It may have been overshadowed by Everything Everywhere All At Once at the Academy Awards, but four Oscars is some going for any film – let alone one in German, adapted from a book published almost a century ago. Edward Berger’s All Quiet on the Western Front had already scooped seven Baftas, including best picture, before adding golden stauettes for best international feature, cinematography, original score and production design to its already crammed mantelpiece.

Commissioned by Netflix, Berger’s is the third screen adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 novel Im Westen nichts Neues, literally “nothing new in the west”, and the first to be made in German. For all its awards and plaudits, however, the film has come in for a significant degree of criticism – notably in Germany, where portrayals of war come with more baggage than anywhere else – for two broad reasons.

Some have questioned the advisability of releasing a film in which an invading force is portrayed sympathetically when we are a year into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to some critics apparently under the impression that it’s a western pitching black hats against white hats, the film presents an overly sympathetic portrayal of the Germans while casting the French as ruthless killing machines. As Nicholas Barber put it in a Guardian column last week, “all too often [Berger’s] All Quiet on the Western Front depicts the Germans as the good guys, while the French are cruel and spiteful villains”.

This rather seems to miss the point. The film, like the book, isn’t about apportioning blame or appointing heroes and villains, it’s about the dehumanising experience of fighting on the Western Front and the sheer pointlessness of the loss of life in unimaginable numbers under unimaginable conditions. To the German characters in the film, through whose eyes we are experiencing the final acts of the war in visceral detail, the French were ruthless killing machines, a faceless enemy propagandised from the schoolroom to the training camp into monsters.

It’s only when the protagonist, Paul Bäumer, in one of the film’s most affecting scenes, murders a French soldier with whom he finds himself alone in a shell hole and is forced to listen to his slow, gurgling demise that he realises the man next to him is just another human being trying to get through the conflict and get home. Bäumer’s apologies and promise to send the soldier’s paybook back to his family seem all the more pathetic, the pointless epiphany of a young man whose own hopes and dreams have been destroyed among the blood, mud, rats and lice of the trenches.

“I have killed Gérard Duval, the printer,” says Bäumer in the novel after leafing through the Frenchman’s papers. “I think wildly that I shall have to become a printer, become a printer, a printer –”.

That the soldiers in All Quiet on the Western Front are German adds to the impact of the film, a sobering about-turn on the usual cinematic war fodder we are customarily fed. The colour of the uniforms is irrelevant, this is about humanity and how trench warfare deprived combatants of almost every shred of what made them human. Their entire world, everything they knew, was reduced to raw survival in a few yards of muddy ground on the Franco-Belgian border.

“We learned that a polished tunic button is more important than a set of philosophy books,” says Bäumer. “We came to realise – first with astonishment, then bitterness, and finally with indifference – that intellect apparently wasn’t the most important thing, it was the kit-brush; not ideas, but the system; not freedom, but drill.”

Criticising the film for portraying ordinary German soldiers as anything other than psychotic murderous bigots is like criticising the Christmas Truce, when allied and German soldiers on the Western Front met in No-Man’s Land to exchange cigarettes and chocolate, and staged a full-scale football match without anyone bayoneting anyone else. That came later, when they had to go back to their lines and stop being human again.

The second criticism of the film is more plausible, albeit still debatable. In Germany, Berger’s adaptation has come under fire for playing too fast and loose with Remarque’s original novel. Of all three screen adaptations, Berger’s strays farthest from the book, adding scenes, characters and the entire narrative thread of the Armistice signing in a railway carriage in the forest of Compiègne while leaving out many aspects of an already slim novel.

Filmmakers have always viewed source texts as launchpads rather than binding scene-by-scene shooting guides. Novels and films are entirely different mediums, with their own rhythms and pacing, so a faithful adherence would only produce a strange – and very long – cinematic experience.

When that source text is All Quiet on the Western Front, however, problems arise because so many Germans hold that novel dear. As one of the biggest-selling works of fiction of all time in Germany, one that strikes at the core of modern German-ness, changing the narrative is a risky undertaking.

Berger defends his interpretation by quoting Remarque himself, who said of the 1930 American film adaptation, “a book is a book and when it’s made into a film it’s a new medium”, but should All Quiet on the Western Front sweep the board at the Oscars it wouldn’t be any kind of vindication as far as his critics are concerned.

