Nearly all modern European languages belong to the Indo-European language family, as do most of the languages of Iran, Afghanistan and the northern South Asian subcontinent.

But where did Indo-European come from in the first place? Exactly where the original Proto-Indo-European language was first spoken is an intriguing question and the subject of much discussion. One piece of evidence which linguists have employed in an attempt to locate the original homeland is shared vocabulary. If it can be shown that all or many of the modern Indo-European languages have words in common referring to natural phenomena which are geographically restricted in their distribution, that could provide some strong evidence.

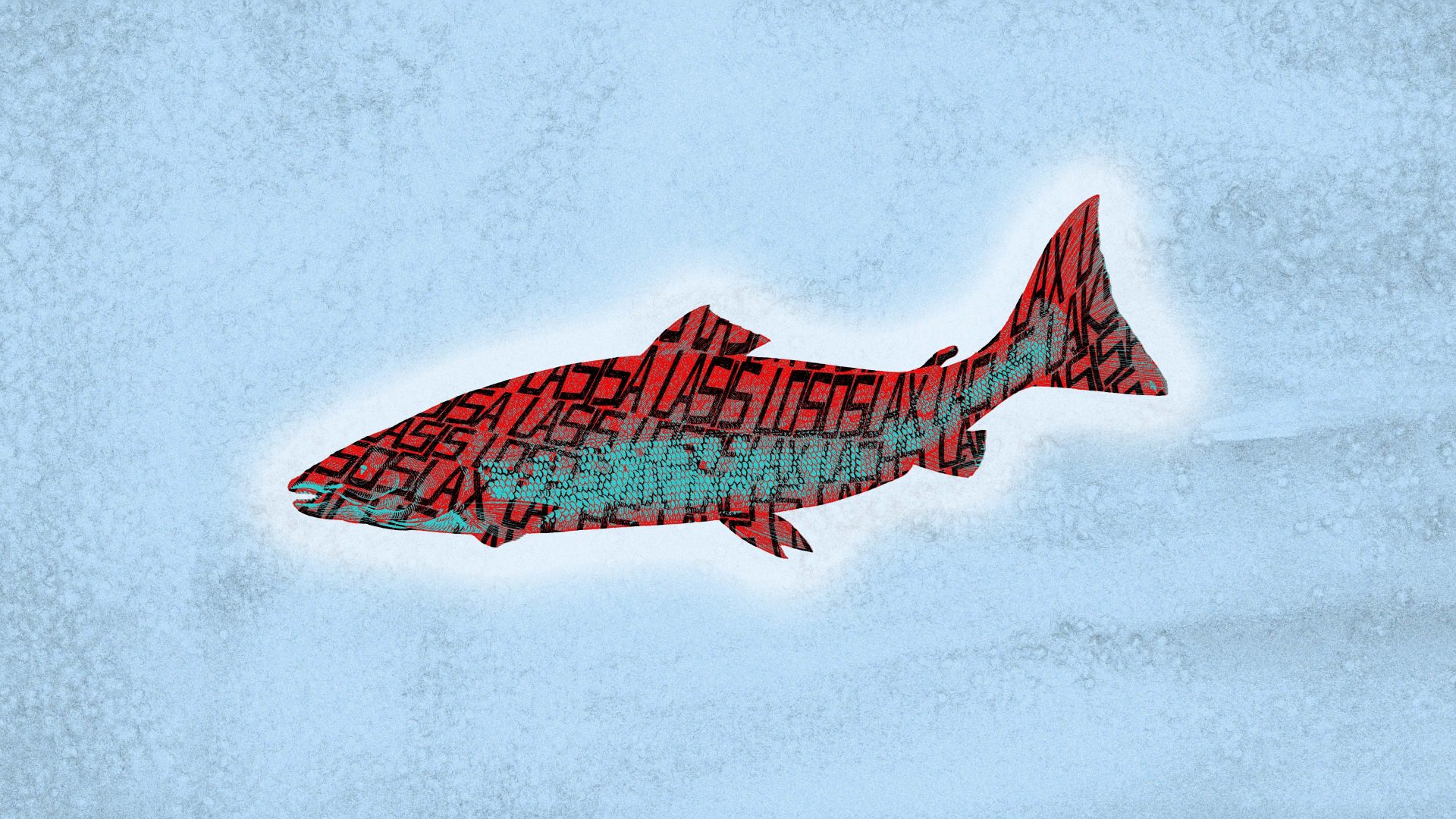

For example, the Germanic, Baltic and Slavic languages all use words descended from the Proto-Indo-European root laks, meaning “Atlantic salmon” (Salmo salar), which suggests that the parent language must have been spoken in the region where these salmon are found, namely North-Central Europe. The modern German word is Lachs; in Icelandic and Scots it is lax; in Norwegian the word is laks, in Lithuanian lašiša, in Latvian lasis, and in Czech and Slovenian losos.

But there is a big problem with this approach: there can be no guarantee that the shared word applies in all cases to the same phenomenon – in this instance, to the same species of fish. A chastening example is provided by the English word robin, which refers to two entirely different species of bird as found respectively in Europe (Erithacus rubecula, a flycatcher); and North America (Turdus migratorius, a thrush): the word is shared but the object it refers to is not.

Another example is the beech tree. Words which are descendants of the parent Indo-European word for beech, bhago, occur in the Romance, Celtic, Slavic, Baltic and Indo-Iranian languages, as well as in Greek and Albanian. Some scholars therefore suggested that the Indo-European Urheimat or homeland must have been located in an area west of a line connecting Kaliningrad and the Black Sea, because this is where beech trees are currently found.

As with Salmo salar, though, we cannot be sure that the word for “beech” is used for the same type of tree in all these languages. There are indications that it has sometimes referred to the elder, the oak, and other species of tree. And for climate-change reasons, we cannot be at all sure that the current geographical distribution of beech trees is the same as it was earlier.

So this initially interesting, shared-vocabulary approach to the homeland question has now mostly been superseded by other philological and archaeological approaches.

Many linguistic scientists today believe that we will probably not be too far wrong if we suppose that the Indo-European homeland was located somewhere in the area between modern eastern Ukraine and western Kazakhstan. This area was the part of the vast Eurasian Steppe which is sometimes known as the Western Steppe, with steppe (originally a Russian word) meaning a relatively level, treeless and mainly grassland plain.

The Western Steppe stretches from the mouth of the River Danube, where it debouches into the Black Sea in the Bulgarian-Romanian borderlands, through Moldova and eastern Ukraine, and then eastwards across the lower Volga regions of Russia and on to western Kazakhstan, passing to the north of the Caucasus mountains.

And, interestingly, it is not the case that beech trees are found over all of this area.

BOOK

One rather widely accepted etymology for the English word book is that it is related to the word beech. This might have come about from the practice of Germanic tribes of using strips of beech wood for scratching or writing symbols on.