For much of 1971, the most popular film in the UK, US and a good many other places was Love Story, a wholesome, nay, winsome, romance now largely forgotten now except for its tag-line “Love means never having to say you’re sorry”.

But as the year wore on, a very different sort of film began to dominate. The autumn and winter of 1971 saw the release of a succession of films that would provoke outrage wherever they played, films that their detractors claimed revelled in sex, violence and sexual violence. And their creators were not ready to say sorry, either.

The controversies surrounding them have not been resolved by time. Reflecting on their golden anniversary, it is easy to understand why contemporary critics were so shocked – because some of them remain deeply shocking still.

Straw Dogs was made by the already notorious Sam Peckinpah, and lived up/ down to his reputation, while Ken Russell’s The Devils mixed-sex, violence and religion in one censor-bothering package. Meanwhile, A Clockwork Orange caused such a palaver it became part of British film folklore. Straw Dogs was released early in November 1971 to an immediate outcry. Peckinpah was used to that. He’d got his start in Westerns, first on TV then in features, becoming famous for The Wild Bunch, which he made in 1969. Taking advantage of the collapse of censorship, “Bloody Sam” used bullet impacts to paint the screen red.

He was to do worse. Straw Dogs took him from the Wild West to our own West Country; it’s set in picture-postcard Cornwall, although Cornish tourist chiefs would take a dim view of it. Peckinpah had not left his violence at home: virtually the first shot is of a mantrap.

It’s not fair see Peckinpah as just a gorehound, though. His innovation was not so much the depiction of violence but showing that violence could be a subject or a theme to be explored, both its prevalence and attraction. He shook up the tidy morality that earlier American films had developed to justify any shooting or killing, especially in the Western. Old-timey cowboy films made violence look easy; ex-soldier Peckinpah knew it wasn’t.