Remarque’s book has always been on the right side of history. Based on his own experiences and those of men he knew at the front, when it was published in 1929 it preserved the experiences of a generation of young men “destroyed by war, even though it might have escaped its shells”. The first great novel of the first world war in any language, the book sought to carve through the sanitised patriotism controlling the postwar narrative with an honest depiction of the psychological damage caused to those who came home after living through unspeakable horrors.

Although it sold 1.5m copies in Germany in its first year alone, it soon had noisy critics. Older conservatives and the fledgling fascist movement, keen to play up the narrative that Germany had been deliberately humiliated by the terms of the Armistice and the Treaty of Versailles, condemned the book as treacherous, an insult to the brave men who had fought and died at the front.

Meanwhile, an English translation sold 600,000 copies in Britain in its first year and a US edition shifted 200,000, albeit in a watered-down version because some of the more graphic incidents and language were considered, according to its publisher, “too distinctly Elizabethan, too much of the old free-and-easy Anglo-Saxon order” for the American market.

Remarque had been working as a sports journalist for a Berlin newspaper when the book was published after a peripatetic postwar career that included stints as a racing driver, teacher and copywriter for a Hanover tyre company. The more he struggled to adapt to civilian life, the more important he felt it was that his experiences and those of men like him should challenge the prevailing narrative in his defeated nation. He wasn’t hearing those stories, so he would have to write them himself.

Conscripted in 1916, Remarque was wounded five times, the last so badly he was in hospital for almost a year before being sent back to the front in October 1918 when Germany’s losses were so great that practically anyone upright was forced to go. It was during his convalescence that Remarque began noting down the stories and experiences of other wounded men, lending All Quiet on the Western Front a polyphonic truth in the guise of a novel.

The success of the book, and the celebrity it accorded him (even the nameplate on his Berlin doorbell was stolen by souvenir hunters) took Remarque by surprise, but he welcomed the opportunity to become a full-time novelist. Nothing he wrote would ever come close to the success of his debut and certainly nothing he wrote had a comparable impact – positive or negative – on his life.

