Two men, Khalil Islam and Muhammad A Aziz (formerly Thomas 15X Johnson and Norman 3X Butler), had their murder convictions overturned last week. Islam did not live to see his exoneration. Aziz is now 83 years old. Both men spent two decades incarcerated for a crime they did not commit.

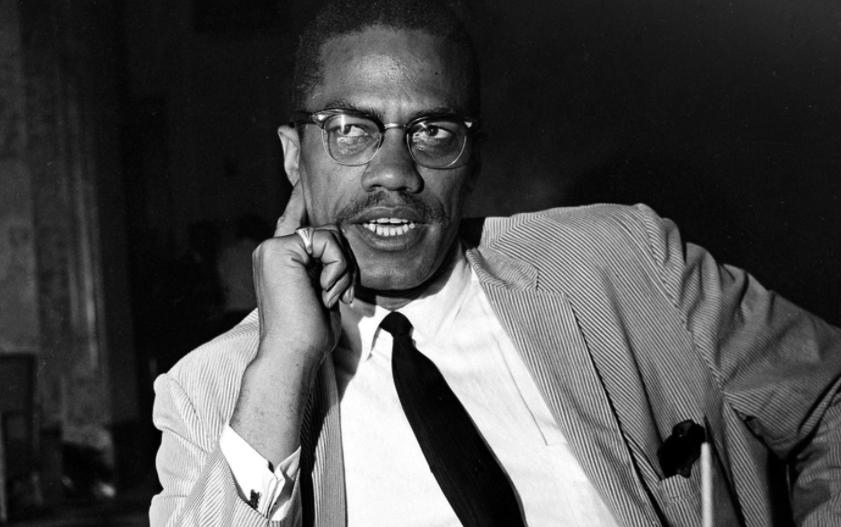

Such injustice is all too common in America. The only noteworthy distinction in this case was the man whom they were accused of killing — Malcolm X. Malcolm X was assassinated in front of a packed audience in New York’s Audubon Ballroom in February 1965. Three gunmen participated in the attack. One assassin, Talmadge X Hayer, was caught at the scene. His accomplices escaped.

The police soon arrested two suspects, Johnson and Butler, despite lacking any physical evidence linking them to the crime or to their co-defendant. Hayer confessed his role, but swore that Butler and Johnson were innocent. Police and prosecutors refused to believe him. Despite having alibis, both men were found guilty of first-degree murder based on flawed witness testimony, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

More than half a century later this perversion of justice has been reversed. But it took a 2020 Netflix documentary miniseries to reignite attention on the case before the wrong was righted. Few people can rely on similar aid.

This week another man was released from prison in Missouri after being confined for 42 years. Kevin Strickland was 18 years old when he was arrested for a triple homicide. He has spent his entire adult life behind bars for a crime he did not commit. Again, there was no physical evidence linking him to the crime. Again, his co-accused pled guilty and insisted that Strickland was innocent. Again, false eyewitness testimony led to his conviction. Again, he received a life sentence.

It took another determined investigation by the Kansas City Star to expose the truth. In September 2020 the Star ran a series that cast doubt on Strickland’s guilt. This prompted local prosecutors to review the evidence, and in April 2021 they declared him “factually innocent”. The only person with authority to release him, Republican Governor Mike Parson, was unmoved. He preferred to let an innocent man rot in prison.

On August 28, 2021 Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker filed for a new evidentiary hearing under a fresh Missouri law designed to address wrongful convictions. Even then Missouri’s Republican Attorney-General Eric Schmitt fought Strickland’s release. Schmitt is running for election to the US Senate in 2022.

Eighteen years old. Imagine spending your entire life locked up for a crime you did not commit. Strickland is now 62 years old. Nothing can return the life stolen from him. His mother died in August, with his potential release still pending. Parson refused permission for Strickland to attend his mother’s funeral. Petty cruelty.

Islam, Aziz and Strickland are among more than 100 prisoners whose convictions have been overturned in 2021. Almost 2900 prisoners have been cleared since DNA evidence first reversed a conviction in 1989. Half of these innocent people were Black, in a country where Black Americans comprise 13% of the population. 133 exonerees were death row inmates.

The data suggest these 2900 are the tip of the iceberg. Exonerations can take thousands of hours of work over many years by investigators and lawyers, most working pro bono. They typically focus on violent crimes. Lesser crimes receive scant attention from anyone.

Estimates of wrongful convictions across the United States range from 2% to 10% of cases. There are 2.1 million people in prison in America, the highest total of any country. That means anywhere from 40,000 to 200,000 prisoners should not be there. Most will never receive justice.

To grasp how a system can get it wrong so often, it’s necessary to understand that most defendants never receive a fair trial. There simply aren’t enough people, facilities, time and money to allow that. More than 96% of cases are resolved by plea bargain. This means the accused admits their guilt, typically in return for reduced charges, sentencing leniency, or other negotiated concessions.

That sounds reasonable until we consider the power mismatch. Eight in 10 defendants can’t afford a lawyer. Public defenders are routinely underfunded, and can be assigned caseloads of more than 100 clients at a time. Most people charged never receive proper representation. Without effective counsel, they are at the mercy of police and prosecutors already convinced of their guilt.

Any system is only as reliable as its weakest links. Experience has shown that while most people who enforce the law do their best to be fair and impartial, none is immune to society’s cultural and systemic biases. That’s not possible. This dilemma is compounded when those in authority bend or break rules because they are determined to catch a crook.

The Supreme Court has ruled that police can lie to suspects. Exculpatory evidence is sometimes withheld or “lost”. Bad forensics can get treated as scientific gospel. Eyewitnesses are often wrong. Favours and deals contribute to unreliable testimony or outright perjury. Alibis are disbelieved or ignored. False confessions are all too common, derived from promises, threats, and other coercion tactics.

When police and prosecutors commit violations, they almost never suffer any consequences. Qualified immunity protects them from personal liability. Police unions back their members, and prosecutors rarely face sanctions. In many instances, the wrongdoers steadfastly defend their actions and view efforts to hold them accountable as unjust. Lack of accountability provides little incentive for reform.

John Grisham, bestselling author of legal thrillers The Firm and The Pelican Brief, worked as a criminal defence lawyer for a decade before he switched to writing as his day job. He also served in Mississippi’s state House of Representatives. Today he sits on the board of the Innocence Project. He argued recently for five reforms that would help redress the rate of wrongful convictions:

1. Abolish, or strictly monitor, the testimony of jailhouse snitches;

2. Video the police during interrogations and prohibit the use of deception;

3. Require expert testimony to be based on established science;

4. Establish fair guidelines for police line-ups and identifications; and

5. Remove the broad immunities that police and prosecutors enjoy, and hold them accountable when they engage in misconduct.

We are told from childhood that the bedrock principle of justice is the assumption that we are innocent until proven guilty. It should shock our consciences that this isn’t true. But we barely notice. We defer to police and prosecutors because they keep us safe, and we want to believe them. We give them the benefit of the doubt. Our law-and-order, tough-on-crime politicians encourage this fealty.

There is nothing tough or lawful about locking up innocent people. The true reason we don’t care to fix the system is that we don’t think it could ever happen to us. Our empathy evaporates because we can’t imagine ourselves in their shoes.

We inflict a double injustice upon crime victims and society when we incarcerate the innocent. While law enforcers congratulate themselves, the real criminals remain free and unpunished. Many offend again, exacerbating the original failure.

We should heed a lesson from Ronald Reagan: trust but verify. We should trust our public officials to do right. And we should encourage that trust by ensuring that they do.

This article first appeared on Crikey.com.au with whom The New European has a content-sharing agreement