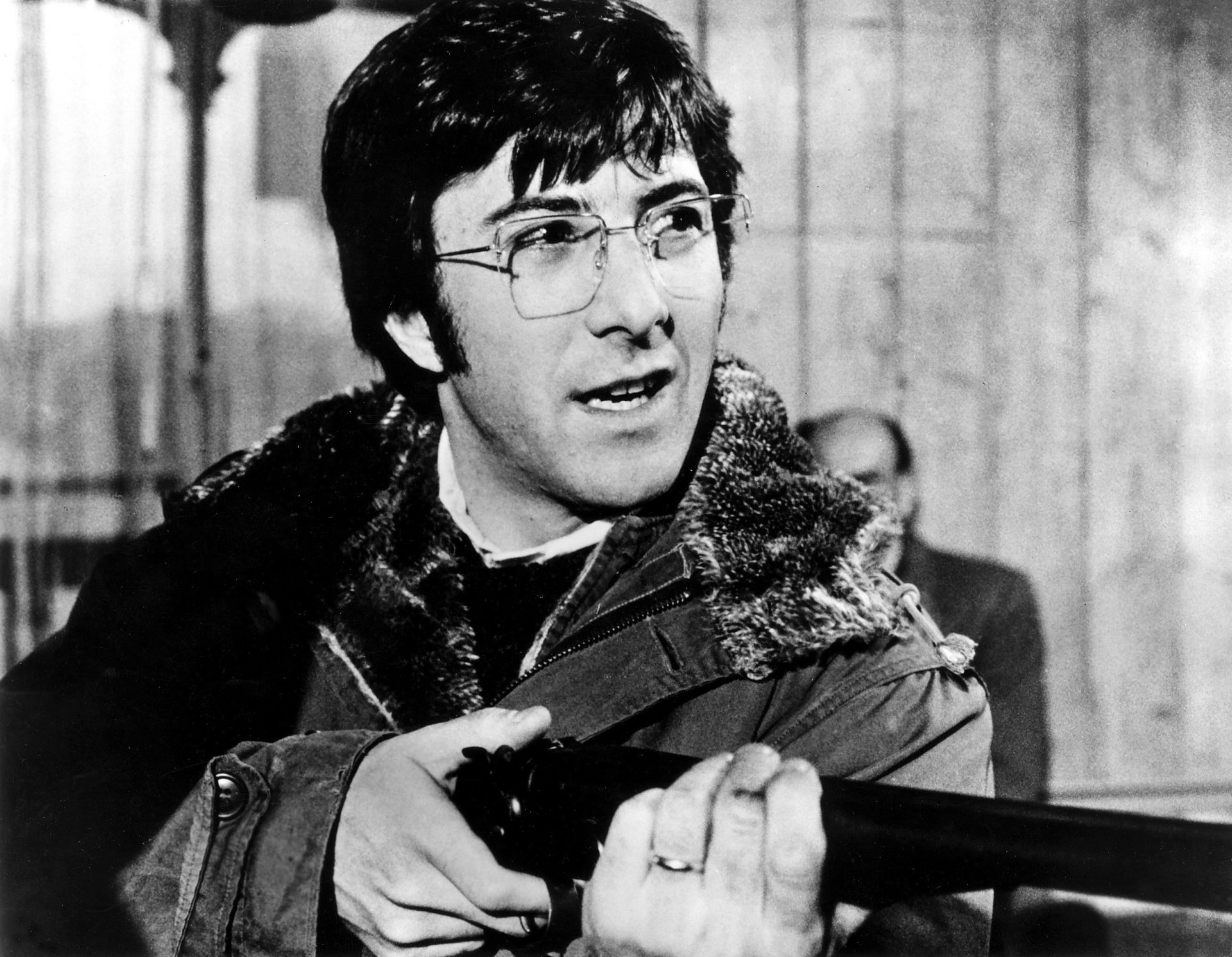

He also knew how close to the surface violence was, even in people who might seldom raise their voice in anger. Straw Dogs concerns an American mathematician, David, (Dustin Hoffman) who returns with his younger English wife Amy (Susan George) to the Cornish village where she grew up. In time, a situation arises that obliges him to use force (and his trusty mantrap) to protect his home from local roughnecks, something he takes to with disturbing ease, and even – possibly – enjoyment.

The setting isn’t incongruous but essential: anyone who dreams of escaping the terror of the city in the countryside is in for a rude surprise. Violence lurks just as surely in quaint rural England as it does anywhere else, a part of nature.

The real controversy though is the sequence where Amy is raped. Contrary to what is sometimes said, it is not staged to suggest she “enjoys” it; this is not meant to be an easy scene to watch. But it is attenuated and arguably extraneous. There have been impassioned defences of the film over the years, including from feminists, but many regard it as misogyny writ large: far more than any other film mentioned herein, Straw Dogs has never quite been tamed.

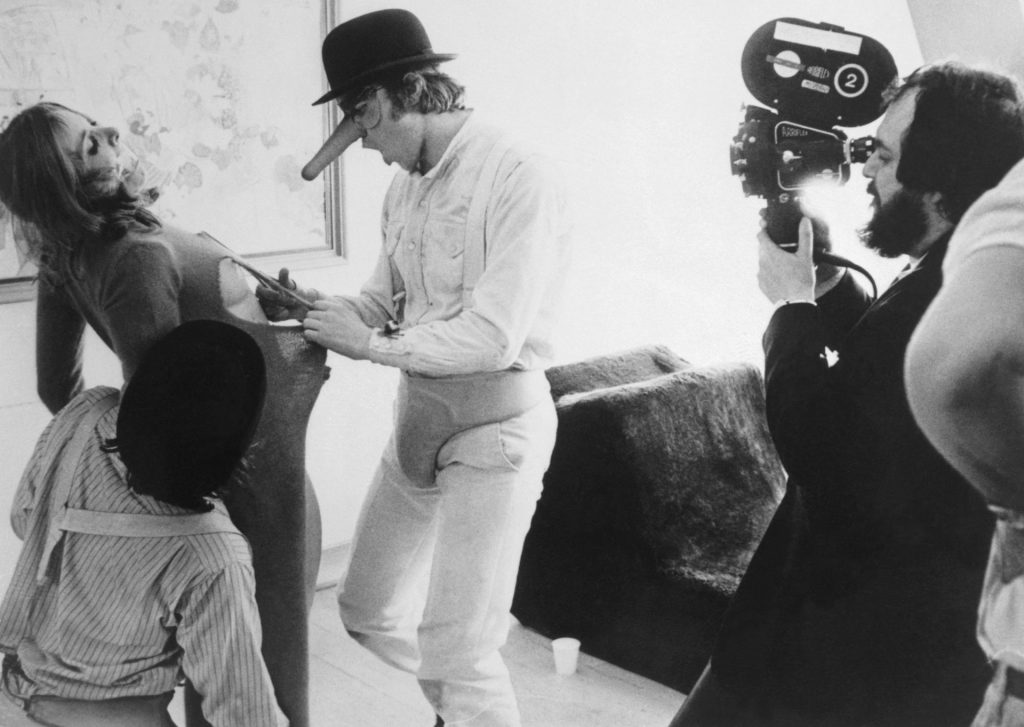

It set the scene for a further flare-up. The posters for A Clockwork Orange described it as being the adventures of a young man whose principal interests are rape, ultraviolence and Beethoven, and – “oh my droogs” – the film delivered on that promise.