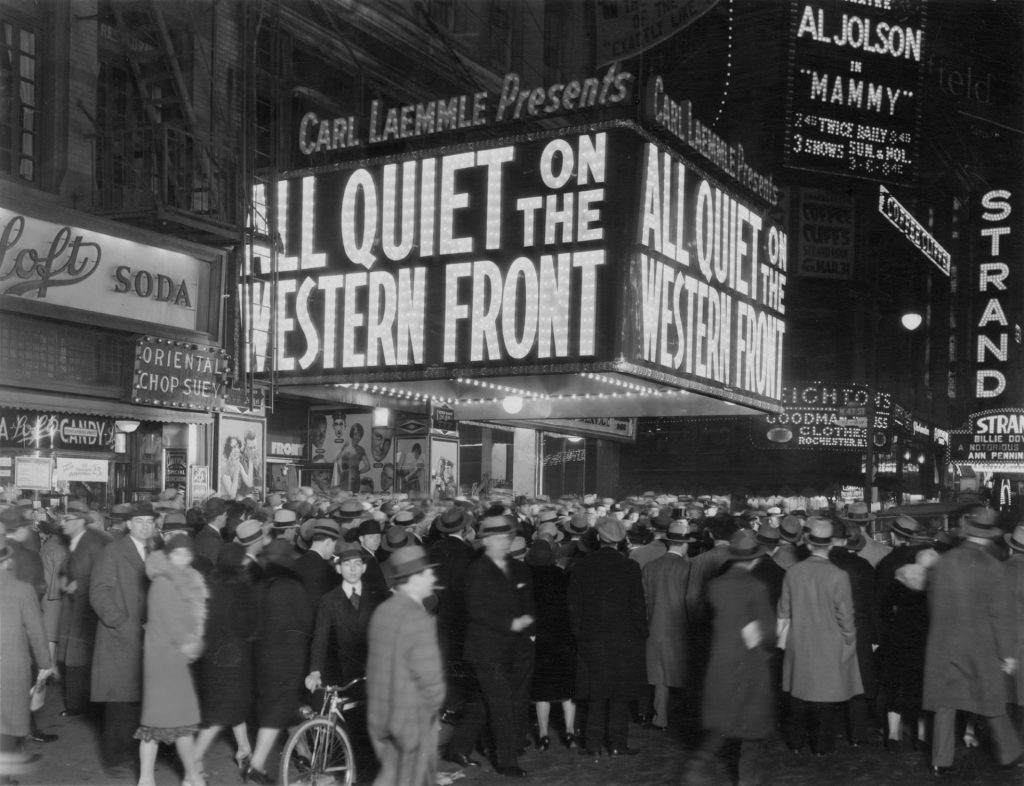

The American film producer Carl Laemmle optioned the book almost immediately, and the screen adaptation directed by Lewis Milestone appeared in 1930. It was an overnight success: only The Jazz Singer, released the previous year, outperformed it at the box office.

Predating the Hays Code, the film’s graphic nature was shocking for the time and remains so: in one of the first battle scenes an advancing soldier falls and grabs some barbed wire with both hands. There’s an explosion, the smoke clears, the soldier has vanished but there are still two dismembered hands hanging from the wire.

The film’s final scene departs from the book to become one of the most famous and poignant moments of early cinema. As the clock ticks down to the Armistice, Bäumer spots a butterfly just outside the trench. Having been deprived of such beauty for so long he is captivated and leans out to hold the creature. The camera lingers on his hand and forearm when a shot rings out, the arm stiffens briefly, and goes limp.

It’s a little different from the 1979 made-for-television version in which Bäumer is killed while sketching a songbird, and certainly from the current version, where he is run through from behind with a bayonet during a raid on an enemy trench ordered by a mad general seconds before the Armistice comes into effect.

When Milestone’s film was released in Germany it caused an even greater furore than the book. Riots in Berlin orchestrated by Nazi brownshirts greeted the opening night on December 5 1930, and the screening at the Mozarthalle the following evening saw Joseph Goebbels lead 150 brownshirts into the auditorium to disrupt the showing with stink bombs and mice, and spittle-flecked antisemitic abuse hurled at the screen.

Remarque’s honest, unflinching portrayal of the war experience was anathema to the Nazi myth that the German army had been nothing less than a proud, disciplined fighting force for a nation ultimately betrayed by weak-willed politicians and, naturally, the Jews.

The night before Hitler was appointed chancellor in January 1933, Remarque, who had watched the rise of the Nazis with increasing horror, decided to drive to his house in Switzerland, a decision that arguably saved his life. On May 10 his books were among those burned on Berlin’s Bebelplatz, and later that year it became a criminal offence to possess a copy of All Quiet on the Western Front.

In 1943, Remarque’s sister, Elfriede, was convicted of being “a dishonourable subversive propagandist for our enemies” and guillotined. The notorious Nazi judge Roland Freisler told her as he passed sentence, “Your brother is unfortunately beyond our reach. You, however, will not escape us.”

By then, Remarque was in the US – where he was feted by Hollywood and had relationships with Hedy Lamarr, Dolores Del Río, Marlene Dietrich and Paulette Goddard, whom he married. He spent the rest of his life moving between California and Switzerland, rarely returning to Germany.

In light of the book’s turbulent history it’s easy to see why German audiences might object to Berger’s liberal screen adaptation. For all its veering from the text, however, the story remains incontrovertibly Remarque’s in a film perfectly suited to the modern world. Indeed, the Oscars ceremony bridged the extremes of the hell of the trenches and the glamour of Hollywood in the same way as Remarque managed himself.

Hopefully it will also help to perpetuate the memory of the soldiers who fought in those trenches, the young men whose hopes, dreams and futures were stolen, who came alive when letters arrived from home, who forged intense friendships in the knowledge that one bullet could end them, who counted the days until their next leave, who played chess, sang songs and swapped jokes, who burned lice out of their tunics with candles, who moaned about the gristly meat dished into their mess tins, dreamed of a hot bath and looked longingly at the pretty local girls.

Whatever uniform they wore, whichever side they were on, they were innocents thrust into a hellish world far removed from civilisation for reasons most of them didn’t understand. Even those who came back left the best of themselves behind in that cloying, shell-blasted sea of mud that stretched almost the length of a continent. Berger’s film, like Remarque’s novel, keeps their memory alive.