT, The Wire and France Today, among others. Her most recent show is a Japanese Noh play, Sumida River, reinterpreted by Deaf performers in BSL and JSL