Stanley Kubrick’s film was first among equals in this cavalcade of controversy. It caught the mood of the times, especially in Britain; the Swinging Sixties were over and any residual optimism had evaporated. Instead, it was a time of civic decay, official incompetence and a seeming epidemic of violence.

All those are to be found in Kubrick’s adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ novel. For the first half, we follow our teenage hero Alex (Malcolm McDowell) and his pals as they amuse themselves with assorted acts of thuggery. Some people said it glamorised violence and they’re not entirely wrong, for no matter how awfully he behaves, Alex remains cool and cocky.

The second half turns the tables on him, as he becomes a victim, tortured by the state and then let out into a cruel world as a reformed character who can’t defend himself. Burgess claimed his novel was a parable of free will; Kubrick’s approach was different. Like Peckinpah, he was intrigued by the darker sides of human behaviour, and how easily it could be invoked. (Indeed, perhaps too intrigued: McDowell essentially went through the same torments as his character. Shooting one scene required his eyes to be clamped open: “When we shot it, the lid-locks kept sliding off my eyelids and scratching my cornea. When the anaesthetic wore off, I was in such pain I was banging my head against a wall… Stanley was mainly concerned about when he would be able to get his next shot.”)

The trouble is, not everyone locked on to Kubrick’s philosophical musings. Soon after the film was released in Britain, there were reports of kids wearing the bowler hat/ white boiler suit/ heavy boot outfit favoured by the droogs. Furthermore, some of them were apparently committing acts of violence. The tabloids scented blood; Kubrick’s ultimate reaction was to withdraw the film from circulation in the UK for the rest of his life.

When it was re-released after his death in 1999, there were no reports of any copycat violence. Instead, we could see what a very good film it is, perceptive about young British men’s attraction to violence and, indeed, how violence is depicted on screen. But then, the tabloids had other targets by then.

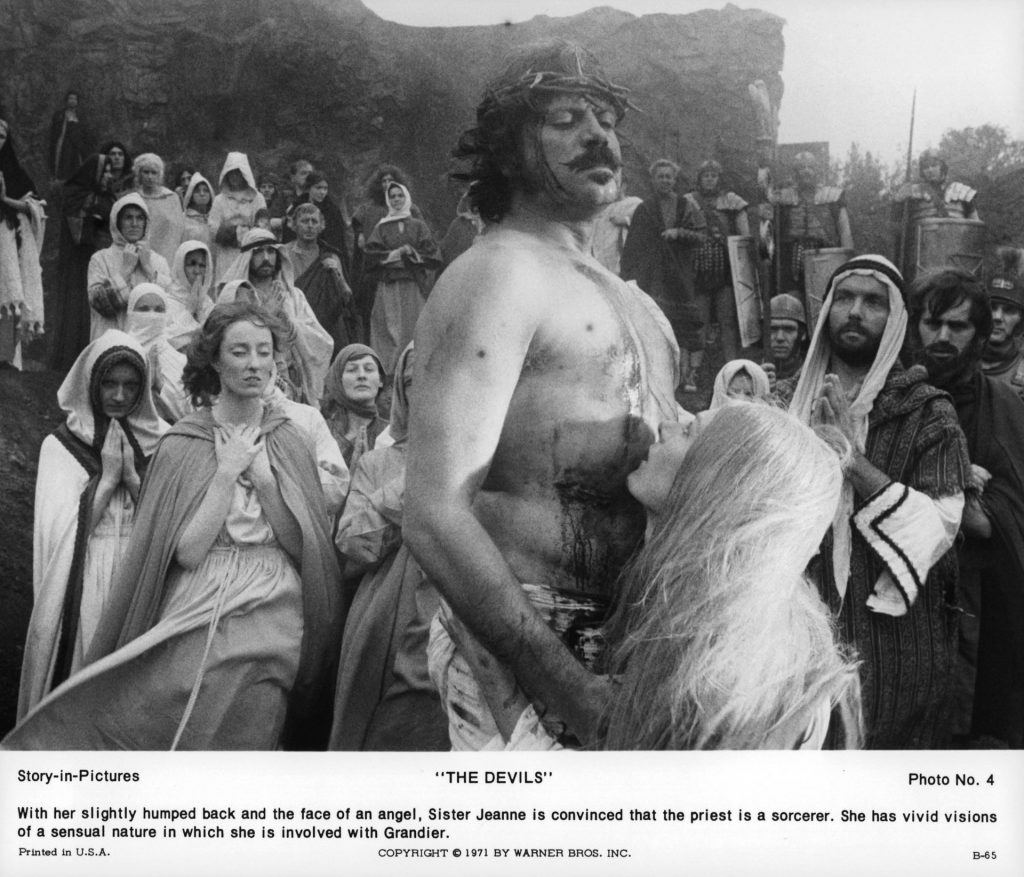

Russell’s The Devils had opened earlier in the year, but the slower distribution patterns of 1971 meant it was still winding its way through the provinces when Straw Dogs and A Clockwork Orange opened. The Devils derives from Aldous Huxley’s The Devils of Loudun, itself based on a real incident in which the secular authorities of France used an outbreak of demonic possession in a convent as a means of furthering their own political power. Russell was then a practising Catholic and resented any charges that the film was blasphemous. “It’s about the degradation of religious principles,” he once said. “And a sinner who becomes a saint.” It is an attack on power, not Christianity: its targets are the hypocrisies and humbug of those in authority, whether spiritual or temporal.

The trouble is, Russell was something of a stranger to conventional good taste. It is a film of hysterical excess: the “demonic possession” is framed as a case of good old-fashioned sexual repression, brought to the boil by brooding man of the cloth Oliver Reed, whose saturnine good looks send the sisters doolally. The possessed nuns gambol around in the nip while the torturers do their work with particular relish. For many it was all much too much: after all, one man’s “hysterical excess” is another’s pornography.

At least part of the controversy – with The Devils, with all these films – was a straightforward culture clash. Film was changing. The 1960s had brought forth a series of New Waves across Europe and in the 1970s, it was clear another evolution was happening. In Germany, Rainer Werner Fassbinder was establishing himself as cinema’s latest enfant terrible with things like Whity and Beware of a Holy Whore, while Pier Paolo Pasolini wound up the Vatican – and had the biggest hit of his career – with The Decameron, a film whose licentiousness would have been simply unimaginable even a couple of years before.

Another consequence of the collapse of censorship was the opportunity to tell more complicated, grown-up, stories and filmmakers were taking advantage, such as Louis Malle and his Murmur of the Heart (aka Dearest Love). Art films were even becoming big business: Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice had Hollywood production values and was a sizeable hit.

Ever-keen on profit, American studios were taking note. The returns from their own more radical fare such as Bonnie and Clyde suggested that here was a way of capturing that all-important youth market. It was in that climate that something like The Devils could get the green light from a major studio.

Rather less thought was given to how regular folk might react. The same screen where people had taken the kids to see The Jungle Book was now showing what seemed to be celebrations of pure depravity, a change that seemed to happen in only a few weeks. Mainstream audiences still expected movies to look like Love Story, because that’s what the mainstream looked like still.

Not all this new wave was controversial. Released in the UK in late October 1971, The French Connection grabbed the traditional cop movie by the scruff of its neck and yanked it up to date. But although it might have looked new and dangerous – the poster showed a cop shooting someone in the back, one of the great taboos of Westerns – there was nothing in the film that might genuinely unsettle anyone. A rather more contentious cop movie came later in the year, only it wasn’t mainstream audiences complaining. Released in the US two days before Christmas, Dirty Harry was a four-square action film, with none of the ‘realism’ of The French Connection, and one that would influence the genre in perpetuity.

It was a film that appalled sophisticated, liberal critics. Pauline Kael, then the doyen of such people, was especially incensed: “A rightwing fantasy… fascist medievalism… deeply immoral.”

But director Don Siegel was a more subtle filmmaker than she realised. If the titular Harry Callahan (Clint Eastwood) is a hero, then it’s only because everyone else, especially sniper/kidnapper/ extortionist targeting random civilians Scorpio is much worse.

For Kael the film’s huge success proved their point: this was president Nixon’s “silent majority” cheering on police brutality. There’s a degree of snobbery in that view that should make us uncomfortable, but can it be denied that at least some (even most?) viewers would have taken Dirty Harry as simple wish-fulfilment? If someone as savvy as Kael could miss the point of Dirty Harry, then surely average punters might have done so too. Goodness knows, enough people did with A Clockwork Orange, Straw Dogs and The Devils.

The class of late 1971 remain ‘problematic’. If violence has become more commonplace in movies now, the sexual politics have become more noticeable, and objectionable.

All the films mentioned here were directed by men – men, moreover, who had not even begun to consider the impact (or necessity) of feminism. Yet for all their flaws and infamy, all these films are profoundly serious, significant and often excellent; even Straw Dogs cannot easily be ignored. It, and its controversial colleagues remain shocking because they’re so intelligent and acute.

They are films any cinephile ought to watch and not for their notoriety: the controversies are the least interesting things about them.